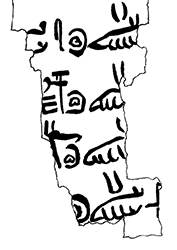

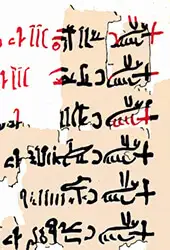

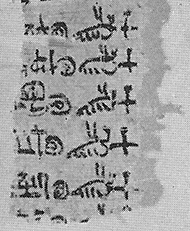

The Turin king list is an ancient papyrus roll that contains the longest sequence of kings from ancient Egypt that exists and is written in hieratic. Hieroglyphs require meticulous attention to detail and take a long time to write. In contrast, the closely related hieratic is a cursive script that uses simplified and connected characters. Throughout most of ancient Egyptian history, hieratic was used for everyday writing.

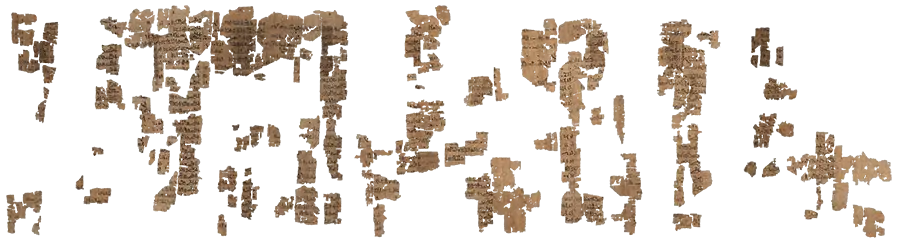

A hieratic papyrus at the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy, is without a doubt the most important king list of Ancient Egypt. It is often referred to as the Turin king list, or the Royal Canon of Turin, originating from Champollion’s 1824 description as “un véritable tableau chronologique, un canon royal”, a true chronological timeline, a royal canon.1 The papyrus is in very poor shape, less than a third of it remains, having crumbled into hundreds of tiny fragments by handling and during the transport to Italy, after its discovery around 1820. The king list is written on the back side of a Nineteenth Dynasty discarded administrative papyrus from the reign of Ramesses II.

The intact papyrus would have contained the names of 223 kings. Of these, 126 are complete or partial, and the remaining 97 entirely lost in the lacuna. Many of the preserved names does not appear inscribed on the Abydos, Saqqara, or Karnak Canons from the New Kingdom. Despite its importance, we had to rely on traced facsimiles from the 1840’s and 1850’s, which naturally contain a few minor errors. Only Farina’s low quality photos were available until the Egyptian Museum in Turin released high quality photos in September of 2019. The papyrus has deteriorated, mainly due to to mounting and re-mounting, since the reconstruction in 1826. However, the facsimiles offer us a glimpse of a better preserved king list, as several signs seen in the facsimiles, has been irretrievably lost.

Several notations of lacuna are present, originating from a prototype or vorlage of the papyrus, and used where a part of the source text was missing or unreadable. The chronological sequence of the kings seems to be quite reliable, as it even include kings or queens left out of the other king lists.

History

The papyrus was lost for some 3000 years, perhaps buried in a forgotten tomb or temple near Thebes in Upper Egypt. Unlike the other king lists of the New Kingdom, it was not produced for religious purposes, but instead as an administrative chronological reference aid, containing the names and reign lengths of the kings of the Two Lands. There is no evidence of any intentional exclusion or supression of kings, as contemporary and ephemeral kings are included, even the foreign kings of the Second Intermediate Period.

The Turin king list is an ancient Egyptian full-size papyrus roll

written in hieratic, sadly it is in very poor shape, only one third

of the full papyrus remains. Its original use was as a tax-register

dating to the reign of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE), evident from the text, "Inspector of the wells of

Rolls of papyrus were manufactured with the horizontal fibres on the inside, and the vertical fibres on the outside. The natural way to write on papyri, was on the inside of the roll (i.e. along the horizontal fibres), which also served to protect the writing when it was rolled up.3 This side is called the recto, or front side.

It was first assumed that the king list was the initial document, however, as the tax-register was written along the horizontal fibres, it naturally must be the original.4 So, the tax-register is written on the recto, or front side, with the king list on the verso, or back side. There is no indication as to when the king list was written, whether a few months, years, or even decades later.

Discovery

The papyrus was likely intact when rediscovered in the late 1810s near Thebes in Egypt; however, the provenance is unknown. Being suddenly exposed to the elements and being handled by human hands after thousands of years in isolation, caused the fragile papyrus to begin to crumble. Bernardino Drovetti, the French Consul-General of Egypt at the time, acquired the papyrus sometime in the 1815–22 timeframe. Although it is unknown if he acquired it himself, it is more likely that one of his agents did. The note by Maspero as to its discovery was likely based on some accurate information.

[the Papyrus] was purchased in Thebes almost untouched by Drovetti around 1818, and unintentionally mutilated during his transport of it. The leftovers were acquired by the collection of the Piedmontese government in 1820 and deposited in the Museum of Turin, where Champollion saw them in 1824.Gaston Maspero.5

However, the story invented by Winlock was fabricated to add colour to the likely unremarkable discovery.

When the papyrus was found by Drovetti, either in 1823 or in 1824, it was apparently complete, and he put it into a jar which he tied about his waist, mounted his donkey, and proceeded to ride into town. The joggling which the jar got along the path was disastrous.Herbert Winlock.6

Drovetti clearly failed to note the importance of the papyrus, and simply stored it in a box together with many other papyri he acquired in Egypt.7 As there is no clear provenance of the discovery, the archaeological context is irretrievably lost. Drovetti and his agents amassed a huge collection of Egyptian artefacts, and textual papyri did not receive special care8 but were unceremoniously dumped together in a big box by the hundreds. It was, after all, only a papyrus without elaborate drawings of gods and kings. As the European market in Egyptian artefacts was rapidly growing, it was to be sold to the highest bidder.

Drovetti had the antiquities he acquired in Egypt shipped and stored in Livorno already in 1820,9 and after France declined to buy his collection, he started negotiations with his native Piedmont. Victor Emmanuel I, the King of Sardinia, showed great interest in the collection, but Drovetti’s asking price of 400,000 lire was an enormous sum for the small kingdom. The negotiations stalled when the king abdicated in favour of his brother Charles Felix. Ultimately, Drovetti accepted the deal, and the king signed the purchase on January 24, 1824.10

The collection included 170 Egyptian papyri,11 and was only the first of three collections that he sold.12 Transported from storage in Livorno to Genua by sea, from there to Turin by wagons, it arrived in February of 1824. Housed in the Academy of Sciences building, the collection was unpacked immediately and temporarily placed in rooms on the ground floor. The Drovetti collection de facto became the Egyptian Museum of Turin, a detached section of the Museum of Antiquities. Formally inaugurated on June 10, 1824, the Museum was still undergoing planning and construction, but not opened to the public until 1832.

Champollion

Towards the end of 1823, the French scholar Jean-François Champollion completed his Summary of the hieroglyphic system of the ancient Egyptians,13 laying the foundation for the decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. His decipherment effort was being hampered by inaccurate and unreliable transcriptions of the available hieroglyphic texts, which contained errors and omissions. To further the research, it was imperative to obtain new error-free transcriptions of the texts held in the Egyptian collections throughout Europe, most of them in Italy. His plan was to visit the collections and make exact copies himself.

To that end, he arrived in Turin on the morning of June 7, 1824. Two days later he received the necessary documents from the Minister of the Interior, Count de Cholex, to begin his research, and, guided by his friend Count Balbo, President of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin, he entered the vast halls of the palace holding the newly acquired Drovetti Collection.

Over the next months, Champollion established his work programme and succeeded in mastering the new results that were coming his way. Amadeo Peyron, Hellenist and faculty professor, and Costanzo Gazzera, Orientalist and librarian of the university quickly became Champollion’s best friends and helpers. Together they started spreading the results obtained, both orally and in writing, to the curious public. Champollion intended to make copies of the entire collection, and tirelessly they helped him unpack and arrange the smaller items, as well as copying, making impressions and casting them in wax or plaster.

In addition to the enormous task of working through the entire collection, he also carried out the painstaking examination of the papyri in the Museum, which Count Cholex had entrusted to him, giving him unlimited authority, apparently over the head of San-Quintino, who was appointed curator of all the Egyptian antiquities in Turin at the time and who had already taken most of the Drovetti Collection papyri over to the university building. San-Quintino was appalled that Champollion was granted access to the documents, and ultimately confronted him as if he were a presumptuous intruder, which gave rise to very embarrassing scenes; incidentally, the director’s bad moods were well known.

Champollion had already made a serious complaint about the director on June 18. A second letter of complaint was sent to the minister on August 24, as it was now a question of opening, organizing and identifying 175 papyri, of which only 20 had been unrolled. In the end, he was given the keys to the museum, and of course this gave rise to new feuds as time went on.

In early November, after weeks of restless work, he also learned about a box of papyri scraps stashed away at the Palace.14 However, he insisted on seeing them all, down to the last shred, so it was agreed that they were to be laid out on a table for him to peruse the next morning.

On November 6th, he wrote:

Upon entering this room, I saw a table ten feet long and covered with a thick layer of papyri shreds across its entire width, at least half a foot thick... I immediately decided to examine all remains that covered this table of desolation, one by one. With restrained breath, for fear of turning them to dust, I collected this or that piece of papyrus, which may be the last and only remains of the memory of a king who may have lived in the immense palace of Karnak.

I am convinced that these papyri belonged to the archives of a temple or other public depository. However, the most important of these, one whose mutilation I will ceaselessly deplore, is a historical treasure, a chronological list, a true royal canon in hieratic writing, containing four times as many dynasties as an intact Abydos Table. Most remarkable is that none of the names are in any way similar to those of the Abydos Table. It seems equally certain to me that the remains of this historical Canon dates to no later than the Nineteenth Dynasty.Champollion's letter to his brother.15

He spent nine more days fervently searching for the remnants of this priceless papyrus amidst thousands of scraps, until he finally had gathered 40 pieces, which he was able to bring to 46, and a little later to 50 with much effort and patience. “Finally,” he writes on November 15, “I have gathered from the remains of this royal canon, which is Manetho in hieratic writing, some 160–180 royal throne names; many are intact, but many are – be it at the beginning or at the end – mutilated. A number follow the name, which will be a means of chronological arrangement. The most striking result is undoubtedly evidence that the Egyptians, at a very remote time, counted nearly 200 reigns before the Seventeenth Dynasty - since this text is found among archival remains that do not exceed past the Twentieth Dynasty; for in all these fragments there is not a single cartouche similar to those of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth or subsequent dynasties.”

Since the fragments could not even come close to forming a whole text, he concluded that only a small part of the papyrus was saved from destruction and said: “It is the greatest disappointment of my literary life to have discovered this manuscript in such a deplorable state. I will never console myself; the wound will bleed for a long time.”

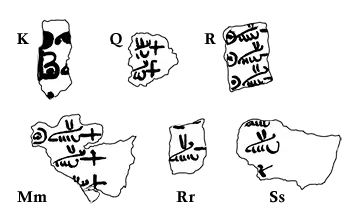

Champollion made tracings of each fragment in a booklet,16 providing each with a unique Latin letter, ranging from A to Z, and when the alphabet ran out, continued from Aa to Vv. Only fragment Uu show the recto, and it is in fact the same fragment as the already traced Nn, which does show the verso.

Though the king list was an important discovery, he returned to work, copying as much of the collection as possible, all while expanding his knowledge about the ancient Egyptian language. It should be noted that Champollion made no effort to reconstruct the papyrus, he just simply copied the fragments he discovered. Neither did he publish the fragments or names he found, a task that was left to his brother Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac, some twenty years after Jean-François untimely death in 1832.17

For years rumours persisted that the jealous San-Quintino had secretly removed fragments. The rumours started after Seyffarth’s reconstruction in 1826, who had spent weeks patiently sorting through the debris from the “Table of desolation,” examining the scraps one by one, and he not only managed to reunite a number of fragments so well that they appeared to not have been broken in the first place, but also found more than 100 additional fragments that Champollion missed. This did not sit well with Champollion, or his inner circle, and accusations started flying, no doubt fuelled by the well-known enmity between Seyffarth and Champollion. In retrospect, the claim that San-Quintino hid fragments from the Frenchman is certainly possible but not corroborated by fact, and could simply be an attempt to mitigate Seyffarth’s clearly superior arrangement of the papyrus.

The tracings of Champollion are not entirely accurate, but I have managed to locate fragments Dd and Ii that escaped notice by Gardiner.

fr. Ii joins fragments T and Jj, forming fr. 98, containing the titles for 9.11-13.

This leaves only the K, Q, R, Mm, Rr, and Ss fragments still unidentified.

It should come as no surprise that Champollion only found parts of 21

fragments during his cursory inspection, while Seyffarth diligently

devoted several weeks examining every scrap managed to find a total of

164. Further examination by modern scholars shows that though most of

the fragments added by Seyffarth indeed belong to the papyrus, there is

at least 25 that does not. Unsurprisingly there is also at least 15

blank fragments.

As luck would have it, it was very fortunate for Egyptology that it was Champollion

that discovered the king list. It is arguably possible that we would have

been ignorant of its importance, perhaps even its existence, if lesser able

hands had examined the scraps before the Frenchman, and then discarded the

fragments as garbage.

Reconstruction

Written right to left, as is usual with hieratic papyri, most lines yield the name of a particular king, followed by a number of years, months and days ruled. Unlike the other king lists, it include the Hyksos kings, ephemeral rulers, and those only ruling over small territories.

The poor state of the papyrus only allows for a mostly conjectural reconstruction, but by close examination of the fibres, as well as comparing the writing on both sides of the papyrus, the placement of the fragments can be determined with a good amount of accuracy. Many of the royal names and their chronological positions originate with this unique and invaluable papyrus.

Seyffarth

The Saxon scholar Gustav Seyffarth had developed a flawed hieroglyphic system, where the signs were purely phonetic, which was competing with Champollion’s system. Seyffarth’s system was proven to be incorrect by none other than Champollion himself, a fact which Seyffarth refused acknowledge. It is clear from their correspondence that after meeting in Italy, they soon became enemies, though socially they kept up a civil and courteous façade.

Seyffarth arrived in Turin in late May of 1826,18 and immediately began the restoration of the multitudes of papyri in the Drovetti collection, among them the king list.

Champollion might have discovered the fragments, but Seyffarth did the actual work of puzzling all the pieces together into a somewhat cohesive papyrus. His careful consideration of the fibres, coloring, and the writing on the both sides would prove to be crucial, as his arrangement of the fragments resulted in the king list as we know it today.

The Egyptian Museum of Turin preserved a huge box with at least half a million of papyri fragments, the largest were three inches long and two inches broad. I devoted six weeks to a close examination of each of the fragments, and put them together as far as was possible. The papyrus I thus obtained was eight feet long and one foot high.From Seyffarth’s autobiography.19

It was obvious from the start that the fragments of the papyrus were only small parts of a whole text, and to be understood, in need of being reassembled to find a context. This meant examining and sorting through the countless fragments found in the box, from many different papyri, and try to find which fragments belonged to the papyrus.

Seyffarth patiently sorted through thereconstructionsdata vast pile of fragment debris, examining the scraps one by one, and managed to reunite some fragments so well that they do not appear to have ever been broken, as seen in the facsimiles of Lepsius and Wilkinson. His diligence was rewarded as he found more than 100 fragments neglected or missed by Champollion, who did not go through the debris as thoroughly as he might have.

Champollion claimed that San Quintino hid fragments from him, which was probably only an attempt to mitigate his hurt pride, when confronted with Seyffarth’s superior arrangement.20 It is to Seyffarth’s merit that he did not try to restore the papyrus according to his own beliefs about the hieroglyphic system, instead he took a scientific route by matching the fragments according to fibres, colour, thickness, and writing. Seyffarth’s arrangement is exceptional, as subsequent reconstructions show that he positioned most of the fragments in their correct position. In all he restored some fifteen papyri during his time at the Museum.21

When the arrangement was as complete as Seyffarth could make it, he glued the fragments together with blotting paper. Seyffarth did not publish his restoration, but his unpublished tracings of the papyrus is in the archives of the Brooklyn Museum.22 Champollion saw Seyffarth as a charlatan.23 His opinion of Seyffarth could explain why he did not trust in his arrangement of the papyrus. Add to this that Seyffarth saw Champollion as The Enemy,24 and did his best to discredit the Frenchman’s system to anyone that would listen.

When Champollion saw Seyffarth’s arrangement of the papyrus, instead of acknowledging the accomplishment, he saw only conspiracy and deceit.25 So much that he accused San Quintino, who was cataloguing Drovetti’s collection at the Museum, of having hidden fragments from him, only to later surrender them to Seyffarth. This claim was circulated in Champollion’s circle of friends, and his brother later reiterated the claim.26 Thought it should be noted that the Champollion-San Quintino feud was well known at the time, and the possibility cannot be entirely discarded. San Quintino was making a detailed inventory of the collection for the Academy as it was being unpacked, and it would seem probable, even likely, that after Champollion had examined the pile of papyri debris, his scrutiny resulted in him finding fragments that were neglected or missed by the Frenchman.

Champollion’s death in 1832 did not deter Seyffarth from writing an anecdote about the discovery of the papyrus:

Before me, Champollion had examined the same box of fragments and declared it completely useless, and out of ignorance and arrogance even had half of it thrown into the privy during the absence of the Inspector, depriving the world of one of its most precious treasures.G. Seyffarth 1843.27

Seyffarth repeated this (likely invented) story of ill will towards Champollion in his autobiography.28 It is obvious that Seyffarth’s animosity towards the Frenchman did not end with Champollion’s death. The famous Champollion’s rejection of Seyfarth’s arrangement led people to consider it with scepticism, if not outright scorn. The support for the Frenchman was almost universal, as he was after all the expert on hieroglyphics, while the views of Seyffarth were incorrect. The rejection was exasperated by Champollion’s untimely death, which reinforced the derision of the arrangement without any objective analysis or investigation. Lest they disagree with the late master, the subject of the papyrus was neglected, even avoided, despite its obvious value to scholars. However, this was about to change—albeit slowly.

The polemic surrounding the arrangement of the papyrus lasted several years, but eventually scholars who took the time to examine the papyrus, realised that the arrangement was indeed very good. The first account in more than a decade was by Samuel Birch of the antiquities department of the British Museum, who held a presentation at the Royal Society detailing his analysis of the king list in November 1841.29

Facsimiles

The pioneering German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius visited Turin in December 1835, and made careful traces of both sides of Seyffarth’s arrangement.30 While in Paris three years later, Lepsius obtained copies of Champollion’s isolated fragments, courtesy of his brother. The following year, in London, Lepsius saw Samuel Birch’s copy of Édouard Dulaurier’s copy of Seyffarth.31 Lepsius also saw a manuscript of twelve pages that was stolen from Champollion by his pupil Salvolini who deviously claimed it as his work.32

After noticing discrepancies between the different copies that was circulating among the scholars, he returned to Turin in 1841, to once and for all establish that he indeed had an exact copy. He also wanted to verify that he had correctly identified the location in the papyrus of the Twelfth Dynasty.33

In 1842, Lepsius published "A selection of important ancient Egyptian documents",34 with numbered fragments from 1 to 164. Taking special care to present the papyrus as it was arranged by Seyffarth, without any corrections or amendments, he also chose to omit the admittedly less important tax-register, and included no commentary at all, letting the facsimiles speak for themselves. These facsimiles are still very important today, as the papyrus has since deteriorated further, from handling, mounting and remounting, and of course, time.

The edition of Lepsius made the content of the papyrus available for scholars to study, and though still a touchy subject, studies slowly began to appear. Wilkinson’s edition added to the credibility of Seyffarth’s arrangement, and finally broke the camels back. However, the studies were slow in appearing and concerned themselves more with aligning the king list to fit with Manetho’s list of kings. The director of the Turin Museum at the time, Francesco Barucchi, mentioned the king list only in passing in 1844.35 The following year, Christian Bunsen, a German diplomat and scholar, looked into some of the details preserved in the king list.36 It was not a very long or detailed study, but a good start nonetheless. In 1846, famed Assyrologist Edward Hincks examined the correspondence of the king lists with Manetho, but again, it was not a very thorough investigation.37

The French architect Jean-Baptiste Lesueur tried to make sense of the Manethonian tradition, by trying to reconcile the two in 1846.38 His facsimiles are identical copies of Lepsius, but with most of the smaller fragments left out. He attempted to complete the king list by finishing partial signs, and adding whole lines of text in red ink, which are of course inaccurate. Ironically, his facsimiles does not include the signs that were written in red ink on the papyrus.

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson, the Father of British Egyptology, visited the Turin Museum in 1849 and also made tracings of the hieratic on both sides of the papyrus. His edition was published in 185139 and is nearly identical to Lepsius’, whose edition he happily praised as complete.40 There are only a few minor differences, but most importantly; Wilkinson also included the tax-register on the reverse, which Lepsius had omitted. While Lepsius included no commentary, Wilkinson wrote a detailed description, and included in a new, and more detailed examination of the papyrus by Hincks.41

It should be noted that the facsimiles of Lepsius and Wilkinson are not always accurate, but since they are not photographs, naturally a few minor errors are to be expected.42 They are still very relevant, due to the much deteriorated state of the papyrus today. The addition of Wilkinson’s edition seems to have added incentive for further study of the king list. The first catalogue of the Turin Museum was produced in 1855 by Pietro Camillo Orcurti, who described the content of each column briefly.43 Four years later, Heinrich Brugsch examined the names found in the king list, and included a plate with a transcription of the fragments from the Fourth to Twelfth dynasties.44

Franz Joseph Lauth’s examination45 of Manethonian tradition included the king list in his handwritten book in 1865. The following year, Vicomte de Rougé researched the first six dynasties, utilizing the corresponding parts of the Turin king list.46 Alfred Wiedemann described the papyrus briefly in his Egyptian History in 1886,47 but the first real investigation was performed by the historian Edouard Meyer in his "Egyptian Chronology" in 1904.48

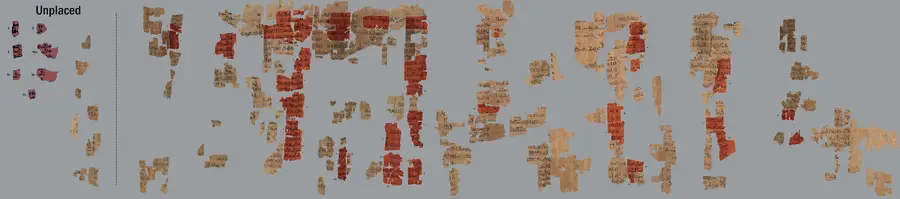

The 1930 restoration

When Giulio Farina took over as director of the Egyptian Museum in Turin in 1928, he had a workshop set up for the restoration of the papyri of the Museum, and managed to bring in the papyrus conservation specialist Dr. Hugo Ibscher from Berlin in 1930.49 Ibscher detached the fragments from the blotting paper on which Seyffarth had glued them, and began the arduous task of re-examining and reassembly of the papyrus. The mounting of the papyrus by Seyffarth remained untouched for more than a century, until Ibscher’s thorough examination resulted in the removal of many fragments from Seyffarth’s arrangement that do not belong to this papyrus.50 The process of removing the papyrus from the blotting paper caused damage along the edges and many minute signs or traces of signs were lost, making the facsimiles of Lepsius and Wilkinson all that more valuable. To protect the papyrus, it was placed between two glass panes in three separate frames. While Ibscher only worked on the restoration for a few weeks, the restoration was long and difficult, and was not completed until October of 1934.51

Farina examined every aspect of the papyrus for years, and rearranged and added a few fragments compared to Ibscher’s mounting.52 His photographs of the papyrus are unfortunately of rather poor quality. This edition contain the first complete hieroglyphic transcription of the hieratic which is still valuable, but as additional research has proven, now mostly obsolete as fragments has been rearranged. All earlier studies concentrated more on the chronological aspect than on the actual content of the king list, and only included parts of Lepsius or Wilkinsons facsimiles. The new mounting introduced new fragments not present in Seyffarth’s arrangement. These fragments were left unnumbered, instead indicated as "Fr. ?" by Gardiner.

The Museum in Turin have four frames with mostly tiny unpublished fragments that could belong to the papyrus.53

Modern studies

The advances in Egyptology since the discovery of the king list are nothing short of astounding. It is however very surprising that modern Egyptology still have not made a complete study, to once and all settle things. Instead several noteable scholars have had to make their own investigations, most which unfortunately have been limited in scope.

Essential to any study of the king list, Gardiner’s The Royal Canon of Turin54 contain detailed information on the fragments and the transcribed hieroglyphic content of the papyrus, but no photographs or facsimiles of the hieratic. Gardiner examined the papyrus several times, and a number of fragments were marked as unplaced as their positions could be established with certainty.55 There are no translations or commentaries, except short notes about the transcript. The position of a few fragments were changed compared to Farina, but most remained in the same place Seyffarth had put them more than a century earlier. The full transcription can be found in Kitchen’s Ramesside Inscriptions II.56

The studies after Gardiner have been scattered, since many Egyptologist saw the research as exhausted. There have been notes and comments by Jürgen von Beckerath57 58 59 60 61 62 63, Detlef Franke64 65, Jaromír Málek66, Winfried Barta67, Wolfgang Helck68, and most recently, Kim Ryholt.69 70 71 72 73

It is clear that further research is needed when you consider the 1997 study by Kim Ryholt. While concentrating on the Second Intermediate Period kings (columns 7-11), careful examination of fibre correspondence between the fragments show that there still is work to be done to find the correct positions of the fragments. Ever since Seyffarth’s restoration there are many fragments whose position remain uncertain or questionable. Ryholt proved that a completely new column of divinities must be inserted between the older columns I and II, from fragments that had been placed incorrectly in the eariler reconstructions.74

The 2022 restoration

In the summer of 2022, the papyrus was painstakingly cleaned of old glue and some of the fragments were rearranged. A new edition is expected to be published in 2024, the 200th anniversary of the discovery.

References

Bibliography

- Adler, William, and Tuffin, Paul., 2002. The Chronography of George Synkellos Oxford: University Press.

- Barta, Winfried., 1983. Bemerkungen zur Rekonstruktion der Vorlage des Turiner Königspapyrus. Göttinger Miszellen, 64: 11–13.

- Barucchi, Francesco., 1844. Discorsi critici sopra la cronologia egizia Turin: Stamperia Reale.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von., 1999. Anmerkung zu zwei unbeachteten Fragmenten des Turiner Königspapyrus. Göttinger Miszellen, 168: 19–21.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von., 1984. Bemerkungen zum Turiner Königspapyrus und zu den Dynastien der ägyptischen Geschichte. SAK 11: 49—58.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von., 1976. Die Chronologie der XII. Dynastie und das Problem der Behandlung gleichzeitiger Regierungen in der ägyptischen Überlieferung, SAK 4: 45-57.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von., 1966. “Die Dynastie der Herakleopoliten (9./10. Dynastie)”, ZÄS 93: 13–20.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von., 1995. “Some Remarks on Helck's ’Anmerkungen zum Turiner Königspapyrus’”, JEA 81: 225–27.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von., 1964. Untersuchungen zur politischen Geschichte der Zweiten Zwischenzeit in ägypten Glückstadt: Augustin.

- Ben-Tor, Daphna, et. al., 1999. Seals and Kings, BASOR 315: 47–74

- Birch, Samuel., 1843. Observations upon the hieratical canon

of Egyptian kings at Turin. TRSL, S.2, Vol. 1: 203-8

- Brugsch, Heinrich., 1859. Histoire d’Égypte des les premiers de son existence jusqu’a not jours. Première partie, l’Égypte sous les indgigénes. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

- Bunsen, Christian C. J., 1845. Aegyptens Stelle in der Weltgeschichte. Vol. 1. Hamburg: Perthes.

- Černý, Jaroslav., 1952. Paper and books in Ancient Egypt. London: Lewis.

- Champollion, Jean-François., 1824. Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens Paris: Imprimerie Royale.

- Champollion, Jean-François., Canon hiératique des dynasties

égyptiennes. Papiers de J.Fr. Champollion, vol. 16. BNF NAF

20318

- Champollion, Jean-François., 1824. Papyrus Égyptiens. Bulletin des sciences historiques, antiquités, philologie 2: 297–303.

- Champollion-Figeac, J. J., 1851. De la table manuelle des

Rois et des dynasties d’Égypte ou papyrus royal de Turin. Revue Archéologique 7.2: 397–402, 461–472, 589–599, 653–665.

- Dawson and Uphill., 1972. Who was who in Egyptology. London: EES.

- Depuydt, Leo., 1996. The Function of the Ebers Calendar Concordance. Orientalia, 65.2: 61-88.

- Donatelli, Laura., 2011. Lettere e documenti di Bernardino Drovetti. Turin: Accademia delle Scienze di Torino.

- Donatelli, Laura., 2016. La prima proposta d’acquisto da parte dei Savoia della collezione egizia di Bernardino Drovetti. Studi Piemontesi, 52.2: 494.

- Edwards, I E. S., 1971. The early dynastic period in Egypt. in The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge: 1-70.

- Fabretti, Ariodante., 1872. Il Museo di antichità della R. università di Torino: notizie. Turin: Stamperia reale.

- Fabretti, Ariodante, et. al., 1882. Regio Museo di Torino, Catalogo generale dei Musei di Antichità. Turin.

- Farina, Giulio,, 1938. Il Papiro dei re, restaurato. Rome: G. Bardi.

- Franke, Detlef., 1988. Zur Chronologie des Mittleren Reiches (12.- 18. Dynastie). Teil 1: Die 12. Dynastie. Orientalia, 57: 113–138.

- Franke, Detlef., 1988. Zur Chronologie des Mittleren Reiches Teil II: Die sogenannte ‘Zweite Zwischenzeit’ Altägyptens, Orientalia, 57: 245-274.

- Gardiner, Alan H., 1959. The Royal Canon of Turin. Oxford: University Press.

- Goedicke, Hans., 1956. “King HwDfA?”, JEA, 42: 50–53.

- Hartleben, Hermine., 1909. Lettres de Champollion le jeune. Paris.

- Helck, Wolfgang., 1956. Untersuchungen zu Manetho und den ägyptischen Königslisten. UGAA, 18. Berlin.

- Helck, Wolfgang., 1992. “Anmerkungen zum Turiner Königspapyrus”. SAK, 19: 151–216.

- Hincks, Edward., 1850. On the portion of the Turin book of kings which corresponds to the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties of Manetho, TRSL, 3: 128–50

- Kitchen, Kenneth A., 1979. Ramesside Inscriptions II. Oxford: 827–844 (§288)

- Krauss, Rolf., 1992. Das Kalendarium Des Papyrus Ebers und Seine Chronologische Verwertbarkeit. Egypt and the Levant, 3: 75-96.

- Lauth, Franz J., 1865. Manetho und der Turiner Königspapyrus. Munich: Wolf.

- Lepsius, Karl Richard., 1842. Auswahl der wichtigsten Urkunden des aegyptischen Alterthums. Leipzig.

- Lepsius, Karl Richard., 1853. Über die zwölfte Aegyptische Königsdynastie. APAW 1852: 425–453.

- Lesueur, Jean Baptiste Cicéron., 1848. Chronologie des Rois d’Égypte Paris: Impremerie Nationale.

- Málek, Jaromír., 1982. The Original Version of the Royal Canon of Turin, JEA , 68: 93-106.

- Maspero, Gaston., 1895. Histoire ancienne des peuples de l’orient classique. Paris.

- Meyer, Eduard., 1904. Aegyptische Chronologie. Berlin.

- Möller, Georg., 1927. Hieratiche Paläographie. Vol. 2. Osnabruck.

- Orcurti, Pier-Camillo., 1855. Catalogo illustrato dei monumenti Egizo del R. Museo di Torino. Turin.

- Redford, Donald B., 1986. Pharaonic King-lists, Annals and Day-books. Mississauga.

- Rougé, Emmanuel de., 1866. Recherches sur les monuments qu’on peut attribuer aux six premières dynasties de Manéthon. MIE, 25.2: 225–376, pl. 3.

- Ryholt, Kim., 1997. The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. Copenhagen.

- Ryholt, Kim., 2000. “The Late Old Kingdom in the Turin King-list and the Identity of Nitocris”. ZÄS, 127: 87–100.

- Ryholt, Kim., 2004. The Turin King-list, AeUL, 14: 135–155.

- Ryholt, Kim., 2008. King Seneferka in the king-lists and his position in the early dynastic period, JEH, 1: 159–73.

- Schneider, Thomas., 2006. The Relative Chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period (Dyns. 12–17). in Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies 83: 168–196.

- Seyffarth, Gustav., 1828. “Remarks upon an Egyptian History,

in Egyptian Characters, in the Royal Museum at Turin”, The London Literary Gazette, No. 600. July 19, 1828: 457–59

- Seyffarth, Gustav., 1843. Die Grundsätze der Mythologie und der alten Religionsgeschichte Leipzig: Barth.

- Seyffarth, Gustav. Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca Manuscripta, 1826-1830.

Unpublished.

- Seyffarth, Gustav, and Knortz, Karl., 1886. The literary life of Gustavus Seyffarth. New York: Steiger.

- Vidua, Carlo., 1834. Lettere del conte Carlo Vidua pubblicate da Cesare Balbo. Vol. 2. Turin: G. Pomba.

- Waddell, W. G., 1940. Manetho. 1964 Edition. Cambridge, Mass.

- Wiedemann, Alfred., 1884. Aegyptische Geshichte. Gotha: Perthes.

- Wilcken, Ulrich., 1887. Recto oder Verso? Hermes , 22: 487–492.

- Wilkinson, John Gardner., 1851. The Fragments of the Hieratic Papyrus at Turin. 2 Vols. 10 pl. London: Richards.

- Winlock, Herbert E., 1947. The rise and fall of the Middle Kingdom in Thebes. New York: Macmillan.

Note:

Many of the referenced books and journal articles

above

are available for free in the Reference Library.