This is a brief overview of some significant and influential books in the field of Egyptology. It is important to note that while the expeditions were primarily concerned with documenting sites in Egypt, they had little or no concern for their conservation.

The plundering of ancient sites, whether sanctioned or not, was the order of the day, which is how many European museums acquired their collections. It can be argued that the objects acquired by the museums were saved for posterity, as their fate would probably have been very different had they remained in Egypt, especially in the context of religious iconoclasm. Having remained undisturbed for centuries or even millennia, many of the sites explored and documented by these expeditions have since been seriously damaged by interaction with the modern world. Many historic sites can now only be visited through by way of these books, or time capsules if you will. The beautiful books produced by the three expeditions below highlighted the importance of documenting ancient sites in great detail, ultimately giving rise to modern archaeology.

Napoleon’s Expedition (1798–1801)

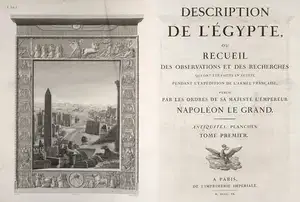

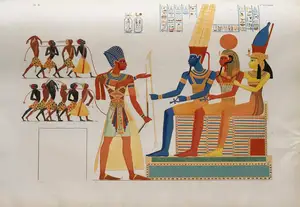

Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1798 campaign in the Ottoman territories of Egypt and Syria, intended to protect French trade interest and hinder British commerce. An unusual aspect of the Egyptian expedition was the inclusion of a contingent of 167 scientists and scholars ("the savants"). This deployment of intellectual resources was a masterstroke of propaganda obfuscating and hiding its true motives. The expedition led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, which led to the decipherment of the hieroglyphs and was the first step towards the creation of the field of Egyptology. After Napoleon's defeat in 1801, the stone, and other antiquities discovered by the French, became British property under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria.Of particular interest are the five volumes of drawings and paintings of the tombs, monuments and artefacts from antiquity, published in large folio format in the following decades as part of Description de l’Égypte. The majority of the monuments, temples, and tombs had long since fallen into ruin. Many had been buried in sand or mud for centuries or even millennia, which, combined with the arid conditions prevalent in the Nile Valley, had helped to preserve the inscriptions and paintings from being weathered. In the early days of excavation in Egypt, the work was largely undertaken by adventurers seeking to uncover treasure. Over time, however, archaeology emerged as a distinct discipline, with the objective of uncovering artefacts. Hieroglyphs were not copied accurately by the artists because they were not yet understood to represent a language. The plates continue to be an important time capsule and, in some cases, the only source because of the subsequent deterioration or even destruction that occurred after their discovery.

The Description contains more than 20 volumes in total, some dedicated to flora and wildlife, others to modern Egypt, but most importantly, five volumes on Ancient Egypt, with detailed maps and rich illustrations of ruins, tombs, monuments, temples and other Egyptian artefacts like scarabs, papyri and even mummies.

5 volumes, 423 plates

- Volume 1 — 100 plates.

- Volume 2 — 92 plates.

- Volume 3 — 69 plates.

- Volume 4 — 73 plates.

- Volume 5 — 89 plates.

Franco-Tuscan Expedition (1828-1829)

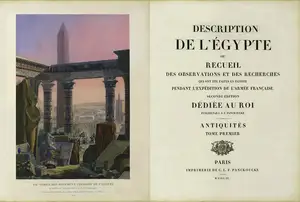

When examining hieroglyphic and hieratic texts and comparing them with his own eyes to the drawings provided to him, Jean-Francois Champollion noted that there were a plethora of errors and omissions in the copies. Celebrated throughout the world for deciphering the hieroglyphs, his fame finally afforded him to visit Egypt as part of the Franco-Tuscan Expedition surveying Egypt in 1828-1829. Headed by Champollion and assisted by Rosellini, the mission was made possible by the support of the grand-duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, and the French king Charles X. The expedition was much smaller then Napoleon's, consisting of a team of eleven Frenchmen and Italians.The notes and drawings of the expedition were collected in Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia by Rosellini and in Monuments de l’Egypte et de la Nubie by Champollion, published posthumously by his brother, Champollion-Figeac. The accuracy of the hieroglyphics were much improved compared to the Napoleonic expedition, though still with many errors.

9 volumes of text + 390 plates.

- Volume 4.1 (1832) — 169 plates.

- Volume 4.2 (1834) — 135 plates.

- Volume 4.3 (1844) — 86 plates.

2 volumes of notes + 509 plates

- Volume 1 (1835) — 112 plates.

- Volume 2 (1845) — 121 plates.

- Volume 3 (1845) — 109 plates.

- Volume 4 (1845) — 167 plates.

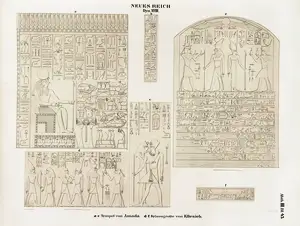

Prussian Expedition (1842-1845)

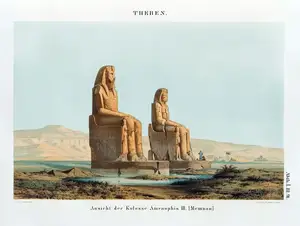

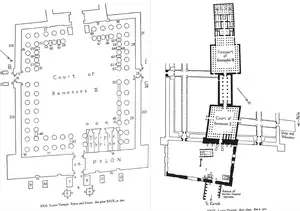

In 1842 Emperor Friederich Wilhelm IV of Prussia commissioned Karl Lepsius to lead a scientific expedition to Egypt to record the monuments. The expedition visited sites along the Nile, both known and previously unknown, resulting in the large format Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien (Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia), a scientifically based set of volumes containing rubbings and very detailed drawings and maps. Unlike most of the previous expeditions, Lepsius had the hierioglyphic contents of the monuments meticulously copied. There are still some errors, but mostly minor ones. The drawings made by the expedition are almost invariably superior to those made by others, and they are made with the level of detail that modern Egyptologists presume. This is apparent by the fact that they are still relevant almost two centuries later.- Richard Lepsius (1810–1884), Egyptologist, leader of the expedition

- Georg Erbkam (1811–1876), architect

- Johann Jakob Frey (1813–1865), painter, became too sick to paint

- Friedrich Otto Georgi (1819–1874), draftsman replacing Frey

- Ernst Weidenbach (1818–1882), draftsman

- Joseph Bonomi the Younger (1796–1878), draftsman (English)

- Maximilian Ferdinand Weidenbach (1823–1890), draftsman

- James William Wild (1814–1892), architect (English)

- Carl Franke, plaster molder

- Heinrich Abeken (1809–1872), theologian and diplomat

- October 1842 to May 1843 – Memphis (Giza, Saqqara, Memphis etc.)

- Spring 1843 – Fayuum (three months)

- Summer 1843 to summer 1844 – Middle and Upper Egypt, and Nubia

- November 1844 to May 1845 – Thebes region

- Summer 1845 – Sinai peninsula

The expedition brought back thousands of sketches and drawings of the landscapes, monuments, tombs and much more. The architectural and topographical drawings and site plans seriously improved and basically invented the standard for archaeology. As it was ordered by the emperor, the publication had to be of the utmost quality, and from the more than 2000 large illustrated sheets, 957 were selected for publication in the large-sized atlas folio volumes. The first volume appeared in 1849, and the rest followed over the next decade, though none of the volumes are dated.

12 volumes, 894 plates, + 63 in Supplement

- Section I — 145 plates. Maps, topography, landscapes. (Volumes 1-2)

- Section II — 153 plates. Old and Middle Kingdom (Volumes 3-4)

- Section III — 304 plates. New Kingdom up to the second Persian conquest. (Volumes 5-8)

- Section IV — 90 plates. Persian, Ptolemaic and Roman times. (Volume 9)

- Section V — 75 plates. Nubia. (Volume 10)

- Section VI — 127 plates. Other inscriptions, i.e. Hieratic, Demotic, etc. (Volumes 11-12)

- Supplement — 63 plates. Other inscriptions (Hieratic, Demotic, etc.) This final volume of plates was compiled by Adolf Erman in 1913.

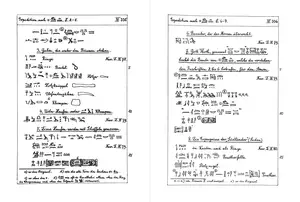

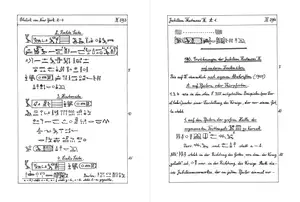

- Text — 5 volumes. Handwritten text, notes and drawings further describing the visited sites. The five volumes of Lepsius’s texts appeared after his death, in 1884, when Edouard Naville, Ludwig Borchardt, and Kurt Sethe compiled his notes for publication.

Topographical Bibliography

There is one book series in Egyptology that is essential for everyone studying ancient Egypt: a vast index of ancient Egyptian things simply known as Porter & Moss. Bertha Porter and Rosalind Moss' Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings, is the reference of references in Egyptology. If you are looking for references and/or information about a temple, a site, a monument, or an artifact, this is most likely where you will find it.The first seven volumes list ancient Egyptian monuments still in situ in Egypt. It includes items found in excavations, and most importantly, also lists the exact books where the findings were first published.

Systematic records of excavations in Egypt began in the 1860s, but digging for monuments had been going on for at least half a century before that. There are enormous numbers of objects of unknown provenance, including some of great importance found at museums all over the world. These can be found in the eighth volume.

- I. Theban Necropolis

- 1. Private Tombs

- 2. Royal Tombs and Smaller Cemeteries

- II. Theban Temples

- III. Memphis

- 1. Abu Rawash to Abusir

- 2. Saqqara to Dahshur

- IV. Lower and Middle Egypt

- V. Upper Egypt. Sites

- VI. Upper Egypt. Chief Temples

- VII. Nubia, The Deserts and Outside Egypt

- VIII. Objects of Provenance Not Known

- 1. Royal Statues. Private Statues (Predynastic to Dynasty XVII)

- 2. Private Statues (Dynasty XVIII to the Roman Period). Statues of Deities

- 3 Objects of Provenance Not Known. Part 3. Stelae (Predynastic to Dynasty XVII)

- 4 Objects of Provenance Not Known. Part 4. Stelae (Dynasty XVIII to the Roman Period)

- x Objects of Provenance Not Known. Indices to Parts 1 & 2. Statues

All volumes are available online at the Griffith Institute.

Catalogue Général

Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire

( General Catalogue of Egyptian Antiquities in the Cairo Museum )

The Cairo Museum Journal d'Entrée (abbreviated JE or JdE) describe over 100,000 registered artefacts; in theory, all things excavated or discovered were numbered when they first arrived at the Museum. In the late 1850s, Auguste Mariette began maintaining these handwritten records to keep track of the inventory at the Museum at Bulaq. The Journal d'Entrée remains the starting point for much more elaborate research.

The Catalogue Général (abbreviated CG) is a collection of items originating in Ancient Egypt. Several of the Museum's items appear in more than one volume of the Catalogue, and in rare circumstances, the same number has even been assigned to different objects. The Catalogue provides detailed information about the item and its content, frequently including sketches of the scenes represented on the object and transcriptions of the hieroglyphs. These books are now very old and rare.

Ancient Egyptian objects registered at the Museum are commonly referred to by one or both designations; for example, the Saqqara Canon is most commonly referred to as JE 11335, but sometimes as CG 34516.

Urkunden des aegyptischen Altertums

German for Documents of Egyptian antiquity

Urkunden is a major German collection of mostly handwritten publications in the field of Egyptology, focusing on the documentation and publication of transcribed ancient Egyptian royal inscriptions, funerary texts, religious texts, legal documents, and more. It is commonly abbreviated simply as Urk., or Urkunden. The inscriptions also include many other archaeological artefacts. This series has played a crucial role in making various ancient Egyptian documents and texts available to scholars and researchers.

The series includes numerous volumes, each of which is dedicated to a specific set of inscriptions, texts, or documents. These volumes are typically authored or edited by Egyptologists and experts in the field. It was published between 1903 and 1961 and is organised into eight sections, each with several volumes.

- Urkunden des Alten Reichs (Old Kingdom)

- Hieroglyphische Urkunden der Griechisch-Römischen Zeit (Greek and Roman periods)

- Urkunden der Älteren Athiopenkönige (Nubian Dynasty), ed. Schäfer 1905

- Urkunden der 18. Dynastie (18th Dynasty), ed. Helck 1955–1958

- Religiöse Urkunden (religious texts)

- Urkunden Mythologischen Inhalts (mythological texts)

- Urkunden des Mittleren Reiches (Middle Kingdom)

- Historisch-biographische Urkunden der Zeit zwischen AR u. MR. (FIP)

Referenceing is made using the following terms: Urk. <section, page> (Urk. IV, 1369) refers to Section 4, page 1369, which is found in Volume 18 – the volume number is always omitted.

Ramesside Inscriptions

The series was written by Kenneth A. Kitchen, a distinguished Egyptologist known for his expertise in the history and hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt. This comprehensive and influential series of books compiles, transcribes and translates inscriptions and texts from the later part of the New Kingdom period of ancient Egypt, particularly those associated with the Ramesside pharaohs (including Ramesses II and his successors) of the Nineteenth and Twentieth dynasties. This work is often referenced by the first series as KRI <volume, page> (i.e. KRI VII, 363).

Ramesside Inscriptions : Historical and Biographical [RIHB]:

- RIHB. Volume I. Ramesses I, Sethos I, and Contemporaries. Oxford, Blackwell, 1975

- RIHB. Volume II. Ramesses II. Royal inscriptions. Oxford, Blackwell, 1979

- RIHB. Volume III. Ramesses II, His Contemporaries. Oxford, Blackwell, 1980

- RIHB. Volume IV. Merenptah and the Late Nineteenth Dynasty. Oxford, Blackwell, 1982

- RIHB. Volume V. Setnakht, Ramesses III and Contemporaries. Oxford, Blackwell, 1983

- RIHB. Volume VI. Ramesses IV to XI and Contemporaries. Oxford, Blackwell, 1983

- RIHB. Volume VII. Addenda and indexes. Oxford, Blackwell, 1989

- RIHB. Volume VIII. Indexes. Oxford, Blackwell, 1990

- RIBH. Volume IX. Documents. Joshua Aaron Roberson. Wallasey, Abercromby Press, 2018

Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated [RITA]:

- RITA: Translations. Volume I. Ramesses I, Sethos I, and Contemporaries. Oxford-Cambridge (MA), Blackwell, 1993

- RITA: Translations. Volume II. Ramesses II. Royal inscriptions. Oxford-Cambridge (MA), Blackwell, 1996

- RITA: Translations. Volume III. Ramesses II, His Contemporaries. Oxford-Malden (MA), Blackwell, 2000

- RITA: Translations. Volume IV. Merenptah and the Late Nineteenth Dynasty. Malden (MA)-Oxford, Blackwell, 2003

- RITA: Translations. Volume V. Setnakht, Ramesses III and Contemporaries. Malden (MA)-Oxford, Blackwell, 2008

- RITA: Translations. Volume VI. Ramesses IV to XI and contemporaries. Chichester - Maldon (MA), Willey-Blackwell, 2012

Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Notes and Comments [RITANC]:

- RITANC. Volume I. Ramesses I, Sethos I, and Contemporaries. Oxford-Cambridge (MA), Blackwell Publishers, 1993

- RITANC. Volume II. Ramesses II. Royal inscriptions. Oxford-Cambridge (MA), Blackwell Publishers, 1999

Other

A number of other series exist, but these are the largest and most significant, but despite being written quite some time ago, they are still of use to this day.