The following lines are intended to make a small contribution to the history of Egypt's First Intermediate Period. Therefore, they are dedicated to the honoured jubilarian, whose treatment of the inscriptions of the alabaster quarries of Hanub (“Hatnub”) taken up by G. Möller still today forms a valuable basis for the exploration of this dark section of history. Here we shall once again examine what we really know about the so-called Herakleopolitans, i.e. the kings of the Ninth and Tenth dynasties of Manetho, and we shall try to prove the uncertainty, even untenability, of some theses which today are almost generally regarded as facts. To the negative statement that we know even less about this time than is usually assumed, unfortunately only few positive results can be added, but it should not be completely unnecessary to separate the facts from the only suspected.

The two dynasties of Manetho (9 and 10), which are said to have consisted of 19 kings each,[*] correspond in the Turin royal papyrus to only one dynasty of 18 rulers (column IV row 18 to column V row 9; summation in V 10).[*] W. Schenkel has shown in his “Fruhmittelägyptischen Studien” (Bonn 1962, p. 141-145) with convincing arguments that historically only one dynasty[*] of Heracleopolis could have existed. In the case of Manetho, the doubling might be due to a later corruption (perhaps only in the tradition of the epitomes). It is therefore advisable to refrain from any attempt to separate the Heracleopolites into two successive rows of rulers and – in order to maintain the conventional numbering – to simply call them a “Ninth/Tenth dynasty”.

To confirm Manetho's (not easily trustworthy) statement that these kings came from or resided in the city of Heracleopolis[*] at the entrance to the Fayum, we have only a few passages. In the biographical inscriptions in the tombs of the contemporary princes ẖty I (Tomb V, line 24), jtj.f-jb(.j) (Tomb III, line 36) and ẖty II (Tomb IV, lines 6 and 11) at Asyut, the city is occasionally referred to as the capital. In the “Teachings for King Merikare”[*] it is mentioned only once in a not quite clear context.[*] In the tale of the “eloquent peasant” Heracleopolis is actually only described as the official residence of the head of the estate rnsj, while the blessed king nb-kꜢw-rꜤ could theoretically have resided elsewhere.

An unsolved problem, which should not concern us here, however, is still the question of the duration of the Herakleopolitan rule and thus of the First Intermediate Period. Manetho's numbers are of course unusable[*] and in Turin's royal papyrus, unfortunately, all numbers are lost here. We know that the 9th/10th dynasty was almost a whole century long (2134-2047/2032 BC) with the Theban Eleventh Dynasty at the same time. On the other hand, the views on the beginning date of the Hercules' period still differ widely. While some still adhere to Eduard Meyer's date 2242 (2233),[*] which was based on an erroneous reading and interpretation of a number of the Royal papyrus already improved by Farina's reworking (Il Papiro dei Re restaurato, 1938), more recent works prefer much later approaches that precede the beginning of the Eleventh Dynasty only by a few decades[*] or coincide with it in time.[*] In all probability, most of the 18 Herakleopolitan kings, who did not leave any traces, sat on the throne for only a very short time, similar to the kings of the Eighth dynasty, so that the entire dynasty could hardly have existed for much more than a century.

First of all, those kings of Heracleopolis (not it chronological order) who are known to us by contemporary evidence shall be listed and discussed here.

1. Horus Mry-jb-tꜢwj King Mry-jb-rꜤ Khety (ẖty). His name stands a) on a copper utensil from Mer[*] b) on an ebony stick of the same origin[*] and c) on the fragment of an ivory box from Lisht.[*] This king is generally, but without compelling reason, equated with the founder of the Herakleopolitan dynasty, whose name was destroyed in the Royal Papyrus (IV 18) and which Manetho calls Άχ&οης (var. Άχ&ωης, armenian Okhthovis). In the “Teachings of King Merikare” (E. 142-143) the dynasty is called the “House of Khety” (pr-ẖty) and also by its Theban opponents.[*] It can therefore be assumed that the name of the founder of the dynasty was indeed Khety, but we neither know his throne name nor do we know whether the mention of an older king mr...-rꜤ in “Merikare” (E. 73-74) refers to him.[*]

2. King nb-kꜢw-rꜤ Khety, whose name is written on a jasper weight which Petrie found at part er-Rataba in Wadi Tummilat.[*] It is about the ruler, in whose government the events are dated, which serve as reproach of the history of the “eloquent farmer”.[*]

3. The best known king of Heracleopolis is Merikare (mry-kꜢ-rꜤ). We know him above all from the famous “Techings of King Merikare”, a propagandistic literary work which, at least in its core, must have originated under his reign,[*] but which is attributed to his royal father, whose name is unfortunately lost in the manuscript. In contemporary testimonies for Merikare we have a) his mention as reigning king and overlord of the prince ẖty II of Asyut in his tomb inscription[*] and b) a small wooden tablet with his name[*] which was found in Mer together with the already mentioned objects which bore the name of mry-jb-rꜤ Khety (note the similarity of the throne name!). Different persons, who lived at the time of the Middle Kingdom and were buried in Saqqara on the cemetery at the Teti pyramid, exercised priestly functions according to their titles at a pyramid wꜢḏ-jswt-mry-kꜢ-rꜤ, whose cult existed at that time.[*] In part they also served in the cult of the similarly named pyramid ḏd-jswt-ttj. From this one has probably rightly concluded that King Merikare' must have built himself a pyramid—however small it may be—in the immediate vicinity of that of Teti.

4. On a stele of the Twelfth Dynasty discovered near Chatana in the eastern delta,[*] next to a sanctuary of Ammenemes I, which could also be found archaeologically in the meantime,[*] a similar one of Khety[*] is mentioned as situated at the same place.[*] This can probably only be a king - the stele have neither this name nor that of the Ammenemes in a cartouche. According to his name he probably belonged to the 9th/10th dynasty; he may be identical with one of the Khety already mentioned or another ruler of the same name of this dynasty. It is interesting that a Herakleopolit appears at this place next to Ammenemes I, the builder of the “walls of the ruler” (Sinuhe B. 16-17; Neferti Ε 33-34). One is reminded immediately of the admonitions “Merikare” E. 88-89 to protect the East against the Asians, as well as of the fact that the name of the king nb-kAw-rꜤ Khety just appears in Wadi Tummilat.

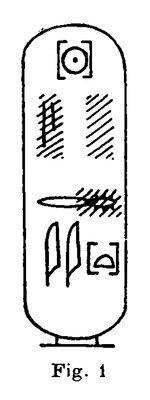

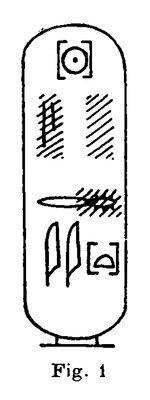

5. Another king Khety - if he is not identical to one of the already discussed - is perhaps named by the inscription no. X in Hanub.[*] Right half of the vertical cartouche is destroyed there; the position of the preserved signs and remains of the signs makes the addition shown here (Fig. 1) possible (throne and birth name in a cartouche).

6. The king in the Hanub inscription no. IX[*] probably also belongs to the Heracleopolites. However, neither the reading of the name[*] nor the chronological position of these rulers[*] can be regarded as certain.

7. Finally, a king wꜢḥ-kꜢ-rꜤ Khety must be treated here, who certainly belongs to the 9th/10th dynasty, but of whom we do not have a contemporary testimony. His name appears several times in the coffin texts of a certain nfrj from Der el-Berscha.[*] From this it was concluded that the king himself had been buried there and that nfrj had appropriated the coffin after the looting of the king's tomb.[*] However, the coffin is certainly of a later date[*] and not usurped. As G. Posener has emphasized,[*] no traces of erased cartouches can be seen in the places of the text where the name of nfrj is written. The simplest explanation for the occurrence of the cartouches in the coffin text of a private person from the province might therefore be that the scribe has thoughtlessly copied a papyrus with the Book of the Dead written for a former king.[*]

WꜢḥ-kꜢ-rꜤ Khety, which is nowhere else documented, is now almost generally equated with the father of Merikare, whose name is lost in the “teachings”.[*] It might be time to say that this equation is completely unprovable. The name of the king cannot be deduced from the text of the “teachings”; the mention of the pr-ẖty in E. 42-43 clearly refers to the dynasty named after its founder, not to a single ruler. The dating and chronological order of the graffiti at Hanub is too uncertain to serve as a basis for an identification of the predecessor of Merikare.[*]

Scharff and Volten refer for this equation to the order of the Heracleopolitan kings in Burchardt and Pieper (Handbuch der ägypt. Königsnamen, p. 21), where wꜢh-kꜢ-rꜤ Khety (II) and Merikare (kꜢ-mery-rꜤ) appear successively as no. 105 and 106. This, however, was based only on a very questionable addition of the name remainder  preserved in the fourth line of fragment 48 of the Turin royal papyrus (see below). This has the very unlikely prerequisite that the Ramesside scribe of our copy of the royal list which would have used the rare spelling of the name, otherwise only documented in the Herakleopolitan period, in which not only the name of God, but also the other nominal element is prefixed.[*] The equivalence of the kings ẖty and ...y of fragment 48 of the Turin papyrus with Merikare and his father was also adopted by Farina in his new edition. Since he placed the related fragments 48 and 36 in rows 5-9 of column V of the royal list (verso of the papyrus), these two kings now became the penultimate and penultimate rulers of the dynasty, from the end of which it separated only a reign[*] lasting only months. Thus the death of Merikare would have immediately preceded the fall of Herakleopolis.[*]

preserved in the fourth line of fragment 48 of the Turin royal papyrus (see below). This has the very unlikely prerequisite that the Ramesside scribe of our copy of the royal list which would have used the rare spelling of the name, otherwise only documented in the Herakleopolitan period, in which not only the name of God, but also the other nominal element is prefixed.[*] The equivalence of the kings ẖty and ...y of fragment 48 of the Turin papyrus with Merikare and his father was also adopted by Farina in his new edition. Since he placed the related fragments 48 and 36 in rows 5-9 of column V of the royal list (verso of the papyrus), these two kings now became the penultimate and penultimate rulers of the dynasty, from the end of which it separated only a reign[*] lasting only months. Thus the death of Merikare would have immediately preceded the fall of Herakleopolis.[*]

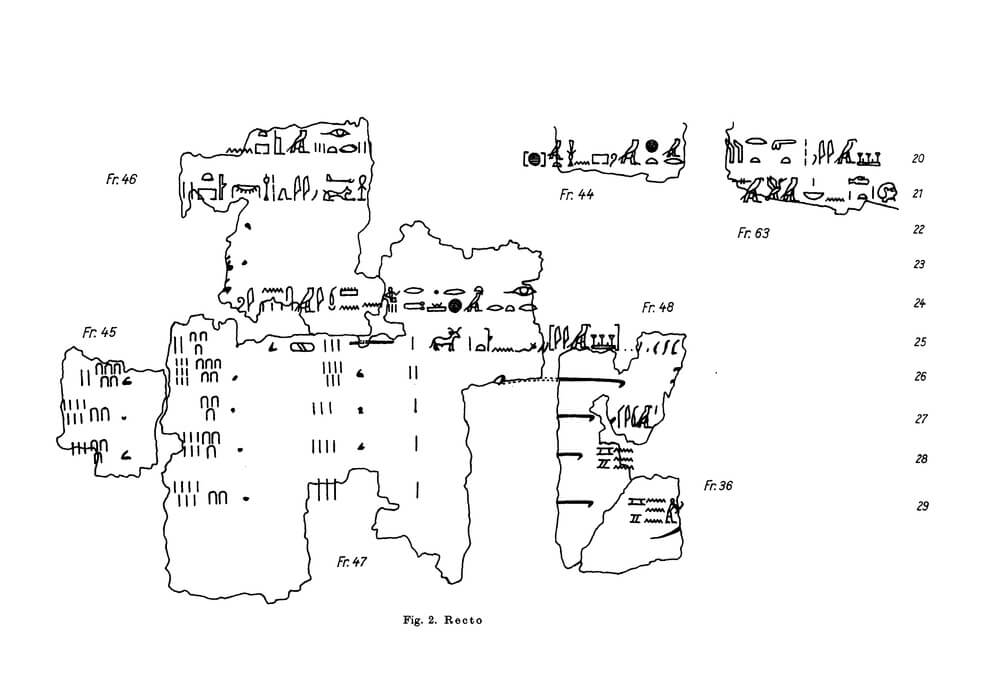

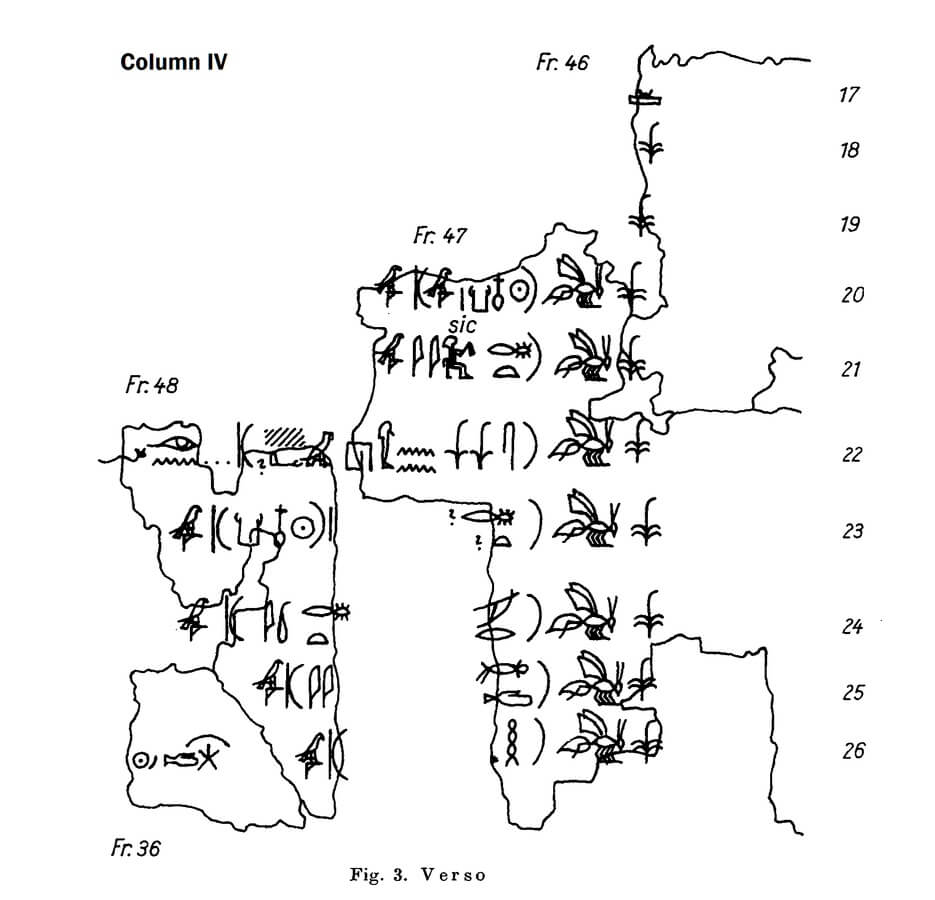

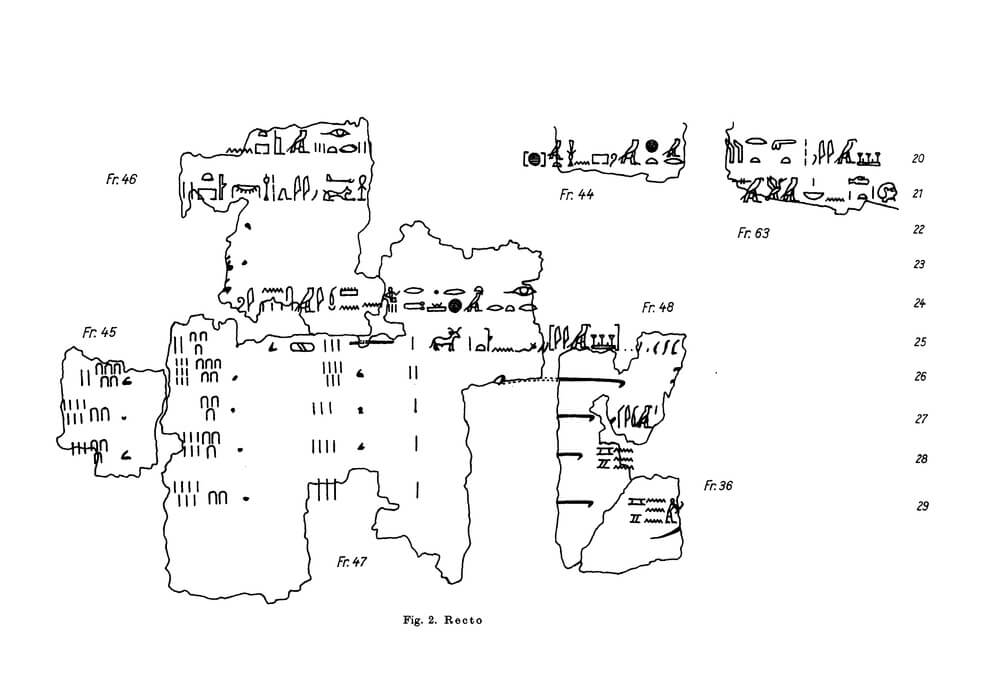

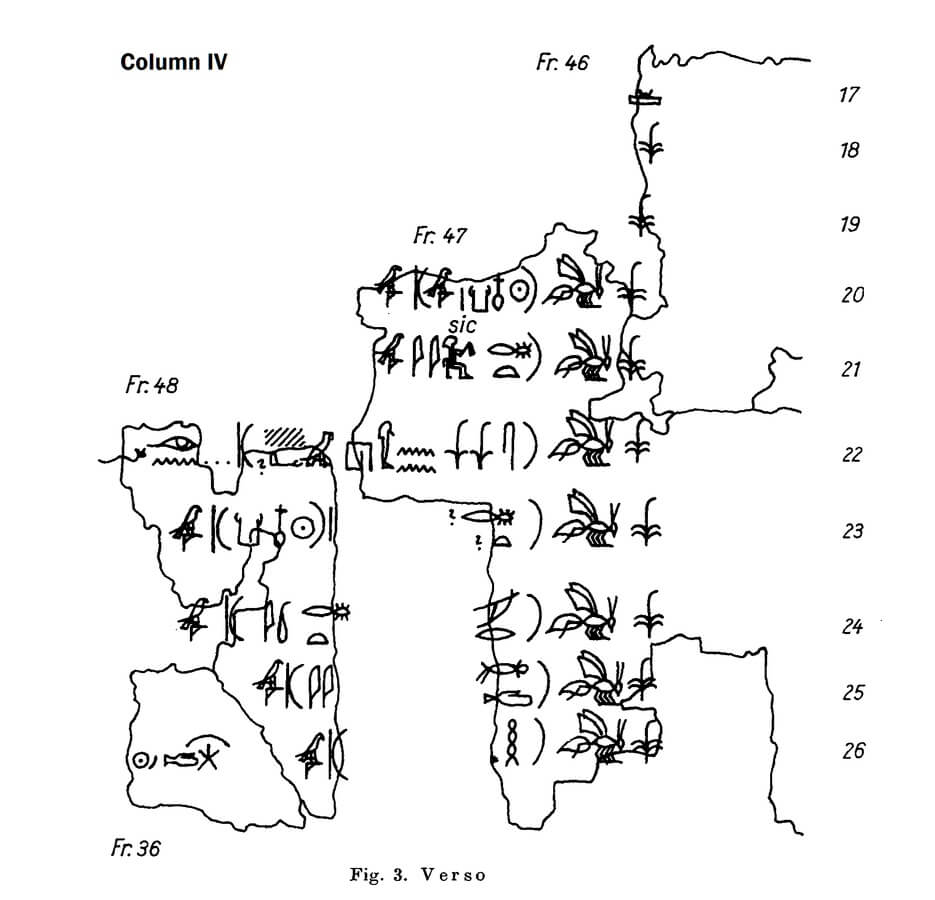

However, this order has since proved erroneous. Sir Alan Gardiner recognized in 1952[*] that fragment 48 + 36 at this place are “out of place”, as the recto of the Papyrus (the tax list) shows. Therefore he has placed them in his “Royal Canon of Turin” (1959) Unplaced fragments. This is of course not a satisfactory solution in view of the historical importance of these fragments. As the occurrence of the name Khety shows, they most probably contain a piece from the 9th/10th dynasty on the verso (royal list) and must therefore belong to either IV 18-26 or V 1-9 of the royal list. However, an examination of the fragments under consideration here, both on the recto and on the verso, now leads to the clear conclusion that there is only one possibility for the classification of fragment 48 + 36: in IV 22-26 of the royal list (see here Fig. 2-3). Already Seyffarth had placed fragment 48 there.[*] However, as Wilkinson stated,[*] the fibers of fragment 48 does not fit exactly to those of fragment 47. Also the sign h (in line 22), the beginning of which is still preserved on fragment 47, is not continued in fragment 48. The latter is therefore to be moved a little more to the left (seen from the verso).

However, two passages seem to contradict this arrangement. In IV 24 of the list of kings the remains of the cartouche on fragment 47 and 48 together result in the strange reading  . It can easily be explained if we assume that the scribe here - as so often in Colossians VI ff. - indicated throne and birth name in a cartouche and inadvertently omitted the ΟOO to be expected at the beginning.[*] Line 23 offers a greater difficulty. Here we have the beginning of a birth name on fragment 47, most likely again Khety.[*] But on fragment 48 in the same line there is now a complete cartouche with the throne name nfr-kꜢ-RꜤ; in front of it there is a vertical line. The only possible explanation seems to be that we are dealing here with a genealogical reference by which this king for some reason should be called son of the nfr-kꜢ-rꜤ listed three lines before. One could therefore supplement IV 23 as follows:

. It can easily be explained if we assume that the scribe here - as so often in Colossians VI ff. - indicated throne and birth name in a cartouche and inadvertently omitted the ΟOO to be expected at the beginning.[*] Line 23 offers a greater difficulty. Here we have the beginning of a birth name on fragment 47, most likely again Khety.[*] But on fragment 48 in the same line there is now a complete cartouche with the throne name nfr-kꜢ-RꜤ; in front of it there is a vertical line. The only possible explanation seems to be that we are dealing here with a genealogical reference by which this king for some reason should be called son of the nfr-kꜢ-rꜤ listed three lines before. One could therefore supplement IV 23 as follows:

The improved list of the dynasty of Herakleopolis, after the rearrangement of fragments 48 + 36, would look like this:[*]

| IV | 18 | nsw-[bit ẖty (?) iry.n.f m nsyt . . . | . . .] |

| 19 | nsw-[bit. . . | . . .] |

| 20 | nsw-bit nfr-kꜢ-rꜤ | [. . .] |

| 21 | nsw-bit ẖty | [. . .] |

| 22 | nsw-bit snn-hꜢ . . .(?) iry.n.f | [m nsyt ...] |

| 23 | nsw-bit ẖt[y zꜢ (?)] nfr-kꜢ-rꜤ | [. . .] |

| 24 | nsw-bit mr[y-. . .]-{r ) ẖty | [. . .] |

| 25 | nsw-bit šd[. . .]y | [. . .] |

| 26 | nsw-bit ẖ[. . .] | Ꜣbdw [. . .] |

| V | 1 | nsw-bit [. . . | . . .] |

| 2 | nsw-bit s(?)[. . . | . . .] |

| 3 | nsw-bit [. . . | . . .] |

| 4 | nsw-bit wsr (?)[. . . | . . .] |

| 5 | nsw-bit [. . . | . . .] |

| 6 | nsw-bit [. . . | . . .] |

| 7 | nsw-bit [. . . | . . .] |

| 8 | [nsw-bit . . . | . . .] |

| 9 | nsw-bit [. . . | . . .] |

| 10 | dmḏ nwswt 18 [. . . . . . . ] |

Unfortunately, it is not possible to make any demonstrable suggestions for identifying one or the other name of this list with one of the rulers known to us from other sources. The founder of the dynasty might have been an Khety (Manetho's Achthoes), but we don't know his throne name. The name of Merikare, who probably belonged to the later kings of the dynasty,[*] may have stood somewhere in V 5-9. How many insignificant successors he may have had, we do not know.

Neither do we know the name of his father, as long as a new fragment of the “teachings” does not give us this.[*] Only with all reservation I dare to make here at the end a suggestion for his identification. Undoubtedly the king must have been one of the most important rulers of the dynasty; after “Merikare” E. 58 he seems to have had a relatively long government. I cannot believe in the usual equation with wꜢh-kꜢ-rꜤ Khety, known only from a later coffin text. Certainly from the words put into his mouth (Merikare E. 70-74) that misfortune had befallen him because of the plundering of the necropolis of Abydos by his soldiers, it cannot be concluded that his own tomb had been plundered. This could then hardly be written in the “teachings” written under his son, in whose reign and under whose responsibility this desecration of the grave must have happened. Rather, these words might refer to the moral responsibility of the king himself in the afterlife; for this new conception this teaching is the most famous example. On the other hand, however, it can be seen with some certainty from the text[*] that the Father of Mericare was the one who regained and colonized the Eastern Delta. Perhaps, therefore, we may equate him with Khety, who was later revered by Chatana, and beyond that - this is of course quite hypothetical - with King nb-kꜢw-rꜤ Khety, whose name was perhaps not accidentally found near the eastern border of Egypt as well. The fact that the story of the “eloquent peasant” was transferred to the reign of this king shows, in any case, that he was remembered as a wise pharaoh of some importance.

*After Africanus. Eusebius also offers here only an even more corrupt version without independent value. Cf. Ed. Meyer, Egypt. Chronology, p. 87.*All dynasties of the papyrus were originally completed by summations. The formula "jrj.n.f m nsyt [x years]" obtained after the name of one of the Herakleopolitan kings (previously erroneously set in V 5; see below for this) does not denote the beginning of a new dynasty: see Helck, Manetho and die egypt. Königslisten (UGAÄ XVIII), p. 84.*The concept of dynasty on which the Egyptian list of kings is based (in the Turin papyrus and also in Manetho's model) does not correspond, as is well known, with our occidental "ruling family" in the genealogical sense. It rather comprises groups of kings of the same residence, of the same origin or of the same sphere of power, for which one can compare the Manethonic dynasty headings, the title to dynasty 12 still preserved in the Royal Papyrus (V 19), but also the Sumerian and Babylonian lists of rulers.*Egypt.

Ḥnn-nsjwt, later

Ḥ(wt-n)-nsw (cf. H. G. Fischer, JAOS 81, 1961, p. 423-425), Assyrian Ḫi-ni-in-ši, Coptic ϩⲛⲏⲥ, Arabian Ahnas or Ahnasija el-Medina. On the historical significance of the city see Kees, Das alte Ägypten (1955), p. 119-129. Neither the excavations at the site of the old city (Porter and Moss, Topogr. Bibl. IV, p. 118-121) nor in the associated necropolis of Sidmant el-Gebel (ibid., p. 115-118) have substantially promoted our knowledge of the Herakleopolitan period.*Here after the main text, Pap. Eremitage 1116 A verso (= Ε. + linenumber).*Ε. 104-105 it says, after praising words for the old residence Memphis (E. 101-104):

iry.n.sn dnjt r Ḥnn-njswt, what Gardiner and Volten translate as "they (the Memphites) have built a dam against Herakleopolis", Erman and Scharff as "they have a dam up to H", while K. Baer, whom I have to thank for some valuable hints, would like to interpret the passage as "they formed a dam for H.". In any case, it is clear that Memphis (then

ḏd-jswt) was not the residence at that time.*They are probably intentionally raised: see Helck, Manetho, p. 51 ff.*Geschichte des Altertums I, Supplement 1925, p. 66-68.*Stock, Die Erste Zwischenzeit Ägyptens (1949): 2175; Hayes, in: Cambridge Ancient History, revised edition (cited: CAH), I (1961): 2160; Parker, in: Encyclopaedia Americana, X (1957): 2155.*v. Beckerath, JNES 21 (1962), p. 140-147. A very similar date (2137) was proposed as early as 1957 by Helck, Manetho, p. 82-83 n. 2.*Now in the Louvre. Not from Asyüt, as indicated by Hayes, CAH I, XX, p. 3; cf. Porter-Moss IV, p. 258 and Gauthier, Livre des Rois I, p. 204, no. 1 (I). The throne name is written here

*rꜤ-jb-mry (see below, n. 37).*In Cairo. A. Kamal, ASAE 10 (1910), p. 185-86.*In New York, Metropolitan Museum. Hayes, Scepter of Egypt I, p. 143, fig. 86. - The one by Gauthier, op. cit. I, p. 204 (II) as well as Drioton and Vandier, L'Egypte (1962), on p. 229 quoted Scarab, which bears the name mr(j)-jb-rꜤ (not mry-jb-rꜤ), does not belong here; it should be attributed to the Hyksos period.*Stele of ḏꜢrj (Cairo 12/22 + 4/9; Petrie, Qurneh, p. 3 and 16-17, pl. II-III; Clere and Vandier, Bibl. Aeg. X, § 18) and stele Cairo 3/25 + 6/11 (Daressy, ASAE 8, 1907, p. 244-45; Clere-Vandier, op. cit., § 30).*ibid. (E. 109) also mentions the teachings of an older king Khety, who is perhaps the founder of the dynasty. Cf. Posener, RdE 6 (1949), p. 33 with n. 4. On the alleged occurrence of mry-jb-rꜤ in the cataract area of Aswan cf. JNES 21 (1962), p. 145-46 with n. 33.*Petrie, Hyksos and Israelite Cities, p. 32, t. XXII Α.*Griffith, PSBA 14 (1892), p. 469.*This is also confirmed by the naming of the king with his throne name. So far no other document has provided us with the birth name of Merikare.*Grave IV, ZI. 3, 9 and 22 Griffith, The Inscriptions of Siut and Deir Rifeh, pl. 13 and 20; Brunner, Die Texte aus den Gräbern der Herakleopolitenzeit von Siut, p. 58 n. 61. The name is written here *rꜤ-kꜢ-mry (see below, n. 37).*In the Louvre. Petrie, History I (1923), p. 133, fig. 86. Cf. Porter-Moss IV, p. 258; Gauthier, Livre des Rois I, p. 209, no. 1 (II).*Quibell, Excavations at Saqqarah 1905-06, p. 21-23, pl. XIII-XV imd 1906-07, pl. VI 2; Firth and Gunn, Teti Pyr. Cemeteries II, t. 27 B; Berlin coffin no. 7796 = Egypt. Inscript I, p. 131-133.*Sh. Adam, ASAE 56 (1959), p. 216, pl. IX Cf Fischer, RdE 13 (1961), p. 107-08.*Adam, loc. cit., p. 208ff., pl. II-III. Perhaps other pharaohs of the early MR were also worshipped here: cf. the double statue Petrie, Nebesheh, pl. XLII, with invocation of SꜤnḫ-kꜢ-rꜤ Mentehotpe (Eleventh Dynasty) as local deity (?).*The name is, as well as in the Royal Papyrus IV 23 and 24, written with double  . Otherwise, besides the usual spelling

. Otherwise, besides the usual spelling  there is also

there is also  (Royal pap. IV 21, the t shows the elongated form similar to a τ, which it gladly adopts in hieratic next to horizontal signs; the following sign there must be a prescription for tj). However, all these variants should reflect the name Khety (ẖty, ẖtj), which was common in the Herakleopolitan period. Cf. Brunner, Lehre des Cheti, p. 25 (to Sallier II 3,9) and 76.*Egypt. probably rꜢ-wꜢtj. For the history of this place see L. Habachi, ASAE 52 (1954), p. 448-479 and Kees, MDIK 18 (1962), p. 1-3.*R. Anthes, The rock inscriptions of Hatnub (UGAÄ IX, 1928), p. 103, pl. 6. In Blackden and Fraser's Collection of Hieratic Graffiti from the Alabaster Quarry of Hat-Nub (1892), pl. XV has one missing cartouche.*Anthes, op. cit., p. 103, pl. 7; Blackden-Fraser, pl. XV 9; Petrie, Tell el-Amarna, pl. XLII.*mry-ḥtḥr (?). The figure at the top of the cartouche is very questionable. The spelling of the name of Hathor as a seated woman would be unusual for this time: see thigh, Frühmitteläg. Stud., § 12.*The prince ḏḥwtj-nḫtw (zꜢ ḏḥwtj-nḫtw) could be the son of ḏḥwtj-nḫtw (zꜢ ḫww) of inscription X. The position which is given to "mry-ḥtḥr" within the 9th/10th Dyrasty (e.g. Burchardt-Pieper, Handbuch, p. 21; Hayes, CAH I, XX, p. 5) is quite arbitrary. Why should he of all people have started a new series of rulers?*Cairo coffin CG 28088 (Lacau, Sarcophages ant. au Nouvel Empire I, pl. XXVII and II, p. 10-19). Cf. Daressy, ASAE 1 (1900), p. 20-21.*Lacau, RT 24 (1902), p. 90; Scharff, Der historische Abschnitt der Lehre für König Merikare (SBAW 1936), p. 9-10 n. 3; Volten, Zwei altägyptische politische Schriften (1945), p. 82-85; Stock, Erste Zwischenzeit, p. 52.*Schenkel, Frühmittelägyptische Studien, p. 120 dates him to the Twelfth Dynasty.*Bibl. or. 8 (1951), p. 170.*So already Ed. Meyer, Gesch. d. Altert. I (1909), § 273 A.*especially Scharff, Volten and Stock in the works cited above; furthermore see Drioton-Vandier, L'Egypte, p. 217 and 629 and Hayes, CAH I, XX. Only Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, p. 112 is more careful.*The approaches proposed by Anthes, op. cit , p. 97-108 and 114 are described by himself as "very uncertain" - a remark which was apparently overlooked in the later treatments of the problem. Cf. Schenkel, op. cit., § 31-35.*For the name mry-kꜢ-rꜤ documented only in the texts from Grave IV in Asyut (see above, n. 19); furthermore once (above n. 11) for mry-jb-rꜤ and once (in the grave of Ꜥnḫ.tj.fj of Mu'alla; Vandier, Mo'alla, Inscr. 16, 18 lind p. 157-159) for a nfr-kꜢ-rꜤ. Cf. Schenkel, op. cit., p. 150.*King's name lost. Of course can not be used here with Burchardt-Pieper, manual, p. 21 the name of nb-kꜢw-rꜤ Khety shall be used.*For example, in the chronological overviews at Drioton-Vandier, L'Egypte, Stock, Erste Zwischenzeit and Hayes, CAH.*The Turin Canon of Kings, privately circulated photostat edition.*Cf. Lepsius, selection of the most important documents, pl. IV.*The Fragments of the Hieratic Papyrus at Turin (1851), pl. II.*The name mr[y-jb]-<rꜤ> could be used here, for example ḥty can be supplemented.*The remains of signs described by Gardiner, Royal Canon, p. 17 as “scanty and illegible” should clearly be an

(Royal pap. IV 21, the t shows the elongated form similar to a τ, which it gladly adopts in hieratic next to horizontal signs; the following sign there must be a prescription for tj). However, all these variants should reflect the name Khety (ẖty, ẖtj), which was common in the Herakleopolitan period. Cf. Brunner, Lehre des Cheti, p. 25 (to Sallier II 3,9) and 76.*Egypt. probably rꜢ-wꜢtj. For the history of this place see L. Habachi, ASAE 52 (1954), p. 448-479 and Kees, MDIK 18 (1962), p. 1-3.*R. Anthes, The rock inscriptions of Hatnub (UGAÄ IX, 1928), p. 103, pl. 6. In Blackden and Fraser's Collection of Hieratic Graffiti from the Alabaster Quarry of Hat-Nub (1892), pl. XV has one missing cartouche.*Anthes, op. cit., p. 103, pl. 7; Blackden-Fraser, pl. XV 9; Petrie, Tell el-Amarna, pl. XLII.*mry-ḥtḥr (?). The figure at the top of the cartouche is very questionable. The spelling of the name of Hathor as a seated woman would be unusual for this time: see thigh, Frühmitteläg. Stud., § 12.*The prince ḏḥwtj-nḫtw (zꜢ ḏḥwtj-nḫtw) could be the son of ḏḥwtj-nḫtw (zꜢ ḫww) of inscription X. The position which is given to "mry-ḥtḥr" within the 9th/10th Dyrasty (e.g. Burchardt-Pieper, Handbuch, p. 21; Hayes, CAH I, XX, p. 5) is quite arbitrary. Why should he of all people have started a new series of rulers?*Cairo coffin CG 28088 (Lacau, Sarcophages ant. au Nouvel Empire I, pl. XXVII and II, p. 10-19). Cf. Daressy, ASAE 1 (1900), p. 20-21.*Lacau, RT 24 (1902), p. 90; Scharff, Der historische Abschnitt der Lehre für König Merikare (SBAW 1936), p. 9-10 n. 3; Volten, Zwei altägyptische politische Schriften (1945), p. 82-85; Stock, Erste Zwischenzeit, p. 52.*Schenkel, Frühmittelägyptische Studien, p. 120 dates him to the Twelfth Dynasty.*Bibl. or. 8 (1951), p. 170.*So already Ed. Meyer, Gesch. d. Altert. I (1909), § 273 A.*especially Scharff, Volten and Stock in the works cited above; furthermore see Drioton-Vandier, L'Egypte, p. 217 and 629 and Hayes, CAH I, XX. Only Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, p. 112 is more careful.*The approaches proposed by Anthes, op. cit , p. 97-108 and 114 are described by himself as "very uncertain" - a remark which was apparently overlooked in the later treatments of the problem. Cf. Schenkel, op. cit., § 31-35.*For the name mry-kꜢ-rꜤ documented only in the texts from Grave IV in Asyut (see above, n. 19); furthermore once (above n. 11) for mry-jb-rꜤ and once (in the grave of Ꜥnḫ.tj.fj of Mu'alla; Vandier, Mo'alla, Inscr. 16, 18 lind p. 157-159) for a nfr-kꜢ-rꜤ. Cf. Schenkel, op. cit., p. 150.*King's name lost. Of course can not be used here with Burchardt-Pieper, manual, p. 21 the name of nb-kꜢw-rꜤ Khety shall be used.*For example, in the chronological overviews at Drioton-Vandier, L'Egypte, Stock, Erste Zwischenzeit and Hayes, CAH.*The Turin Canon of Kings, privately circulated photostat edition.*Cf. Lepsius, selection of the most important documents, pl. IV.*The Fragments of the Hieratic Papyrus at Turin (1851), pl. II.*The name mr[y-jb]-<rꜤ> could be used here, for example ḥty can be supplemented.*The remains of signs described by Gardiner, Royal Canon, p. 17 as “scanty and illegible” should clearly be an  and above that the beginning of an

and above that the beginning of an  .*Compare e.g. the overview given by Schenkel, op. cit., p. 140.*This conclusion, drawn mainly from his synchronism with ḥty II by Asyut, is also accepted by Schenkel, op. cit., p. 140.*I owe it to G. Posener to inform me that traces of two vertical signs (reeds?) are still recognizable at the end of the original in the lost cartouche of the Father of Merikare (Ε. 1), thus nothing would stand in the way of an addition to the name ḥty.*Especially E. 88-90: “See, a landing peg is struck in the area which I have newly established (lit.: made) in the east, up to ḥbnw (and) up to the Horusway, populated with citizens, filled with people of the best of the whole country, in order to ward off their (i.e. the Asians') attack”.

.*Compare e.g. the overview given by Schenkel, op. cit., p. 140.*This conclusion, drawn mainly from his synchronism with ḥty II by Asyut, is also accepted by Schenkel, op. cit., p. 140.*I owe it to G. Posener to inform me that traces of two vertical signs (reeds?) are still recognizable at the end of the original in the lost cartouche of the Father of Merikare (Ε. 1), thus nothing would stand in the way of an addition to the name ḥty.*Especially E. 88-90: “See, a landing peg is struck in the area which I have newly established (lit.: made) in the east, up to ḥbnw (and) up to the Horusway, populated with citizens, filled with people of the best of the whole country, in order to ward off their (i.e. the Asians') attack”.

preserved in the fourth line of fragment 48 of the Turin royal papyrus (see below). This has the very unlikely prerequisite that the Ramesside scribe of our copy of the royal list which would have used the rare spelling of the name, otherwise only documented in the Herakleopolitan period, in which not only the name of God, but also the other nominal element is prefixed.[*] The equivalence of the kings

. It can easily be explained if we assume that the scribe here - as so often in Colossians VI ff. - indicated throne and birth name in a cartouche and inadvertently omitted the ΟOO to be expected at the beginning.[*] Line 23 offers a greater difficulty. Here we have the beginning of a birth name on fragment 47, most likely again Khety.[*] But on fragment 48 in the same line there is now a complete cartouche with the throne name