Although there is consensus among scholars regarding the fundamental sequence of major chronological periods in ancient Egypt, the precise dates and relationships remain a matter of ongoing research and debate.

Introduction

Ancient records are often a singular reference without any other verifiable source. The provided information is basically all that have survived, making the reliability questionable. Some sort of calendar became essential to anticipate the seasons and planning planting and harvesting of crops. Keeping track of when markets, fairs, and especially religious ceremonies and festivals were planned helped to create a sense of community and shared understanding of time.

Nevertheless, it is frequently uncertain which type of calendar was employed and whether the presented information is to be regarded as reliable. It is notable that historical dates which have survived were often documented decades or even centuries after the event in question took place. It is similarly conceivable that such sources may have been corrupted, invented, or otherwise altered or added subsequent to the event in question in order to align with a specific narrative.

Moving back in time, the accuracy of dates inevitably declines. The absence of sound chronological standards in the past, makes it basically guesswork. The ancients lack of contemporary recording methods and understanding of historical time further complicate the matter. In small villages there was no need to know the exact time and dates. However, as small villages grew into towns, civilization slowly appeared in the Nile valley. People has noted that certain stars appeared at specific places in the sky year after year, so astronomy became of great importance, as it enabled keeping track of time over longer periods. Nevertheless, dating historical events is challenging, as there was no single system for numbering years in the ancient world. The best we can do is to attempt to create a timeline of events from historical records, inscriptions, and archaeological finds.

The Egyptian calendar

Strangely enough, whether the Egyptian day began at dawn or at sunrise is controversial. The difference affects the Egyptian date assigned to a Heliacal rising of Sothis, and hence the conversion of that date to a Julian year.

The Egyptian civil year consisted of 12 months each with 30 days. To this five extra days were added, making a year 365 days. This was divided into three "seasons" each consisting of four months: Akhet (Inundation or Flood), Peret (Emergence or Growth) and Shomu (Harvest or Low Water). However, a solar year is 365.2425 days, which is why we add an extra day every four years. The ancient Egyptians did not do this, so their calendar lost a quarter of a day every year. After a century this would amount to the same date occuring 25 days earlier, which would completely ruin the seasons, a fact well known to the ancients. They probably corrected the calendar informally so that the seasons didn't move too far out of sync with the sun, perhaps at a particular festival. The Islamic calendar is still lunar, which means that a year is only 354.367 days. This cause its dates to shift almost 11 days each year, making seasons shift from year-to-year.

Dates were usually expressed by the regnal year of a pharaoh, followed by the month, followed by the day, like so: reign of Ramesses II, year 38, III Akhet, day 19. For much of Egyptian history, the months were not referred to by individual names, but were numbered within the three seasons. By the Middle Kingdom, however, each month had its own name that were probably used in daily speech.

| # | Season | Month name | Coptic | Greek |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I Akhet | The one of Thōth | Tôut | Thōth |

| 2 | II Akhet | The one of the Opet feast | Baôba | Phaōphí |

| 3 | III Akhet | [The one of] Hathor | Hatûr | Athúr |

| 4 | IV Akhet | The joining of kas | Koiak | Khoiák |

| 5 | I Peret | The offering | Tôbi | Tubí |

| 6 | II Peret | [The one of] the basket? | Meshir | Mekhír |

| 7 | III Peret | The one of Amenhotep | Baramhat | Phamenoth |

| 8 | IV Peret | The one of Renenutet | Barmoda | Pharmouthí |

| 9 | I Shomu | The one of Khonsu | Bashons | Pakhōn |

| 10 | II Shomu | The one of the Valley | Baôni | Pauni |

| 11 | III Shomu | Uncertain meaning | Apip | Epiphi |

| 12 | IV Shomu | The birth of Ra | Masôri | Mesore |

| Day | Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Birthday of Osiris | |

| 2 | The Birthday of Horus | |

| 3 | The Birthday of Set | |

| 4 | The Birthday of Isis | |

| 5 | The Birthday of Nephthys |

To adjust their calendar they used the Sothic cycle as a long-term framework to keep it aligned with the seasons. This cycle was based on the rising of the star Sirius (Greek:

Chronology in the ancient world

The concept of chronology in the ancient world is not as straightforward as it is today, due to the presence of several inherent complications. In order to establish a chronology, a number of different techniques must be employed.

Regnal years

Administrative documents, production dates, and inscriptions were dated by the regnal year: Reign of King Usermaatra, Year 38, III Akhet, day 20. Regnal years were counted from the day of accession of the king, thus not the same as a civil year. Many ancient cultures used regnal year dating because it provided the most immediate and important dates needed. It was not necessary to know when a particular ancestor ruled, especially legendary ones from centuries ago. When one pharaoh succeeded another, the civil year would change in the middle of the year, overlapping the last year of the previous king with the first year of the new ruler, which meant that Year 1 could range from a few days to almost a whole year.

Synchronisms

Ancient cultures used a wide variety of calendars, the simplest and most common being the lunar calendar. Because each culture had its own system, it is very difficult to convert and synchronise dates between two or more calendars, especially as the accuracy of the records was of varying quality – where such records exist at all. An example of a synchronism, diplomatic correspondence between kings, was unearthed in the ruins of Akhetaten, buried when the ephemeral capital was razed and abandoned. The correspondence provides the names of the kings of two kingdoms and establishes a chronological starting point, thereby allowing the texts to be synchronised to a specific time.

King lists

Documented sequences of kings are very rare, and dated chronological lists even more so, as chronology in the modern sense was unheard of in the ancient world. One of the earliest known lists is Ptolemy's Canon of Kings, a chronological list of the Kings of Mesopotamia, collected in the 3rd century BC from older sources. The foundation of Egyptian chronology is provided by the very fragmentary Turin King List, a papyrus roll from the 12th century BC detailing the order and duration of the reigns of more than 200 Egyptian pharaohs.

Temple and tomb inscriptions frequently include the date of the ruling pharaoh when it was made. However, but this only indicate a minimum

duration of that reign. For instance, the Battle of Kadesh inscription begin with: “Year 5, third month of the harvest season, day 9, under the Majesty of Ramesses II ...”

Furthermore, labelled goods (wine jars etc.) often included the date of production in a similar manner.

Genealogies

Tombs of highly ranked officials often included a record of their ancestry and under which king they served. Furthermore, administrative documents allows scholars to map out families that can verify or act as controls for disputed or lesser known reigns.

Archaeological records

Archaeology provides an invaluable archive of human history, offering tangible evidence that links objects, structures, and other cultural materials to specific time periods and civilisations. The application of scientific techniques, such as radiocarbon dating, enhances the accuracy of these records by establishing more precise timelines, thus enabling archaeologists to situate discoveries within a broader historical context. It is important to note that archaeology only provides the physical evidence, while scientific methods and historical context offer the precise dating.

Astronomical records

Astronomical records were a crucial step in planning and preparing for important future events, including festivals dedicated to the gods, and played an important role in agriculture, helping to predict the seasons, plan planting and harvesting crops, and thus ensuring survival. Modern techniques have made it possible to accurately date descriptions of ancient astronomical events.

Ptolemy's Canon of Kings

Ptolemy of Alexandria, who flourished under Roman rule in the second

century AD, compiled a list of kings, noting the length of their reigns. It is likely that this list was based on even older lists. This

important list ancient kings was used by astronomers as a practical manner of dating astronomical events. Known as Ptolemy’s Canon, it has been preserved by multiple succeeding authors, who often supplemented it with up-to-date knowledge

from their own times. Historians generally regard the Canon to be accurate, and it forms the foundation of ancient chronology from 747 BC forward,

to which all other datings are synchronised.

The Canon is divided into four sections:

20 Babylonian Kings were followed by 10 Persian Kings (538–332 BC) that conquered Mesopotamia. The list was continued by

astronomers in Alexandria, detailing first the Macedonian Kings (331–305 BC), followed by the 10 Ptolemies of Egypt (304–30 BC).

| Name (in Greek) | Transliteration | Reign | Total | Year (BC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babylonian Kings | ||||

| Ναβονασσάρου | Nabonassaros | 14 | 14 | 747–734 |

| Ναδίου | Nadios | 2 | 16 | 733–732 |

| Χινζηρος και Πώρου | Khinzer and Poros | 5 | 21 | 731–727 |

| Ιλουλαίου | Iloulaios | 5 | 26 | 726–722 |

| Μαρδοκεμπάδου | Mardokempados | 12 | 38 | 721–710 |

| Αρκεανου | Sargon II (Arkeanos) | 6 | 43 | 709–704 |

| άβασίλευτα | Without a king | 2 | 45 | 704–703 |

| Βιλίβου | Bilibos | 3 | 48 | 702–700 |

| Απαραναδίου | Aparanadios | 6 | 54 | 699–694 |

| Ρηγεβήλου | Rhegebelos | 1 | 55 | 693 |

| Μεσησιμορδάκου | Mesesimordakos | 4 | 59 | 692–689 |

| άβασίλευτα | Without a king | 8 | 67 | 688–681 |

| Aσαραδινού | Esarhaddon (Asaradinos) | 13 | 80 | 680–668 |

| Σαοσδουχίνου | Saosdouchinos | 20 | 100 | 667–648 |

| Κινηλαδάνου | Kineladanos | 22 | 122 | 647–626 |

| Ναβοττολασσάρου | Nabopolassaros | 21 | 143 | 625–605 |

| Ναβοκολασσάρου | Nabokolassaros (Nebuchadnezzar II) | 43 | 186 | 604–562 |

| Iλλοαρουδάμου | Illoaroudamos | 2 | 188 | 561–560 |

| Νηριγασολασσάρου | Nerigasolassaros | 4 | 192 | 559–556 |

| Ναβοναδίου | Nabonadios | 17 | 209 | 555–539 |

| Persian Kings | ||||

| Κυρου | Kyros (Cyrus the Great) | 9 | 218 | 538–530 |

| Καμβύσου | Kambysos (Cambyses II) | 8 | 226 | 529–522 |

| Δαρείου πρώτου | Dareios the First (Darius the Great) | 36 | 262 | 521–486 |

| Ξερζου | Xerxes (Xerxes I) | 21 | 283 | 485–465 |

| Aρταζερξου πρώτου | Artaxerxes I | 41 | 324 | 464–424 |

| Δαρείου δευτέρου | Dareios (Darius II) | 19 | 343 | 423–405 |

| Αρταξερξου δευτέρου | Artaxerxes II | 46 | 389 | 404–359 |

| Ωχου | Ochos (Artaxerxes III) | 21 | 410 | 358–338 |

| Αρωγού | Arogos (Artaxerxes IV) | 2 | 412 | 337–336 |

| Δαρείου τρίτου | Dareios the Third (Darius III) | 4 | 416 | 335–332 |

| Αλεξάνδρου Μακεδόνος | Alexander the Great | 8 | 424 | 331–324 |

| Macedonian Kings | ||||

| Φιλίππου | Philippos (Philip III Arridaeus) | 7 | 7 | 323–317 |

| Αλεξάνδρου ετερου | The other Alexandros (Alexander IV) | 12 | 19 | 316–305 |

| Πτολεμαίου Λάγου | Ptolemaios Lagos (Ptolemy I Soter) | 20 | 39 | 304–285 |

| Φιλαδελφου | Ptolemy II Philadelphus | 38 | 77 | 284–247 |

| Ευεργέτου | Ptolemy III Euergetes | 25 | 102 | 246–222 |

| Φιλοπάτορος | Ptolemy IV Philopator | 17 | 119 | 221–205 |

| Επιφανούς | Ptolemy V Epiphanes | 24 | 143 | 204–181 |

| Φιλομητορος | Ptolemy VI Philometor | 35 | 178 | 180–146 |

| Ευεργέτου δευτέρου | Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II | 29 | 207 | 145–117 |

| Σωτηρος | Ptolemy IX Soter | 36 | 243 | 116–81 |

| Διονύσου νέου | Ptolemy XII Auletes Dionysos Neos | 29 | 272 | 80–52 |

| Κλεοπάτρας | Kleopatra (Cleopatra VII) | 22 | 294 | 51–30 |

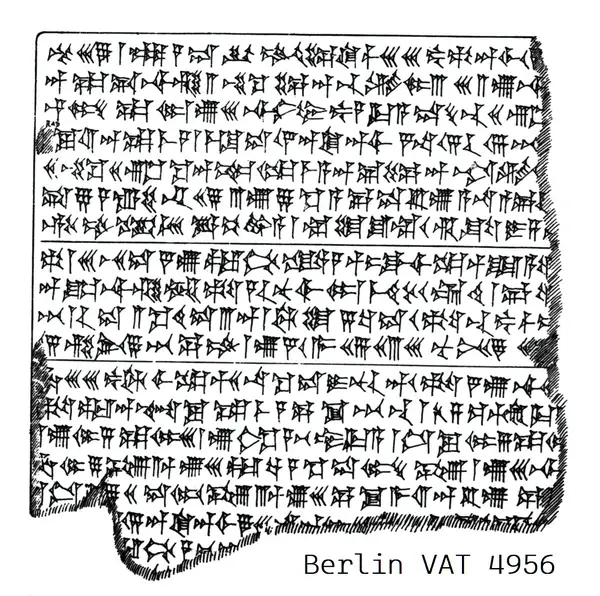

The Astronomical Tablet of Nebuchadnezzar II is a cuneiform tablet that details a series of astronomical observations during the 37th year of the Babylonian king's reign. Modern astronomy shows that the only year that matches the dates within centuries is 567 BC. This would mean that the first year of Nebuchadnezzar's reign was 604 BC, which is perfectly consistent with the canon. There are several biblical references to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II that provide a link with Hebrew chronology, which together with other contemporary king lists further confirm the validity of Ptolemy's sequence of kings, providing reasonably accurate dates as going back to 747 BC.

The Julian calendar

When administering the rapidly expanding Roman Empire, it became clear that a calendar was needed to coordinate the many local calendars in use. This calendar would be used throughout the Empire. The Romans recognised the Julian calendar's greater accuracy compared to the old Egyptian calendar and adopted it as their primary calendar, which later became the standard for most of the Western world. The Julian calendar added an extra day every four years.

Like the Egyptians, the Romans did not number each year sequentially from a specific year, but instead differentated years by naming the two elected consuls in Rome serving a specific year. For example: in the Year of Braccus and Cassius, the Consuls were Cassius and Braccus, and if Cassius served multiple times, the second time his name would have an additional number, Braccus and Cassius II, the third time, Probus and Cassius III, and so on.

The lists of the elected consuls, the Fasti consulares, were originally engraved on marble tablets erected in the Roman forum, and survive in the writings of several historical accounts, along with fragments from various places throughout the Empire.

In the middle of the first century BC, the Roman scholar Terentius Varro established a system that place the traditional foundation of Rome as year 1 ab urbe condita (A.U.C.). The year of the founding of the Republic was available from the fasti, and Varro simply added seven generations before that, counting each generation as 35 years (7 × 35 = 245). From Cicero we learn that according to the annals of the Greeks, Rome was founded in the second year of the seventh Olympiad.

Eratosthenes of Cyrene established the use of the Olympiad and the individually numbered years between them in the third century BC. Olympic dates survive in Eusebius' Chronicon, which attempted to reconcile the events of biblical history with classical historical material, and was only used for historical purposes, never for everyday use. The second part of Chronicon, the Canons, puts the historical material into a parallel timeline, listing the reigning rulers of each nation side-by-side, for every year. Jerome's Latin translation, written in Constantinople around 380, preserves the chonological tables. The original is lost, but survives in copies made by later writers.

The Anno Domini (AD) was developed by the monk Dionysius Exiguus in 525 AD (A.U.C. 1278), as a result of his work on calculating the date of Easter, but was not widely used until the 9th century. He produced tables with a 19-year cycle for calculating Easter but also years since the birth of Christ, which is the basis of the AD system:

Nineteen year cycle of Dionysius (Cyclus decemnovennalis Dionysii)

First Argumentum. On the years of Christ. If you want to find out which year it is since the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ, compute fifteen times 34, yielding 510; to these always add the correction 12, yielding 522; also add the indiction of the year you want, say in the consulship of Probus Junior, a 3, yielding 525 years altogether. These are the years since the incarnation of the Lord.

Consulting Dionysius’ Easter table, which includes years in the era of the Roman emperor Diocletian, we see that Probus was consul in the year 241 of Diocletian. Subtracting 241 from 525 gives 284, the year in which Diocletian became emperor.

Although Moses was a first-hand witness to what he wrote, the Bible is not very helpful as it does not name the Pharaohs in the time of Moses and Joseph. However, a few Late Period pharaohs were named: Shishak (1 Kings 11:40), Tirhakah (2 Kings 19:9), Hophra (Jeremiah 44.30), and Neco (2 Kings 23:29).

Syncronizing events and calendars

So, with that out of the way, how do we go about to establish a chronological link between today and a pharaoh? We could simply look it up in a book on the subject, but that does not actually teach us anything. Instead, we will trace the path and then actually walk that path. It's important to acknowledge the role of Roman influence in the study of ancient chronology, as most surviving texts have passed through a Roman "filter", influencing the development of our understanding of ancient history.

Chronology

- 2025

The current year.

- 1582

The Gregorian calendar adopted. All dates before this use the Julian calendar.

- 643

Arabic-Greek Papyrus PERF 558 is dated by Islamic (1 Jumada al-Thani 22 AH) and Coptic (30 Baramudah I, 360 AM) dates, corresponding to 25 April 643.

- 525

Dionysius developed Anno Domini in 525 = A.U.C. 1278 = 241 Anno Martyrum.

- 284

The Alexandrian calendar used by the Coptic church start in 284 AD, and is year 1 Anno Martyrum – the year Diocletian became Roman Emperor.

- 27 BC

Octavian becomes Augustus, the first Roman emperor.

- 30 BC

The last pharaoh of Egypt, Cleopatra, is defeated by Octavian and commits suicide.

- 509 BC

Rome becomes a republic = A.U.C. 245.

- 747 BC

The first Babylonian king Nabonassaros of Ptolemy's Canon of Kings started his reign 696 years before Cleopatra started hers.

- 753 BC

The traditional foundation of Rome = A.U.C. 1.

- 763 BC

June 15 solar eclipse in Sicily is used to fix the chronology of the Ancient Near East. (Diod. 20.5.5)

- 776 BC

First Olympiad.

Chronology becomes increasingly unreliable the further back in time you go, as records become scarce or sketchy. This is not to say that it is impossible – historians are some very clever people and they have managed to find very elusive evidence to form a coherent and working chronology for very ancient times. However, it is not always possible or necessary to establish exact dates.

Cleopatra, the last of the Pharaohs

We know from Plutarch that during Octavian's fifth consulship, which he shared with Antony, Octavian defeated Cleopatra and Antony in Egypt. This was before he was given the title Augustus, which is clear as he was still known simply as (Imperator) Caesar.

The Fasti Capitolini have a gap for the years around the fifth consulship, but the The Chronograph of 354 records it in AUC 725, but with Appuleius, as do the Fasti of Hydatius, but with Pulchro (alt. Appuleius). This is typical of antiquity - conflicting and/or incomplete information.

The Chronicon Paschale tells us that Augustus (Octavian) landed in Egypt AUC 727 (Anno Mundi 5477) and halted the reign of the Ptolemies, which had lasted 296 years, which according to Ptolemy's Canon of Kings lasted 294 years.

As we have learned above, AUC 1278 = 525 AD. There are 553 years between AUC 725 and AUC 1278. Subtracting 525 AD from those 553 years yield -28. Since there was no year zero, we have to increase it by one, and thus we arrive at -29 = 29 BC ≈ 30 BC, the date commonly used by historians.

All Roman dates, if they are complete and reliable, can be directly expressed in Julian years. All the other datings of ancient chronology are linked to our reckoning by direct or indirect synchronisms with Roman dates.

References

1

Ptolemy's Canon at livius.org.3

List of preserved consuls in the mid-16th century manuscript Codex Vindobonensis 3416 in Vienna, aka. The Chronography of 354.4

Cornell, Tim. J., 1995. The beginnings of Rome. London: Routledge. p. 73.5

Cicero, The Republic, 2.186

Plutarch, Life of Antony 11 & 30.