Gustav Seyffarth’s hand drawn copies, tracings, squeezes and rubbings of hieroglyphics and sketches can be found in volume VII of the unpublished Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca Manuscripta, held by the Brooklyn Museum. This volume contain some 1500+ pages from his time in Turin (Volume VII, MSS 6283-7828). Gardiner enumerated the relevant pages, but since this volume is not published, it is here purely for the sake of completness:

S11 – No. 6804-6830

S12 – No. 6831-6856

S13 – No. 6857-6935

S2 – Pasting of the 164 fragments by Seyffarth,

as seen by Lepsius and Wilkinson.

S3 – No. 6413.

The numbering scheme of the 164 numbered fragments of the Turin King List derives from Carl Richard Lepsius’ Auswahl in 1842. Giulio Farina added a few fragments in his 1938 edition when remounting the papyrus, as noted by Gardiner in The Royal Canon of Turin from 1959. Gardiner examined the papyrus in great detail, complete with a concordance of the fragments, but the details lacked in depth. As of 2022, a new editon of the king list is in the works, the first preliminary results indicate the addition of a few new fragments, as well as new positions found for some of the original fragments. It should be noted that while Lepsius’ preserve the original papyrus, there are several minor discrepancies. Some hieratic signs are actually missing in the photos, especially at the edges of the fragments. There are also a few minor discrepancies between the editions of Lepsius and Wilkinson.

2023: A new position of fr. 2 has been found, which is confirmed by the writing on the recto and verso, plus the fibres match perfectly. The new position is at the end of 3.8, adding the text:

2023: A possible new position of fr. 4 has been found by shifting Seyffarths placement at 3.10-11 up one row to 3.9-10, which seems to be confirmed by the writing and matching fibres. The red signs are clearly a heading or summation, and the bracket surrounding the row below shows that the end of the previous column is encroaching on the column.

Outdated: Ryholt's suggestion to place fr. 40 to the left of fr. 43 is impossible since the writing on the recto does not align, nor does the fibres match. Furthermore, the suggested solution by Malek to place it to the left of fr. 108 seem possible because there seems to be a fibre correspondence, although most of the fragment does seem to consist of a patch.

Special considerations

fr. 59 Seyffarth had joined a fragment with a large top margin

at the top right side of fr. 59 but it was moved to the left of fr.

59 by Farina, despite there being a clear horizontal fibre match.

Gardiner left the fragment where Farina placed it, but remarked that

the position was doubtful.

fr. 71 This fragment has no fibre correspondence with the

surrounding fragments and Ryholt suggests it may be disregarded,

while still placing it in col. 7 on his fig. 10. The placement is

clearly to be regarded as uncertain.

(Ryholt 1997: 22)

Fragments added by Farina

The following fragments were added at the Ibscher/Farina remounting in the 1930’s. These fragments are not present in the editions of Lepsius or Wilkinson. Gardiner marked these fragments with question marks, which is imprecise, so they are designated according to the positions he established. The numbering of the fragments is continued from the last fragment (164) of Lepsius. The numbering is not official and only to help with referencing the fragments.

The 2022 reconstruction

The extensive research of Egyptologist Kim Ryholt, has created a new reconstruction of the document while collaborating closely with Egyptologist Rob Demarée, served as the foundation for the restoration. In 2022, one of the foremost experts in papyrus restoration in the world, Myriam Krutzsch from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, worked on the King List for ten weeks in Turin, where she removed all traces of the previous glue and fabrics used to join the fragile parts together by Seyffarth in 1826, and by Ibscher and Farina in the 1930s. The cleaning process showed that many of the numbered fragments were themselves made up of even smaller fragments, revealing just how impressive and good Seyffarth's reconstruction of the fragments was.

After this difficult cleaning process, the fragments fibres of the papyrus was meticulously examined before consolidating them. 10 new fragments were added to the manuscript's structure, and Kim Ryholt has placed several others in light of his recent research. The numbering of the fragments is continued from the last fragment of Farina (176). The numbering is not official and only to help with referencing the fragments.

The columns and their fragments

The fragments ordered by their placement in each of the eleven columns.

- Column 1 1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 51

- Column 2 89, 41, 42, 150, 151, 152, 22, X/24-26

- Column 3 3, 1, 20, 21, 19, (23), 30

- Column 4 18, 136, 31, 32, 17, 33, 34, 38, 45

- Column 5 59, 133, 135, 43, (40), 61, 63, 44, 46, 47, 48, 36

- Column 6 59, V/7, V/8, 61, 62, 84, 85, 63, V/17-18 64, 67

- Column 7 72, VI/13, 81, 73, 74, 75, 77, 70, 76, 78, 71, 79, 80

- Column 8 81, 97, 86, 83, 87, (90), 88, (82), 93, VII/12, 94, 95, VII/20, 134

- Column 9 97, (108), 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 69, 103, 104, 123

- Column 10 105, 108, 112, X/13, X/16-17, X/20-21

- Column 11 125, 126, 127, 130, 131, 142, 163, 164

The papyri sheets

The fragments order on each of the seven papyri sheets. The sheets are numbered from the right to the left of the recto (the original papyrus roll), meaning the numbering of the canon (also from the right to the left) on the verso goes from 7 to 1.

- Sheet 7 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 51, 89, 41, 42, 150, 151, 152, 22, X/24-26

- Sheet 6 (?), 3, 1, 20, 21, 19, (23), 30

- Sheet 5 (23), 30, 18, 136, 31, 32, 17, 33, 34, 38, 45, 133, 135, 43

- Sheet 4 59, 133, 135, 43, (40), 61, 63, 44, 46, 47, 48, 36, 59, 61, 62, 84, 85, 63, 64, 67

- Sheet 3 72, 81, 73, 74, 75, 77, 70, 76, 78, 71, 79, 80, 97, 98, 80, 86, 83, 87, (90), 88, (82), 93, 94, 95, ?, 134

- Sheet 2 97, (108), 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 69, 103, 104, 123, 105, 108, 112, X/13, X/16-17, X/20-21

- Sheet 1 125, 126, 127, 130, 131, 142, 163, 164

The Champollion fragments

Champollion copied the fragments he discovered in 1824 into a

notebook. However, several of these fragments were not part of

Seyffarth’s reconstruction in 1826, and their current whereabouts is

unclear. The fragments were published by Champollion’s brother in

1851, where he also commented on the missing fragments. (... there are also eight fragments missing in the lithographs

of Lepsius. These fragments, still unpublished, give us four

names of kings in sets of two).

These ‘lost’ fragments were marked K, Q, R, Dd, Ii, Mm, Rr and

Ss by Champollion. Contrary to the claim of Champollion’s brother,

most of the lost fragments only show parts of and at most the cartouche open with the almost ubiquitous

| Ch. | Fragment | Ch. | Fragment | Ch. | Fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 81 (8.1-8.5) | Q | — | Gg | 18 (4.4-4.6) |

| B | 97 (9.1-9.6) | Qbis | 93 (8.24-8.27) | Hh | 34 (4.23-4.26) |

| C | 72 (7.7-7.11) | R | — | Ii | 98 (9.11-9.13) |

| D | 72 (7.1-7.2) | S | 126 (11.5-11.8) | Jj | 98 (9.7-9.11) |

| E | 101 (9.23-9.27) | T | 98 (9.12-9.14) | Kk | 61 (5.14, 6.13-14) |

| F | 20 (3.16-3.17) | U | 22 (2.21-2.23) | Ll | 34 (4.17-4.19) |

| G | 76 (7.19-7.21) | V | 126 (11.3-11.5) | Mm | — |

| H | 101 (9.20-9.22) | X | 93 (8.22-8.24) | Nn | 1 (3.7-3.12) |

| I | 108 (8.5-8.10) | Y | 159 (does not belong?) | Oo | 79 (7.23-7.24) |

| J | 76 (7.19-7.21) | Z | 126 (11.3-11.5) | Pp | 79 (7.25-7.27) |

| K | — | Aa | 34 (4.23-4.24) | 34 (4.14-4.16) | |

| L | 31 (4.8-4.9) | Bb | 97 (9.3-9.6) | Rr | — |

| M | 72 (7.12-7.13) | Cc | 108 (copy of I?) | Ss | — |

| N | 101 (9.15-9.19) | Dd | 20 (3.18-3.22) | Tt | 59 (5.3-5.4) |

| O | 79 (7.24-7.27) | Ee | 152 (2.17-2.18) | Uu | 1 rt (recto of Nn) |

| P | 97 (7.3, 8.1-6) | Ff | 18 (2.17-2.18) | Vv | 72 (7.1-7.3) |

| Fr. | Champollion | Fr. | Champollion | Fr. | Champollion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nn [Uu] | 61 | Kk | 97 | B, P, Bb |

| 18 | Ff, Gg | 72 | C, D, M, Vv | 98 | T, Ii, Jj |

| 20 | F, Dd | 76 | G, J | 101 | E, H, N |

| 22 | U | 78 | V | 108 | I, Cc |

| 31 | L | 79 | O, Oo, Pp | 126 | S, Z |

| 34 | Aa, Hh, Ll, Qq | 81 | A | 152 | Ee |

| 59 | Tt | 93 | Qbis, X | 159 | Y (does not belong?) |

Reconstructing the papyrus.

It might seem natural to start by placing the rightmost

fragments, but the obvious place to start is by placing the

largest and most complete fragments and work backwards from

there. When the fragments’ fibres line up vertically (V) and/or

horizontally (H), this is known as “fibre correspondence,”

(marked as

- 1 Place fr. 81 at the top.

- 2 Place fr. 72 to the right of fr. 81 (H

fc ). - 3 Place fr. 73 (V/H

ƒc with fr. 81). - 4 Place fr. 74 (V/H

ƒc with fr. 81 and Vƒc with 72). - 5 Place fr. 83 below fr. 81 (V

ƒc ). - 6 Place fr. 86 below fr. 81 (V

ƒc ). - 7 Place fr. 76 below fr. 72 (V

ƒc ). - 8 Place fr. 77 to the left of fr. 72 and 76 (H

ƒc ). - 9 Place fr. 70 to the left of fr. 77 (H

ƒc ). - 10 Place fr. 87 to the left of fr. 70 (H

ƒc ). - 11 Place fr. VII/20 to the left of fr. 87. (H/V

ƒc ). - 12 Place fr. 78 to the left of fr. 76 (H

ƒc with fr. 76, Vƒc with fr. 77). - 13 Place fr. 80 to the left of fr. 78 (H

ƒc ). - 14 Place fr. 79 to the right of fr. 78 (H

ƒc ). - 15 Place fr. 93 to the left of fr. 80 (H

ƒc ). - 16 Place fr. 94 to the left of fr. 93 (H

ƒc ). - 17 Place fr. 95 to the left of fr. 93 (H

ƒc ) and below fr. 94 (Vƒc ). - 18 Place fr. 82 to the right of fr. 94 (H

ƒc ) and above fr. 93 (Vƒc ). - 19 Place fr. VII/20 at the left top corner of fr.

87 (V/H

ƒc )

Unplaced fragments

There are a number of fragments that cannot be placed with certainty. Evidence is needed to corroborate their correct position, either by fibre corroboration, or consideration of the text on the recto. Some have had their position changed over time, as more thorough examinations of the papyrus were undertaken, but many still remain unplaced because their position can not be determined conclusively.

Giulio Farina, the director of the Turin Museum from 1928, together with papyrus conservation specialist Hugo Ibscher, began restoration of the papyrus in July 1930. Ibscher detached the 164 fragments from the blotting paper on which Seyffarth had glued them, and rearranged the fragments taking careful note of the fibres. Some fragments that did not belong to the papyrus were naturally removed; and some that had previously been impossible to reunite (probably from inv. no. 281), were added as matching fibres were established. The reassembly caused some minor damage along the edges and many minute signs or traces of signs were lost on some fragments, making the facsimiles of Lepsius and Wilkinson all that more important, as they preserve signs that are now lost.

To protect the papyrus, the fragments were placed between two glass panes in three separate frames. Over the next few years, Farina sorted through the unpublished fragments held at the museum, tweaking the positions of the fragments, until he was satisfied with the final arrangement in October of 1934.

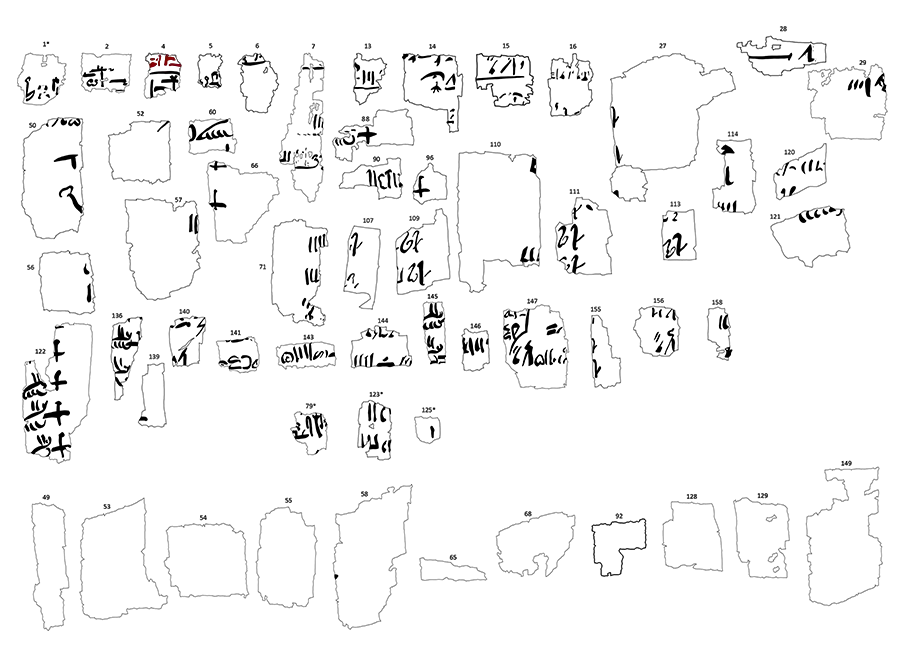

Gardiner’s examination discarded 25 fragments as belonging to other papyri, while 15 fragments were classified as useless or doubtful, and another twelve as completely blank; they were not commented on further, and supposedly belong to the papyrus. Five fragments only contain traces, while another five only hold the sign for year, or part of the king’s title. In all, Gardiner retained 102 numbered fragments[*] on his plates, plus ten unnumbered fragments marked by question marks, added to Seyffarth’s original sheets by Ibscher or Farina.[*] These ten unnumbered fragments are referenced by Gardiner’s position.

The museum have an unknown number of unpublished fragments with

parts of royal names of both kings and gods, figures relating to the

reigns, and parts of headings and summations.

Determining possible positions for the unplaced

fragments require an exhaustive examination looking for any fibre

correspondence with the already placed fragments. Until a full

investigation of the fragments can be undertaken, progress is only

possible in small increments.

| Remark | Fragments |

|---|---|

| Unplaced (17) | 1, 2, 4, 7, 29, 40, 36, 48, 50, 75, 90, 133, 135, 141, 145, 147, 30a |

| Does not belong (25) | 24, 25, 26, 35, 37, 39, 91, 106, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 124, 132, 137, 138, 148, 153, 154, 157, 159, 160, 161, 162 |

| Doubtful/useless (15) | 5, 6, 13, 14, 15, 16, 27, 28, 107, 120, 121, 134, 140, 144, 146, 158 |

| Blank on vs (12) | 49, 51, 53, 54, 55, 58, 65, 68, 92, 128, 129, 149 |

| Traces (5) | 52, 56, 57, 114, 139 |

| Years/title (5) | 109, 111, 113, 136, 155, 156 |

Unpublished fragments

The archives at the Museo Egizio in Turin hold an unspecified number of unpublished fragments collected in four frames. These frames are referred to as Cat. 1874/2, 1874/3, 1874/4, and 1874/5. Despite many examinations by Egyptologists, they remain unplaced, as their positions cannot be determined as there is apparently no clear fibre or text correspondence with the placed fragments of the papyrus. Most of these fragments are expected to be quite small, only holding parts of royal names, figures, and headings and summations.

In 2022, a new reconstruction was finally performed, that is, a thorough examination with modern tools and expertise. This ensured that all possible fragments showing any correspondence were added to the new reconstruction. Further details may be revealed upon publication of the results in 2024, which is also the bicentenary of the discovery of the papyrus.

In early 2024 photos of both sides of four panels with fragments were made available on Turin Papyrus Online Platform at the Museo Egizio website. This means that we finally have access to all the fragments. Finally! It only took 200 years... :)

- C. 1874 vetro 1 + 4: 23 (24) fragments

- C. 1874 vetro 2: 36 (37) fragments

- C. 1874 vetro 3: 31 fragments

- C. 1874 estratto 2022: 12 fragments removed 2022

All in all, the four panels hold 101 (103) fragments, many very tiny. Some of the fragments can be seen in the plates of Lepsius, but there are a number of new ones.

Bibliography

- Allen, James P. 1999. ‘The Turin Kinglist’. BASOR 315: 48–53.

- ———. 2010. ‘The Second Intermediate Period in the Turin king-list’, in M. Marée (ed.), The Second Intermediate Period (Thirteenth - Seventeenth Dynasties): Current Research, Future Prospects, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 192: 1–10.

- Barta, Winfried. 1983. ‘Bemerkungen Zur Rekonstruktion Der Vorlage Des Turiner Königspapyrus’. GM 64: 11–13.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von. 1962. ‘The Date of the End of the Old Kingdom of Egypt’. JNES 21: 140–47.

- ———. 1964. Untersuchungen zur politischen Geschichte der Zweiten Zwischenzeit in Ägypten. Glückstadt: Augustin.

- ———. 1966. ‘Die Dynastie der Herakleopoliten (9./10. Dynastie)’. ZÄS 93: 13–20.

- ———. 1976. ‘Die Chronologie der XII. Dynastie und das Problem der Behandlung gleichzeitiger Regierungen in der agyptischen Überlieferung’. SAK 4: 45–57.

- ———. 1984a. ‘Bemerkungen zum Turiner Königspapyrus und zu den Dynastien der ägyptischen Geschichte’. SAK 11: 49–58.

- ———. 1984b. Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. MÄS 20. München: Deutscher Kunstverlag.

- ———. 1995. ‘Some Remarks on Helck’s “Anmerkungen zum Turiner Königspapyrus”’. JEA 81: 225–27.

- ———. 1999a. ‘Anmerkung zu zwei unbeachteten Fragmenten des Turiner Königspapyrus’. GM 168: 19–21.

- ———. 1999b. Handbuch der Ägyptischen Königsnamen. 2nd ed. MÄS 49. Mainz: P. von Zabern. Birch, Samuel. 1843. ‘Observations upon the Hieratical Canon of Egyptian Kings at Turin.’ TRSL 2, 1: 203–8.

- Brugsch, Heinrich. 1859. Histoire d’Égypte des les premiers temps de son existence jusqu’à nos jours. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

- Champollion, Jean-François. n.d. Papiers de J.-Fr. Champollion Le Jeune. XVI Canon Hiératique des dynasties Égyptiennes. NAF 20318. Vol. 16. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Champollion-Figeac, Jacques Joseph. 1851. ‘De la table manuelle des Rois et des dynasties d’Égypte ou papyrus royal de Turin, de ses fragments originaux, de ses copies manuscrits ou Imprimées, et de ses intreprétations’. Revue Archéologique 7 (2): 397–402, 461–72, 589–99, 653–65. Plate 149.

- Farina, Giulio. 1938. Il Papiro dei re, restaurato. Rome: G. Bardi.

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson. 1959. The Royal Canon of Turin. Oxford: Griffith Institute.

- Goedicke, Hans. 1956. ‘King ḤwḏfꜢ?’ JEA 42: 50–53.

- Helck, Wolfgang. 1956. ‘Untersuchungen zu Manetho und den ägyptischen Königslisten’. UGAA 18. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- ———. 1992. ‘Anmerkungen zum Turiner Königspapyrus’. SAK 19: 151–216.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1979. ‘P. Turin N.1874, Vso.’ In Ramesside Inscriptions 2:827–44. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lauth, Franz J. 1865. Manetho und der Turiner Königspapyrus. Munich: Wolf.

- Lepsius, Karl Richard. 1842. Auswahl der Wichtigsten Urkunden des aegyptischen Alterthums. Leipzig: Wigand.

- Málek, Jaromír. 1982. ‘The Original Version of the Royal Canon of Turin’. JEA 68: 93–106.

- Meyer, Eduard. 1904. Aegyptische Chronologie. Berlin: Verl. der Königl. Akad. der Wiss.

- Möller, Georg. 1927. Hieratische Paläographie. Die aegyptische Buchschrift in ihrer Entwicklung von der fünften Dynastie bis zur römischen Kaiserzeit. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Osnabruck: Otto Zeller.

- Ryholt, Kim. 1997. The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c. 1800-1550 B.C. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- ———. 2000. ‘The Late Old Kingdom in the Turin King-List and the Identity of Nitocris’. ZÄS 127: 87–100.

- ———. 2004. ‘The Turin King-List’. Ägypten Und Levant 14: 135–55.

- ———. 2008. ‘King Seneferka in the king-lists and his position in the early dynastic period’. JEH 1: 159–73.

- ———. 2018. ‘Seals and History of the 14th and 15th Dynasties’. In The Hyksos ruler Khyan and the early second intermediate period in Egypt : problems and priorities of current research, ErghÖJh 17: 235–76.

- Wilkinson, John Gardner. 1851. The Fragments of the Hieratic Papyrus at Turin. 2 vols. London: Richards.