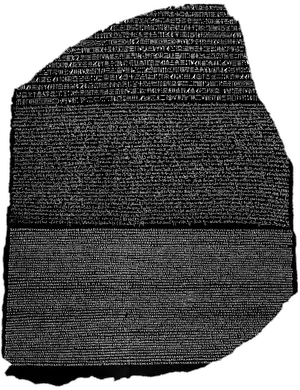

The 760 kg Rosetta Stone was unearthed in Egypt in 1799, north of the town of Rosetta, where Napoleon's soldiers were rebuilding a crumbling 15th-century fortress into Fort Julien to defend against expected Ottoman attacks.

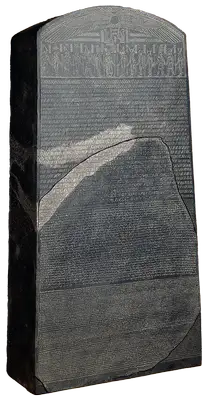

Measuring approximately 112 cm in height, 75 cm in width and 28 cm in thickness, the fragment is crafted from black granodiorite stone sourced from Aswan in Upper Egypt and represents a portion of a larger stele.

Ancient Egyptian temples were used as quarries for materials throughout Egypt’s history, and the Rosetta Stone was no exception. In the fifteenth century, it was incorporated into the foundations of a fortress constructed by the Mameluke Sultan of Egypt to defend the Bolbitine branch of the Nile at Rosetta. It remained undisturbed for three centuries until it was rediscovered by French soldiers.

The inscriptions consist of 14 lines of hieroglyphs, followed by 32 lines of Demotic and 54 lines of Greek at the bottom. None of the three texts are complete due to their damaged condition. From the moment of its discovery, the Egyptian text inscribed on the Rosetta Stone was regarded as alphabetic and closely associated with Coptic, which was believed to contain remnants of the language of ancient Egypt.

From 1800, Gabriel de La Porte du Theil, a member of the Institut National, was in charge of translating the copies brought to Paris by General Dugua. He had to abandon his work and was replaced by Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon, who presented his study to the Institute on 6 January 1801. He preferred to wait for the stone to arrive in France before publishing his results, so that he could compare them with the original, as he noticed differences in spelling between the copies. Following the defeat of the French, the stone was handed over to British control, Amheilon was more or less forced to publish Clarifications on the Greek inscription on the monument found at Rosetta, (with warnings, as he had doubts about several letters), a “very literal” translation in Latin and another, “less slavish” (in his own words), in French. It was not until 1841 that Jean-Antoine Letronne published another French version correcting Ameilhon’s errors.

The inscriptions

The inscription is a decree issued in the ninth year of the reign of Ptolemy V by a congress of priests in Memphis that established the divine cult of the new king. The precise date is specified using both the Macedonian and Egyptian calendars, and is equivalent to 27 March 196 BC.

The inscription is comprised of three distinct parts, each inscribed in a different script. However, it was only the lowermost part, written in Greek, that was legible to the scholars of the time. The language of the hieroglyphs and the Demotic was an unknown, but decipherment was thought to be almost an accomplished task.

For centuries it had been assumed that there were two distinct ancient Egyptian scripts, as told by the historians of antiquity.

“The Greeks write and calculate from left to right; the Egyptians do the opposite; yet they say that their way of writing is towards the right, and the Greek way towards the left. They [the Egyptians] use two kinds of writing; one is called sacred (From those Greek words we have hieratic and Demotic. Four centuries later (c. 50 BC), Diodorus echoed the same information in Bibliotheka 1.81:ἱρὰ , hira), the other common (δημοτικὰ , demotika)”

“In the education of their sons the priests teach them two kinds of writing, that which is called sacred (ἱερὰ , hiera) and that which is used in the more common (κοινοτέραν , koinoteran) instruction.”

“... for of the two kinds of writing which the Egyptians have, that which is known as popular (δημώδη , demodi) is learned by everyone, while that which is called sacred (ἱερὰ , hiera) is understood only by the priests of the Egyptians, who learn it from their fathers as one of the things which are not divulged.”

“Now those instructed among the Egyptians learned first of all that style of the Egyptian letters which is called Epistolographic; and second, the Hieratic, which the sacred scribes practise; and finally, and last of all, the Hieroglyphic, of which one kind which is by the first elements is literal (Kyriologic), and the other Symbolic. Of the Symbolic, one kind speaks literally by imitation, and another writes as it were figuratively; and another is quite allegorical, using certain enigmas.”

Neither author comments on the characters that make up the different scripts. However, it became increasingly clear that there were, in fact, three kinds of writing: hieroglyphs, hieratic (derived from hieroglyphs), and Demotic (a simplified form of hieratic.)

The hieroglyphs

The upper register, consisting of Egyptian hieroglyphs, has suffered the most damage. Only the last 14 lines of the hieroglyphic text are visible, all of them broken on the right and 12 on the left. It is read from right to left.

There are four complete, and two partial cartouches present in the hieroglyphic text. Two of them (numbers 2 and 3) only contain the name

The Demotic

Below this, the middle register is the best preserved, but written in a then unknown script; it has 32 lines, the first 14 of which are slightly damaged on the right. It too is read from right to left.

The intermediate text of the Rosetta Stone is written in Demotic, a previously unknown script. At the time, it was presumed that the language was ancient Egyptian and that there was a close relationship between it and Coptic. Additionally, it was assumed (incorrectly) that the texts were literal versions of each other. The relationship between hieratic and Demotic remained a topic of contention for a decade or two, with no definitive conclusion as to whether they were essentially the same or distinct.

The Greek

The lower register of the Greek text contains 54 lines, of which the first 27 are complete; the rest are increasingly fragmentary due to a diagonal break at the lower right of the stone. Unlike the other two scripts, this is read from left to right.

The decipherment

The Rosetta Stone played a pivotal role in deciphering the hieroglyphs, providing a trilingual text that opened doors that had long been closed.

Thomas Young

In his studies of the Rosetta Stone, Thomas Young noted that the cartouches contained the names of the pharaohs and had identified the name ‘Ptolemaios’.

Philae obelisk

An obelisk discovered at Philae in 1815 by William John Bankes held a bilingual Greek and hieroglyphic text with four cartouches of Ptolemy VIII (two of the throne name and two of the birth name), one of Cleopatra and one of the God Osiris. Lithographs of the obelisk was circulated in the world of the scholars. In a marginal note to some of the lithographs of the obelisk, Bankes suggested the name ‘Cleopatra’ in one of the cartouches.

Champollion

At the time of the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a little-known script had recently been found in Egypt.

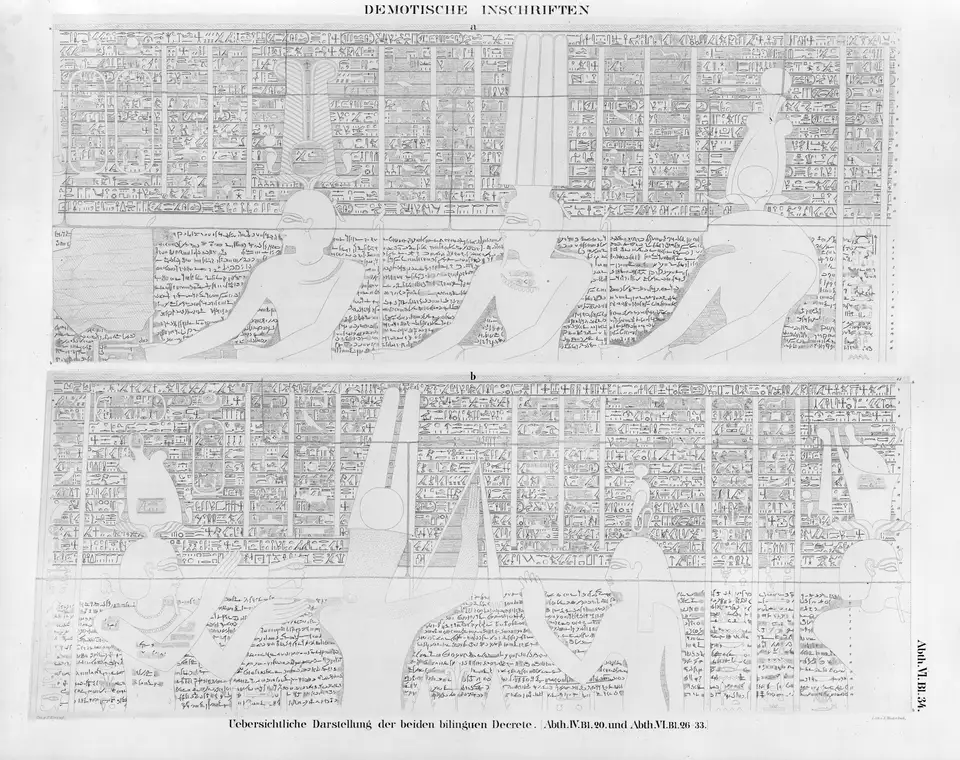

Copies of the Decree

Copies of the decree were erected in temples, two were inscribed on walls of the Philae temple of Isis, dated to Years 19 (186 BC) and 21 (184 BC). The inscriptions differed from those on the Rosetta Stone in that they added and omitted details, and they did not include the Greek text.

1

Located on the East side of the Birth House collonade. Subsequently, the decrees were overlaid with additional material, which was introduced by Ptolemy XIII Neos Dionysos. This included the partial blocking or removal of the original text. See Lepsius, Denkmaeler Hieroglyphs: IV 20. Demotic: IV 26-34. Porter and Moss, Topographical Bibliography, 6.228 (225-226).

Bibliography

- Ameilhon, Hubert Pascal. 1803. Éclaircissemens sur l'inscription grecque du monument trouvé à Rosette, contenant un décret des prêtres de l'Égypte en l'honneur de Ptolémée Épiphane, le cinquième des rois Ptolémées. Paris: Institut National.

- Commission des Sciences et des Arts. 1822. Description de l'Égypte Antiquities - Planches. Vol. 5, pls. 52-54.

- Letronne, Antoine Jean. 1840. Inscription grecque de Rosette. Paris: Firmin Didot

- Lepsius, Carl Richard. 1842. Auswahl der wichtigsten Urkunden des aegyptischen Alterthums. pls. 18-19.

- Lepsius, Carl Richard. 1866. "Das Dekret von Kanopus." Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Alterthumskunde 4. pp. 49-52.

- Lepsius, Carl Richard. 1866. Das bilingue Dekret von Kanopus. Berlin: Hertz.

- Brugsch, Heinrich. 1891. "Bautexte und Inschriften verschiedenen Inhaltes altaegyptischer Denkmaeler." Thesaurus inscriptionum Aegyptiacarum: altaegyptische Inschriften 6. p. xiv, Nos. 1554-1575. Leipzig.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. 1904. The decrees of Memphis and Canopus. The Rosetta Stone. Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 135-159.

- Quirke, Stephen; Andrews, Carol 1989. The Rosetta Stone. Abrams.

- Pope, Maurice. 1999. The Story of Decipherment, from Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script. Revised Edition. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Robinson, Andrew. 2012. Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion. Oxford University Press.

- Buchwald, Jed Z.; Josefowicz, Diane G. 2020. The Riddle of the Rosetta: How an English Polymath and a French Polyglot Discovered the Meaning of Egyptian Hieroglyphs. Princeton University Press.