In the early Ptolemaic Kingdom (3rd century BC), Manetho, an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos, wrote

Often Latinised as Aegyptiaca, it has been of great interest to historians since ancient times and has played a pivotal role in establishing the chronology of ancient Egypt. The concept of dynasties–which groups together a succession of rulers on the basis of family–originated with Aegyptiaca and remains in use today. It has been instrumental in dividing the lengthy history of Egypt into more manageable periods.

The date of composition of Aegyptiaca is estimated to be between 300 and 250 BC. However, the absence of any contemporary records makes it

impossible to determine with certainty whether Manetho wrote it during the reign of Ptolemy I, Ptolemy II or Ptolemy III. The traditional dynasties of Manetho used in conjunction with the existing archaeological records, provide Egyptology with the basic chronology of ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, the

reliance on Manetho to reconstruct the Egyptian dynasties is inherently problematic, given that the original text was lost in antiquity and replaced

by summaries. It was Syncellus, in the ninth century, who identified the parallels, mainly in

the works of Africanus and Eusebius, and

assembled excerpts from their work.

Scholars have long tried to reconcile Manetho's work with the archaeological evidence. While there are many points of agreement, it is clear that his original account was significantly altered by the transcription of Egyptian names into their Greek equivalents. The accounts of Africanus and Eusebius differ from those of Josephus, who presented Manetho's text as a narrative over a century earlier rather than just a list of kings. It is reasonable to assume that non-Egyptian copyists of epitomes in subsequent centuries would also have struggled with the strange-looking Egyptian names. The chronological tables of Eusebius were preserved in Jerome's Chronicle, which was not mentioned by Syncellus.

Despite this, the importance of Manetho cannot be understated as it was—and to some extent still is—the primary source for the chronology of the pharaohs. The names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra played a central role in the process of deciphering the hieroglyphs, and one of the first things Champollion did after deciphering the hieroglyphs was to compare the now-readable names of the pharaohs with those of Manetho.

The sources used by Manetho

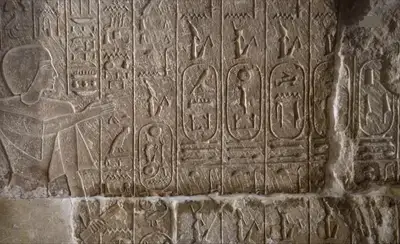

The ancient Egyptian king-lists were inscribed on the walls of a sacred room, making offerings to celebrated ancestors. The purpose of these lists was not to make a necessarily accurate chronological list of historical kings but to celebrate revered ancestors for religious or political reasons. Seti I deliberately excluded Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Hatshepsut from his king list at Abydos, as their reigns were considered illegitimate or heretical, and they were to be erased from memory.

Manetho could not have based his history solely on the Abydos and Karnak inscriptions, as these differ from one another and only contain the names of carefully selected kings. Therefore, they cannot be accurate chronological records. His source was most likely something similar to the Turin King List, which contains detailed accounts from the time of the gods up to the 3rd century BC. It seems that all kings, regardless of how briefly they reigned or how despised they were, are included in this list.

Even the most ephemeral of kings is highly likely to have left behind records that could be discovered long after their time by a devoted priest who knew where to look. Important documents were certainly copied repeatedly throughout the centuries. However, the vast expanse of time is not kind to fragile papyrus records, which were susceptible to destruction by fire, flood and countless other forces.

As a priest, Manetho would have had access

to virtually all of Egypt's written records. There were probably sources unknown to us, but the transcribed names were not consistently chosen

from the same type of name. The reason for this is unclear, but it is plausible that the original document contained multiple names for each

king, which would have caused confusion for a non-native epitomist who was unaware of this fact. In some cases, transcription is possible; in

others, consonants switched places for unknown reasons, perhaps due to transcription errors by the epitomists.

As a priest, Manetho would have had access

to virtually all of Egypt's written records. There were probably sources unknown to us, but the transcribed names were not consistently chosen

from the same type of name. The reason for this is unclear, but it is plausible that the original document contained multiple names for each

king, which would have caused confusion for a non-native epitomist who was unaware of this fact. In some cases, transcription is possible; in

others, consonants switched places for unknown reasons, perhaps due to transcription errors by the epitomists.

Many of the names of the pharaohs, as recorded by Manetho, are still in use today and were favoured until the discovery and corroboration of the original king lists. Using the original names of the pharaohs is still a relatively new practice.

Epitomes

An epitome is a condensed version of a larger work, highlighting selected key points, passages, or arguments while omitting less relevant sections. Often created by or at the behest of the original author, epitomes were used for specific purposes, such as providing quick access to information or to tailor content to potential readers. However, they often raise concerns about fidelity to the original, as the choice of what to include or omit could lead to misrepresentation or distortion.

Copyists played a significant role in creating epitomes, selecting details they deemed important and discarding others. Misunderstanding the source could result in omitting crucial elements or introducing errors. Sometimes, additional material from other sources was incorporated to align with the copyist's intentions.

In antiquity, epitomes were popular due to the cost-effective reproduction process, where texts could be read aloud to multiple scribes transcribing simultaneously. However, this method risked errors accumulating over generations of manuscripts unless strict quality checks were applied, which was both difficult and uncommon.

It is unclear whether Manetho himself created an epitome of Aegyptiaca. In the centuries after his time, Jewish historians took great interest in due to its relevance to their ancestral ties with Egypt—such as Abraham, Joseph, Moses, and the Exodus. They aimed to use Egyptian traditions to support the origins and antiquity of the Jewish people. However, they encountered an unfavorable claim in Aegyptiaca suggesting that the Jews descended from lepers. Jewish apologists likely created their own epitome of Aegyptiaca, reshaping the text to highlight their history in a more favorable light while removing or modifying parts they found unfavorable. This, of course, altered Manetho's original text and the result may be seen in Josephus' treatise Contra Apion I (§§227-230):

227 The first person on whom I shall dwell in my discussion I employed a little earlier also as a witness to our antiquity.228 That is Manetho, who undertook to translate the history of Egypt from the sacred writings, and says first that our ancestors came against Egypt in very large numbers and ruled the inhabitants, then himself admits that at a later date again they were thrown out, occupied present-day Judea, founded Jerusalem, and built the sanctuary. Up to this point he followed the records.229 But then, giving himself license by saying he would record myths and rumors about the Judeans, he inserted implausible stories, in the desire to mix up with us a crowd of Egyptian lepers and people who for other diseases had been, he says, condemned to exile from Egypt.230 Having put forward a king Amenophis, a made-up name and hence not daring to fix the duration of his reign (although he accurately appends dates to the other kings), he connects him with certain myths, no doubt forgetting that he had recorded the exodus of the shepherds to Jerusalem as taking place years earlier.

The extent of the narrative in Aegyptiaca is uncertain, while it is possible that it was simply a brief list of kings with a few comments where needed, the excerpt by Josephus suggests that it was more substantial.

Transmission of Manetho

The surviving text of Manetho’s Aegyptiaca can only be traced back to The Chronicle by Syncellus, written around 808-810. Multiple copies

of the original Chronicle have survived. It was not until Manuscript A was discovered around 1600 and published by Scaliger in 1606 that Syncellus’s

Chronicle became known. It is worth noting that Scaliger only included selected passages. After almost five decades, Jacob Goar published the first

all-inclusive edition of Syncellus in 1652. While Manuscript B was discovered shortly afterwards, it remained undisclosed and unpublished

for many years. In 1829, Dindorf utilised this second manuscript to rectify readings in Goar’s edition. Until the publication of the Mosshammer edition

in 1983, it was deemed the standard edition.

A and B are complete copies and share a common ancestor. Although few incomplete copies of

Syncellus exist, A and B are the only ones containing the texts of Manetho (through Africanus and Eusebius).

It seems clear that following the introduction of Aegyptiaca, an epitome was composed of extracts from the dynasties of kings, with additions and alterations to make it fit with Jewish chronology. It should also be noted that the epitome(s) were not produced by the author but rather by persons who could indiscriminately alter, add or remove things to them in order to advance their own interests. In all likelihood, numerous quite different copies of Aegyptiaca circulated in the centuries after Manetho. Epitomists may have attempted to preserve the spirit of the original, but as with all secondary sources, a different bias may be introduced, along with the addition of details or anecdotes not present in the original. It also works in the other direction, as important facts may have been changed or omitted, whether by design or error, or both.

In antiquity, authors wrote all their books by hand. Each text was a unique original, and if someone wanted to read it, they either borrowed it or had a copy made by a scribe. Written works did not spread particularly quickly; however, the educated, literate class was relatively small, and only a few copies were needed to be written for the work to become well-known by the elite. A significant number of works were epitomised, which entailed the creation of a brief summary of the original that often included extracts from the original text The skill of the scribe writing the epitome could influence the intended meaning and impact of the original text.

It is a well-established fact that each copy of a handwritten document introduces errors through various means, whether intentional or unintentional. Human error represents a significant factor contributing to the potential corruption of handwritten manuscripts. Scribes, who were responsible for copying texts in ancient times, were highly skilled individuals. However, they were not immune to mistakes, and their linguistic skills varied, especially in relation to the nuances of foreign languages, which could be problematic and cause their own corruptions.

It is therefore crucial for scholars engaged in textual criticism, a field that aims to reconstruct the most accurate version of a text by comparing different manuscript copies and identifying variations, to understand the potential for human error. This process helps researchers discern the original wording and meaning of a text despite the inevitable errors introduced by scribes throughout history. It is also important to remember that each copy introduced more corruption of the original.

It seems reasonable to assume that there must have been several exemplars of Aegyptiaca in circulation during antiquity, as evidenced by the variations observed in the sources below. It is impossible to ascertain to what extent these epitomes included the original text.

Simplified, here’s how Aegyptiaca reached us (Fig. 1):

Fig 1. Transmission of Aegyptiaca. Dashed borders = lost manuscript.

The information provided for each dynasty will take into account all the different sources. Timekeeping in the ancient world was confounded by the fact that each city-state employed its own calendar for when a year begin. Since there was no single calendar in use, events were primarily dated by the regnal year of the locally reigning monarch.

Lists of kings and the number of years they reigned were certainly circulated, but kings did not always ascend to the throne on January 1st, and records might be emended or corrupted in numerous ways. As a result, any reckoning based on regnal years was likely to be inaccurate, perhaps significantly so, as errors accumulated.

- Manetho — 275 BCE +/- 30 years

-

Manetho flourished in the time of Ptolemy I (305–282 BC), Ptolemy II (285–246 BC), or Ptolemy III (246–222). The original Aegyptiaca papyrus was lost in antiquity and we can only guess at its full contents. There are clues from other authors, but they all wrote several centuries later

and had to rely on abridged versions of the original text, called epitomes. There is no way of judging what information was copied and what was

left out by the epitome author. It is even possible that Manetho himself made an epitome of his original, a common practice in antiquity.

Africanus and Eusebius say that Aegyptiaca was written in three volumes - but this could easily have been for the epitome version. Josephus does not give a number of volumes. The original Aegyptiaca may have been 10 or 20 volumes for all we know.

In the subsequent centuries, Aegyptiaca was replaced by Epitomes (summaries) from rivalling advocates of Jewish, Egyptian, and Greek history, that saw each side trying to establish the truth—according to their point of view. It is unclear and impossible to assess to what extent the epitomes preserved Manetho’s original writing. Whether by intention or by accident, each subsequent copy undoubtedly introduced some corruption of the original, whether by scribal errors, outright alterations, or other mutilations made in order to advance one of the many conflicting agendas. It is apparent that none of the authors whose works have survived had access to the original Aegyptiaca, only epitomes.

Furthermore, as only excerpts from the epitomes survive from the ancient historians, we have only indirect knowledge of Aegyptiaca, and chances are that errors multiplied with each successive copy, as seen by the discrepancies in the extracts referenced by later authors. This means that the names we know from Africanus and others are probably very different from Manetho’s original in many cases.

Vol. 1 Dynasties 1-11 : Reign of the gods and spirits to the historical kings.

Vol. 2 Dynasties 12–19 : From the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom.

Vol. 3 Dynasties 20-31 : From the collapse of the New Kingdom to Alexander the Great.

The transcription of Egyptian names into Greek would be problematic for a non-native Egyptian copyist, who would also find Manetho’s headings and summaries exceedingly confusing because some of them included not only multiple kings with the same name but perhaps also coregencies and even the–at the time–unseemly mention of queens. - Josephus — four centuries after Manetho (c. 95 CE)

- The oldest surviving mention of Manetho comes from Flavius Josephus writing in the last decade of the first century. In the Antiquities of the Jews, and Against Apion he quotes from “the Egyptian born Manetho who translated Egyptian history from the priestly writings.” He acknowledged that he used an epitome of Aegyptiaca, and his excerpt suggest that Aegyptiaca was, at least in part, composed as a narrative rather than just a list of dynastic kings with occasionally inserted anecdotes or events. Furthermore, Josephus makes no mention of any dynastic divisions. He identifies only 25 pharaohs, most of them from the New Kingdom, but notably, this encompasses two queens.

- Africanus — five centuries after Manetho (c. 220 CE)

- Julius Africanus (c. 160–240 CE) was an early Greek Christian historian. He wrote Chronographiai, a history of the world in five volumes; from the birth of the Adam to his own time. The original has not survived, it is only known in fragments, primarily excerpts preserved by Eusebius and Syncellus.

- Eusebius — six centuries after Manetho (c. 325 CE)

- Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260–339 CE), was an early Greek Christian historian influenced by Africanus.

He wrote his Chronicle c. 310 CE, which is a two-volume “Universal History” from the birth of Abraham up his own time. The original volumes

in Greek are lost, but quotations preserved by later authors makes it possible to reconstruct most of it.

The first volume, The Chronography, is only preserved as an Armenian translation of the original Greek text. It begins with an introduction, then briefly describes how various ancient Mediterranean civilisations kept time, and includes lists of their rulers. The information is excerpted, with occasional comment and criticism, from a variety of sources. There are chronological regnal lists of the Chaldeans, Assyrians, Medes, Persians, Lydians, Hebrews, Egyptians, Athenians, Argives, Sicyonians, Lacedaemonians, Corinthians, Thessalians, Macedonians, and Romans.

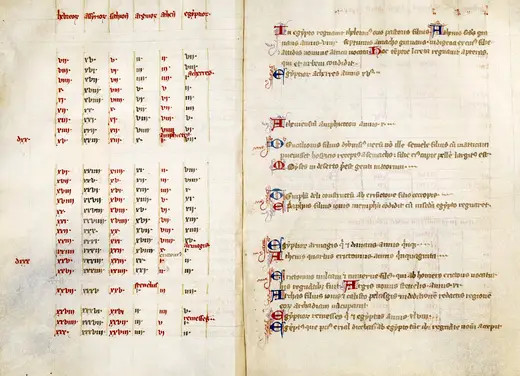

The second volume, the Chronological Canons, revolutionised the study of history. Using the relatively new codex medium, Eusebius divided up the two-page spread of the facing pages in vertical columns. He labeled the leftmost section ‘Kings of …’ (whichever empire was in power at the time), and the rightmost section ‘Kings of the Egyptians’. When new powers arose, he added an extra column to accommodate them; when they disappeared, the column vanished as well. When a king took the throne, his name was recorded on a separate line, and then listed each year of his reign on successive lines with enough space for additional information if needed.

An updated Latin translation of the Canons known as the Chronicle of Jerome was created by Jerome of Stridon around 382. The purpose of the work as a whole was partly to make clear the greater antiquity of Hebrew history relative to most others. Jerome's Latin translation proved popular and quickly became the widely accepted chronographic standard.

Eusebius does not begin the Chronological Canons with the first king of Egypt, but rather with the year Abraham was born, which he places exactly at the start of the Theban Sixteenth Dynasty. While his predecessors attempted to calculate the date of creation, Eusebius regarded Abraham to be the most ancient figure whose chronology could be established with reasonable certainty. To prove the greater antiquity of Hebrew history, he needed to link information from Jewish and Greek sources, to be able to synchronise chronological details about kings and events from different kingdoms. This new innovation of Eusebius, made it easy to compare who was in power where at any given time. We can never confirm the accuracy of chronological events so long ago, but at least we have a starting point and can try to fill in the gaps.

He collected information from a wide range of authors who did not use a common chronographic system. Among the sources used, we find Eratosthenes of Cyrene, Apollodorus of Alexandria, Castor of Rhodes, Porphyry of Tyre, Sextus Julius Africanus, Clement of Alexandria, Tatian, and an unidentified Olympiad chronicle, but also the Bible, the Canon of Kings, and of course, Manetho.The Chronicle of Jerome manuscripts

- O Oxford Bodleian Lat. Auct. T. II. 26

Fifth century — written in a late fifth-century Italian uncial; f. 1-32 supply the beginning of the work in a fifteenth-century hand.

- S Floriacensis fragments

Fifth century — Three fragments of an Italian uncial manuscript which was still intact in the ninth century at the Fleury Abbey near Orleans in France.

(i) 6 pages in Leiden Vossius Lat. Q 110A.

(ii) 14 pages of Paris Bibliothèque Nationale Lat. 6400 B.

(iii) 2 pages of Vatican Reg. Lat. 1709 B (fol. 34-35). - B Bern 219

Ninth century. Complete Chronicle and well preserved, possibly written at the famous Benedictine library at Fleury Abbey near Orléans.

- A Amandinus Valentianus 495

Seventh century. Uncial. Complete copy from the monastery of Saint-Amand Abbey near Valenciennes in northern France. Descendant of S.

- O and S were likely copied from the same manuscript. There are currently

more than a hundred manuscripts of the Chronicle of Jerome, many also include the chronicles of medieval continuators:

Berlin Staatsbibliothek Phillipps 1829 and 1872

London British Library MS Add. 16974

Leiden Scaliger 14

Leiden Vossius Lat. Q 110 (Petavianus)

Lucca Biblioteca Capitolare Feliniana 490

Oxford Merton College 315 - (transl. pt 1 pt 2)

Paris Bibliothèque Nationale Lat. 4858, 4859, 4860, and 4870

- O Oxford Bodleian Lat. Auct. T. II. 26

- Syncellus — more than 1,000 years after Manetho (c. 810 CE)

- Selected Chronography, a chronicle written

by Byzantine George Syncellus, is the primary source of our knowledge of the contents of

Aegyptiaca, thanks to Syncellus' preserved excerpts from Africanus and Eusebius' chronicles. The original manuscript of Syncellus has been

lost, and only later copies remain.

The chronicle itself was unknown until Manuscript A was discovered around 1600, and published by Scaliger in 1606. Scaliger only included selected passages, but in 1652 the first complete edition of Syncellus was published by Jacob Goar. A few years later, the superior Manuscript B was discovered, but remained unknown and unpublished until 1829, when Dindorf used this second manuscript to correct readings in Goar’s edition.- A - Codex Parisinus Bibl. Nat. Gr. 1711

- 11th century — Pages 1-230 — Contain the entire work of George Syncellus, with one leaf lost. The copyist wrote in very small letters, with many abridgements, so that the forty-one lines on each page contained as much text as two pages of another codex, or five pages of the original family of books containing the latter part. the scribe worked hastily, distinguishing little between the prescriptions and the text, paying little attention to orthographical matters, often omitting words and lines, but infrequently restoring them in the margin, frequently misreading the readings and seldom correcting them. The damage is so painful that, apart from this codex and its signature, no manuscript book of the entire work exists almost intact

- B - Codex Parisinus Bibl. Nat. Gr. 1764

- 11th century — Pages 1-143 — Written at about the same time, or perhaps a little before codex A, this book was drawn up in the same place, from the same copy, and this codex is far superior because of the reliability of the transcription, in orthographic matters, sometimes in the order of writing, but especially in the chronography. With twenty-nine lines, the page is not as congested as in codex A. The prescriptions, especially those that prescribe the years of the world, stand on their own line in capital characters, occasionally marked by red ink, and occasionally written in big calligraphic letters.

While there are a few other incomplete copies of Syncellus’ chronicle, only MSS A and MSS B contain the texts of Manetho. Syncellus also presented information about the Old Chronicle and the Book of Sothis.

Pseudo-Manetho

Pseudo-Manetho is a term used to describe manuscripts that are claimed to be written by Manetho but are actually forgeries created by subsequent authors who used Manetho's name to attempt to give forgery credibility.

- Old Chronicle — eight (?) centuries after Manetho (c. 400)

- Syncellus: “Now, among the Egyptians there is current an old chronography, by which indeed, I believe, Manetho has been led into error. In 30 dynasties with 113 generations, it comprises an immense period of time [not the same as Manetho gives] in 36,525 years, dealing first with the Aeritae, next with the Mestraei, and thirdly with the Egyptians.” [All three merely refers to Egypt at different times. The actual total is 36,347 years.]

- Book of Sothis — eight centuries after Manetho (c. 400)

- Also called the Sothic Cycle, Syncellus attributed it to Manetho but it is most likely a forgery used/composed by Panodorus of Alexandria. The sequence of kings is clearly not presented in chronological order.

- Eratosthenes — c. 50 years after Manetho

- According to Syncellus, Apollodoros of Athens (second century BC) recorded a list of 38 Theban kings taken from Eratosthenes of Cyrene (third century BC), Chief Librarian at the Library of Alexandria from 240 BC. However, both authors are considered pseudonymous, i.e. written by someone else, using their names to lend authority to the list. Some names can also be found in Manetho and Herodotus, but some have no resemblance to other known lists indicating that the list was corrupted by an intermediary, or invented.

Fragmentary comments

Often attributed to include fragments of Manetho, but most are short isolated passages, often unrelated to Aegyptiaca content.

- Plutarch — three centuries after Manetho (c. 70-85? AD)

- Plutarch references Manetho multiple times in Isis and Osiris; however, it is unlikely that the source was Aegyptiaca, but rather another work by Manetho. Plutarch visited Alexandria and Egypt to complete his education, and although it is unknown when he wrote the essay, it is generally thought to have been after his visit to Egypt.

- Excerpta Latina Barbari — eight centuries after Manetho (c. 500)

- This little chronicle was probably written in Greek around 500 AD and later translated into Latin by the eponymous 'barbarian', who had only a rudimentary knowledge of both languages. The only kings of Egypt mentioned are those of the Ptolemaic Dynasty – which were not included by Manetho.

- Malalas — nine centuries after Manetho (c. 550)

- Drawing on Eusebius and other compilers, Ioannes Malalas, a Byzantine chronicler from Antioch, wrote a Chronographia in 18 books. He mentions Manetho in two places: These ancient reigns of early Egyptian kings are recorded by Manetho... and the ancient reigns in Egypt before King Naracho were set forth by the wise Manetho, as has already been mentioned. Malalas presented precisely nothing from Manetho, he just referenced his work.

After Manetho

The pharaohs that ruled after the conquest by Alexander the Great, are not mentioned by Manetho. As Syncellus put it more than a thousand years after Manetho:

Extending up to the time of Ochos and Nektanebo, Manetho's outline of the thirty-one dynasties of Egypt encompassed a period of 1050 years for his third book. But the sequence of years after this is taken from Greek historians. There are fifteen Macedonian kings.

Bibliography

- Adler, W. and Tuffin, P., 2002. The Chronography of George Synkellos. Oxford

- Barclay, John M. G., 2007. Against Apion (vol. 10 of Flavius Josephus: translantion and commentary. Leiden.

- Dindorf, W., 1829. Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae. Bonn.

- Goar, J., 1652. Georgii Monachi quondam Syncelli Chronographia. Paris.

- Mosshammer, A. A., 1984. Georgii Syncelli Ecloga Chronographica. Leipzig.

- Scaliger, J. J., 1606. Thesaurus Temporum. Leiden.

- Waddell, W. G., 1964. Manetho. Cambridge, Mass;London.

- Verbrugghe, G. P. & Wickersham, J. M., 1996. Berossos and Manetho, introduced and translated. Ann Arbor.