Scenes copied from sites in ancient Egypt were painted specfically on the walls and roofs of the Neues Museum in Berlin. These were destroyed during the Second World War, which left the Museum in ruins.

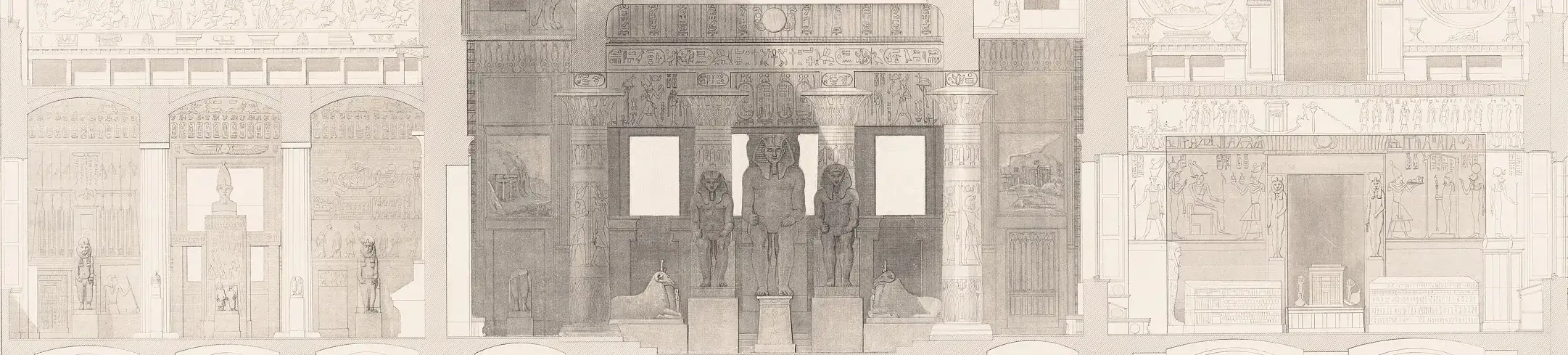

The Neues Museum (New Museum) is a museum in the historic centre of Berlin, Germany. Built between 1843 and 1855 by order of King Frederick William IV of Prussia in neoclassical and renaissance styles, it was officially opened in 1859, and is considered as the major work of architect Friedrich August Stüler. It is unclear whether the all the murals were completed, as the photo of the Historical Hall from 1920 (see below) seems to have blank walls, apart from the cartouches of the kings.

During the Second World War, the museum was badly damaged by Allied bombing and several sections were completely destroyed. The collections had been moved and secured as early as 1939, and after the war they were redistributed among the various museums in the city, but the murals were left in place, obviosly. The building itself was left in ruins, abandoned to the elements by the East German authorities until it was finally decided to rebuild it in 1985. After the collapse of the Berlin Wall, what was left was restored from 1999 to 2009 by architect David Chipperfield.

Immediately to the right of the museum entrance is the Egyptian section. The rooms are now very different as the original scenes were

destroyed in the war. The new museum

had a number of rooms with murals (painted walls) depicting actual scenes from tombs and monuments

in Egypt. The museum was created as a walk-through of cultures from the Stone Age right up to the Modern Era, making it an unique experience. The

central room was designed as a columned courtyard with vividly painted walls and roofs. The Mythological Hall had murals with processions of gods,

while the Historical Hall had scenes of pharaohs from earliest times through Egypt's long history to the last pharaohs and even Roman emperors.

Above the murals there was a frieze with 376 cartouches in a consequtive list of names of kings and queens, from Menes to emperor Decius, followed

by a number of Ethiopian names. The rooms were filled with treasures such as sarcophagi, statues, scarabs, papyri, jewellery and many other objects

from ancient Egypt.

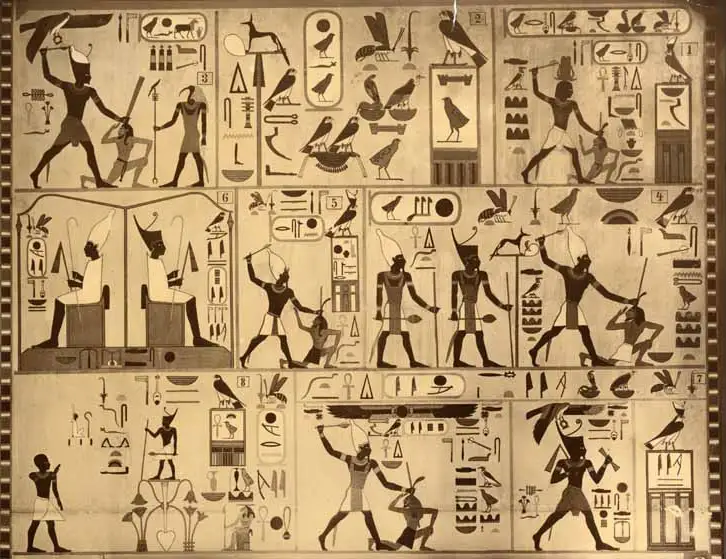

The Egyptian rooms of the museum were painted by members of the Lepsius expedition to Egypt in 1842–46. The murals were painted for the Neues Museum by the brothers Max and Ernst Weidenbach under the supervision of Georg Erbkam; the two of them designed all the Egyptian representations in a size suitable for the walls, and the reproduction of these murals by lithographic engraving owes its stylistic fidelity to Ernst. The huge number of rubbings, paintings and line drawings brought back from Egypt meant that there was no shortage of scenes to choose from. The murals in the various rooms were published in detail by Lepsius in 1855.

English translation of the 1855 book.

The original names are kept as written, i.e., Amuntuankh is not corrected to Tutankhamun. Only the Greek letter Chi, χ, has been transcribed as kh.

Carl Richard Lepsius. 1855. Königliche museen. Abtheilung der Ägyptischen Alterthümer. Die Wandgemälde der verschiedenen Räume. (Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung). 21 pp., 37 pls.

Royal Museums. Department of Egyptian Antiquities. The wall paintings of the different rooms. 37 plates with explanations.

In arranging the rooms of the Egyptian Museum, the aim was to create not only a spatial, but also a historical and art-historical background, through which the individual disparate monuments of this distant cultural epoch could be more easily understood and brought to life for the viewer. An overview of the history, mythology and private life of the ancient Egyptians presented to the eye in wall paintings was intended to introduce the viewer to the factual circle of Egyptian ideas from which their monuments had emerged, and the restriction to copies of existing ancient Egyptian depictions made it possible, by means of the most faithful reproductions of the Egyptian style and forms in larger dimensions and a richer selection than any collection of originals can offer, to place the visitor immediately on the ground of the Egyptian view of art, from the context of which the individual must be judged.

The establishment of the museum coincided with the return of the scientific expedition that had been sent to Egypt by His Majesty the King in the years 1842-1846. This not only ensured that the premises could be calculated from the outset to accommodate the full extent of the monuments already present and those to be added, but also prompted the museum to be decorated from the same historical point of view that had been the guiding principle during that expedition and therefore also in the creation of its collections. The technical execution, however, benefited considerably from the involvement of the members of the expedition who were familiar with the Egyptian style through long practice, namely the building inspector G. Erbkam, and the brothers Max and Ernst Weidenbach; the latter two designed all the Egyptian depictions in the size suitable for the walls, and the present reproduction of these murals by lithographic engraving owes its successful and stylistically faithful conception to the older of them.

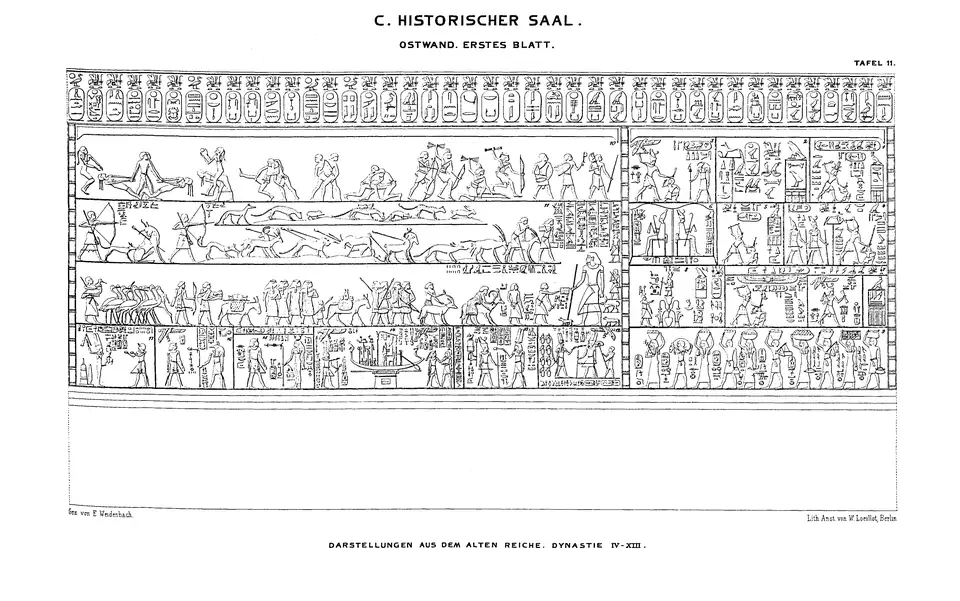

C. Historical Hall (plates 11-20)

The preferably historical monuments, by which we mean those whose epoch can be determined more precisely, especially by depicting or mentioning kings, have been placed in the Hall of Tombs (d), as far as they belong to the Old Kingdom, and those of the New Kingdom and later periods in the Long Hall (C). As the walls of the burial hall were not suitable for depictions, the historical murals the historical murals of both the Old and New of the New Kingdom the latter hall. have been united in the latter hall.

A selection of characteristic depictions from all periods that have left us their legacy fills the four sides of the room in chronological order. They begin next to the front southern entrance. From here, the long main wall is taken up by pictures from the Old and the heyday of the New Kingdom up to the twentieth dynasty. This is followed by the narrow wall behind the pillar and half of the long window wall for the rest of the New Kingdom; then come the Greek and Roman periods, which are followed by several Ethiopian depictions in the last window and on the narrow wall behind the canopy. The series of royal cartouches from Menes through the Hyksos period and the New Kingdom to the Ptolemies and Roman emperors forms a frieze that closes off the wall at the top and extends almost completely to the Emperor Decius in the middle of the third century AD. The cartouches of the Aethiopian kings of Meroe are again added on the last narrow page.

Plate 11

East wall. First sheet.

The frieze contains the cartouches from Menes to the Eleventh Dynasty. Until the Sixth Dynasty, each king had only one cartouche; King Pepi in the Sixth Dynasty initially had two, the second of which always contained the title ‘Son of the Sun’.

The depictions on this sheet cover the Old Kingdom to the Thirteenth Dynasty, under which the Hyksos victoriously invaded the country. The oldest monuments date from the time of the Great Pyramids of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty. However, the Great Pyramids of Dahshur and the depictions of King Snofru, the presumed builder of one of these two pyramids, most likely date to the end of the Third Dynasty. Depictions from the oldest dynasties only survive in private tombs. The earliest images of kings are found in rock inscriptions in the Sinai Peninsula, where the pharaohs had established Egyptian colonies to exploit copper mines.

- Third Dynasty: King Snofru seizes an enemy by the scruff of the neck to kill him. (Wadi Maghara)

- Fourth Dynasty. Names of King Khufu (Cheops), the builder of the largest pyramid. (W. Maghara)

- King Khnum-Khufu kills an enemy. Before him stands the ibis-headed Thoth (Hermes). (W. Maghara)

- Fifth Dynasty King ...ura slays an enemy. Behind him the king follows twice more, first with the double royal crown, then with the upper crown alone. (W. Maghara)

- King Sesurenra kills an enemy. (W. Maghara)

- Sixth Dynasty King Pepi (Phiops, Apappus) enthroned on the right with the lower royal cap, clad on the left with the upper one, as a sign of what appears to be his united rule over Upper and Lower Egypt. (Hamamat)

- The same king with lower pschent engaged in a symbolic action; behind him killing an enemy with the upper pschent. (W. Maghara)

- King Merenra, standing on a symbol of Egypt, worshipped by a man. (Aswan)

- A procession of villages, symbolised by men and women bringing the fruits of the land to their lord. In front of them are the names of the villages, which are often combined with the name of the reigning or a former king.

- Twelfth Dynasty. War and wrestling games; finally jugglers, men and women producing gymnastic arts and other skills. (Benihassan)

- At the top, a hunt for wild animals, gazelles, lions, panthers, hares, etc. Fantastically shaped animals are also mixed in. Below them on the right is a governor of the king, Nehera, son of Khnumhotep, behind him a servant and several dogs. A royal scribe, Nofrhotep, hands him a document dated to the sixth year of King Sesurtesen II. It concerns the introduction of a number (37 according to the inscription) of foreigners with their wives and children. The leader, called Absa, leads the way, bringing a billy goat as a gift, as does the man behind him. The men carry bows and spears; the donkeys are loaded with children and war equipment; the women walk in the middle; the men behind also carry a lyre similar to the Greek one. The flock of large waterfowl driven by an Egyptian has no direct connection with this. Champollion (Lettres, p. 76) thought that the strangers were captive Ionian Greeks because of the clothing, the physiognomies, the lyre and the fluted columns, which he called protodoric, in the tombs of Benihassan from which the representation was taken. He misjudged the period of these images, attributing them to the Twenty-third Dynasty instead of the Twelfth. Wilkinson (Mod. Eg. Vol. II. p. 50) was inclined to see the immigration of Jacob with his family here, which he considers to be simultaneous with this Sesurtesen. Brugsch sees the envoy of a subjugated tribe bringing a tribute of eye make-up to the king (Reiseberichte p. 98). But prisoners and tribute bearers do not come with weapons and music, with wife and child. It is a family seeking protection and welcome, bringing with them gifts from their armies; an entry that immediately recalls that of Jacob, but could not be Jacob himself, because it took place centuries before Jacob's time, not to mention other things. At the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, the Hyksos, a Semitic people, invaded from Asia. The immigrants are called Aamu, and therefore belonged to the neighbouring peoples to the north-east, whose peaceful immigration may have preceded the hostile invasions for centuries. These peaceful forerunners are probably the 37 Aamu, whose arrival is depicted here.

- King Sesurtesen I appears before the sparrow-headed sun god sun god Montu, who brings him a number of captured Aethiopes to him. (Stele in Florence from Wadi Haifa)

- King Sesurtesen II before a god with two high feathers high feathers (stele found by Burton in Wadi Yesus).

- King Sesurtesen III deified, seated in a sacred processional vessel, worshipped by Tuthmosis III; to the right, the same Tuthmosis stands before the god Tetun, who was worshipped with Sesurtesen in the temple of Semneh from which the depictions are taken. Sesurtesen III, who first pushed the southern border of Egyptian rule as far as Semneh and built fortresses on both banks of the Nile, was later worshipped here as a local god under the honourable title of Lord of Nubia.

- King Amenemhat III before the goddess Hathor, the ‘Lady of Mafkat’ of the Copper Country. This was the name given to the Sinai Peninsula by its copper mines.

- King Sebekhotep V before a jackal-headed god. (Louvre)

- King Sebakem...f in front of the god Khem.

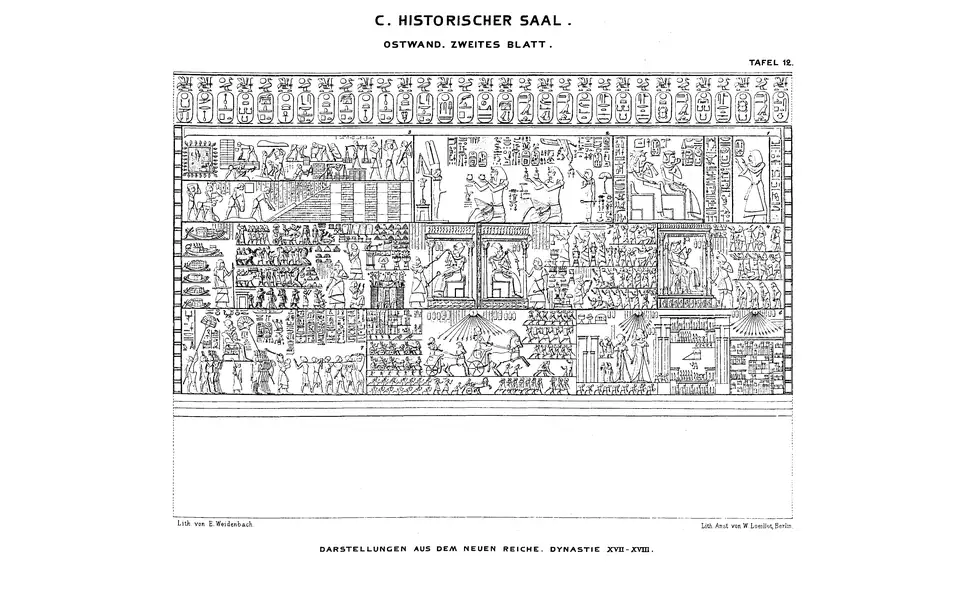

Plate 12

East wall. Second sheet.

The row of cartouches in the frieze contains the Twelfth Dynasty and part of the Thirteenth Dynasty. The depictions are taken from the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Dynasties of the New Kingdom.

- King Amenophis I and his mother Aahmes-Nefretari are worshipped by the owner of a Theban tomb. (LD III, 199.)

- Queen Khnumtamun, her younger brother and co-regent Tuthmosis III, and Princess Ranofru worship the ityphallic Ammon. The queen's cartouches were later changed to those of Tuthmosis; she herself, however, was originally depicted as a man, as in many other images, although her names were all written in the female form. This striking fact can only be explained by the fact that, according to Egyptian custom, a woman could not legitimately rule. She is therefore also ignored in the king lists. (Thebes, Assassif Temple. LD III, 20)

- Foreign slaves paint bricks and build a house, supervised by overseers. The lighter skin colour and the pointed beards easily distinguish the foreigners from the Egyptians mixed among them. There is no justification for taking them for Jews, especially when one thinks of the oppressed Israelites before their exodus. The tribe of Jacob had not yet entered Egypt under Tuthmosis III, under whom the Theban private tomb to which the scene belongs was decorated. Skin colour and beard only indicate that the foreign labourers were of were of Asian origin. (LD III, 40. 41)

- King Amenophis III is enthroned under a canopy. Before him comes the royal scribe Shaemhat with a large retinue; in the top row this official is rewarded with a necklace. (Tomb in Qurna. LD III, 76)

- King Amuntuankh under a canopy receives on the right an Asian envoy under the precedence of the of the ‘Prince of Kush, Hei,’ who was the owner of the Theban tomb from which the depiction was borrowed. This official, as governor of the southerners, carries the staff with the feather as a sign of his high rank. The strangers, clad in costly robes from the shoulders to ankles, are from the Retennu people and bring precious gifts, elaborate vases of gold and silver, horses, a lion and panther skins. Facing left, the same king receives the envoy of a vanquished southern people from Kush. The chieftains of the tribe approach submissively; behind them follow their daughters and sons; the queen herself appears to be brought in on a chariot drawn by oxen. Among the gifts are piles of gold rings and bags of gold sand, animal skins, a giraffe, four live bulls, between whose horns the heads of the guilt victims are probably stuck; and their cut-off hands are attached to the tips of the horns. Next to the king are many heaps of gold rings, gold pouches, elephant tusks and ebony, golden works of art, blankets, skins and a number of beautiful pieces of furniture and weapons, as well as an ornately crafted chariot. (LD III., 115-118)

- Depictions of King Amenophis IV from the rock tombs of Tell el Amarna. The reign of this king towards the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty is a curious episode. He was the son of Amenophis III and his wife Tii. Even as a prince he seems to have been a priest of the sun; at least that is what he called himself in the first years after his accession to the throne. As such, he decided to place the cult of the sun in its simplest form above all other cults that had been derived from it in the Egyptian religion over the course of time. Soon, however, he went so far as to abolish the service of all other gods throughout the country, probably brought about by the opposition of the hierarchy, and even to destroy their names and images wherever they appeared. He gave up his own name Amenophis (Amunhotep), which contained the name of Ammon, who was persecuted above all others, and had it changed to Khuenaten (previously read as Bekhenaten), i.e. ‘Servant of the Sun Disc’, wherever it was already engraved on monuments. He also left his previous residence in Thebes and built a new one to the north in the bay of the valley on the eastern shore, which is now called El Amarna. The tombs of the king's most distinguished officials were dug into the rocks on the eastern bank of the valley, and our depictions are taken from them. On the left is the king in a chariot, behind him the queen (LD III., 92, 93). The sun floats above them, its rays emanating into reaching hands. In front of the faces of the two rulers, the hand offers each of them the symbol of life, which flows in through the nose as living breath. Behind them follow first four princesses on two chariots, then their female court. The procession is surrounded by the king's bodyguard in rapid succession; among them are also some foreign warriors of Asian origin, recognisable by their beards and hairstyles. In the distance you can see the king's palace, which differs from the temples in its ground plan and lighter wooden architecture, and whose light foundations can still be recognised in the ruins of the city, which was destroyed again a few years later. To the right from here (LD III, 101, 102) the king and his wife visit the Temple of the Sun, whose location and most general layout can also still be recognised in the city ruins. The royal couple have entered the first courtyard; the sun shines above them; their daughters follow them. In the second courtyard, which is surrounded by porticoes, stands the high altar in the centre, covered with offerings; a staircase leads up to it. The priest next to him receives the king in a humble position. Behind the third pylon you can see into the innermost chambers of the temple, above which the radiant disc hovers. A colonnade forms the entrance; between the columns, as in the altar courtyard, are the statues of the king and queen. The king and three other people walk up the steps to the rear central chamber; it is the cella, the most sacred room. Only a shrine can be seen in it, in which an image of the sun may be kept. In front of it stands a burning candelabra, the only known example so far of how the Egyptians illuminated their dark temple rooms; for apart from the lamps from the Greco-Roman period, the tombs have not yet revealed any lighting equipment. This king, who was also notable for his physique and facial features and his unprecedented reforms, had seven daughters but no son. The husband of his eldest daughter still appears as king, probably as a short-lived successor. Then the action of the old hierarchy prevailed. All the Puritan king's buildings were destroyed, his residence razed to the ground, his figure and name scratched out on the rock faces, and the images of the old gods restored.

- King Horus on his throne is carried in procession on his shoulders; servants wielding tall fans accompany him; a priest lights incense before him. A line of prisoners from Kush walking in chains before him shows that he is returning home from a southern campaign.

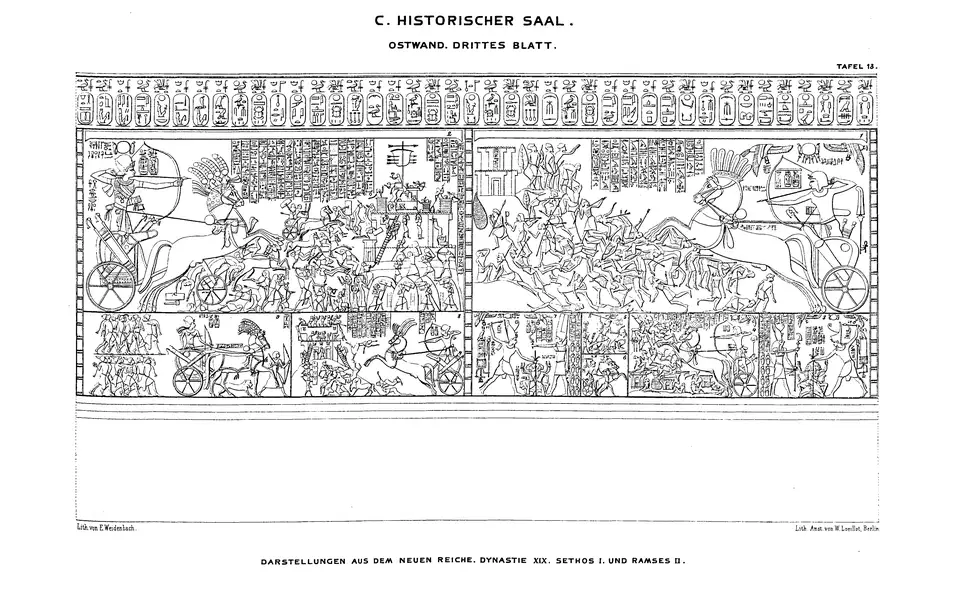

Plate 13

East wall. Third sheet.

The royal cartouches in the frieze date from the Thirteenth Dynasty to King Amenophis III of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The depictions refer to the two greatest pharaohs of the New Kingdom, Sethos I and Ramses II. Both extended Egyptian power far beyond the borders of their country and their names were combined by the Greeks into Sesostris, which sounds like Sethos which was then distorted into Sethosis.

- King Sethos I (Seti) on his chariot defeats the Shasu people; the site of the battle is in Palestine, and inscribed on the tower on the left: Fortress of Kanana. The name Shasu seems to correspond to the Coptic Shos, shepherd, and we are probably looking at the former inhabitants of Palestine in the land of Canaan. The inscription bears the date of the first year of the reign. A gypsum cast of this battle is in the Royal Museum. (Great Temple of Karnak. LD III, 126)

- King Ramses II on his chariot defeats the Asian people of the Kheta. The name Pala is inscribed on the fortress. Seven sons of the king took part in the battle, and one of them is standing on the the ladder, ready to storm the fortress. (Temple Ramses II in Thebes. LD III, 166)

- King Sethos I (Seti) seizes a bunch of enemies by the scruff of the neck to kill them. The god Horns hands him him the weapon Khopsch as a symbol of power and leads him eight conquered Asian peoples to him, among whom among them the Shasu. (Desert temple of Redesieh. LD III, 14.)

- The same king in a battle against the Shasu, who seem to have made a hostile incursion into Egypt. (Great Temple of Karnak. LD III, 127)

- The same king kills some of the leaders of the Libyan people of the Tehennu. Behind him stands his son and successor Ramses. (Temple of Karnak. Rosellini. Mon. Stor. pl. 54)

- Another scene from the same battle against the Tehennu. (ibid.)

- The same king kills a number of enemies from the people of the Kush. Ammon hands him the weapon Khopsh and brings him the representatives of the ten peoples ruled by him. (Desert temple of Redesieh. LD III, 139)

- King Ramses II storms the fortress of Ascalon (Askelena) in Palestine. (Temple of Karnak. LD III, 145)

- The same king returns triumphantly on his chariot; beside him runs his tame lion (or panther?), which Diodorus (I, 48) commemorates. (Rock temple of Abu Simbel. Rosellini, pl. 84)

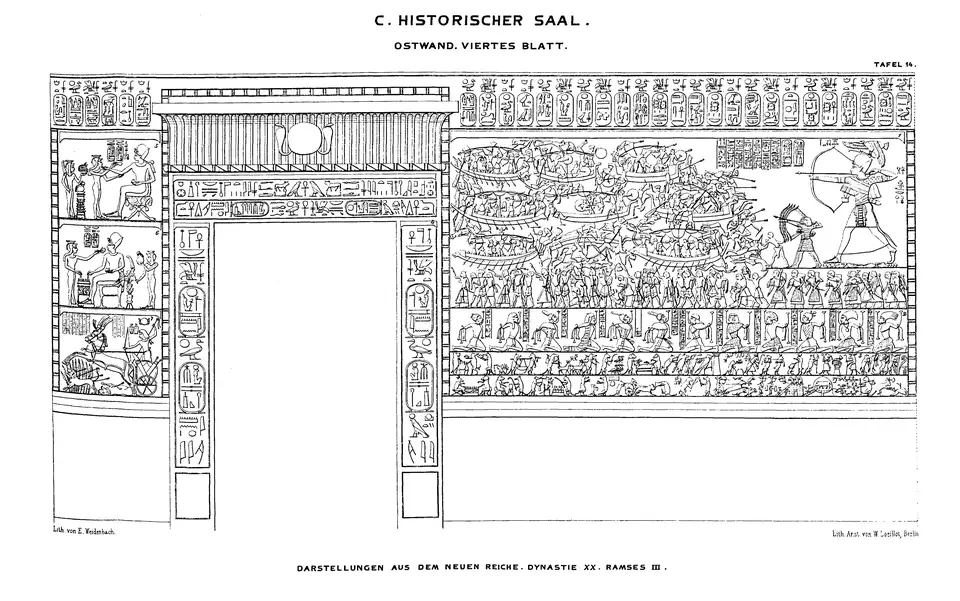

Plate 14

East wall. Fourth sheet.

The cartouches in the frieze date from Amenophis IV in the Eighteenth Dynasty to Menephthes of the Nineteenth Dynasty. The depictions are from the reign of Ramses III.

- King Ramses III (Herodotus' Rhampsinit) stands on the shore of the sea (or the Nile?), on which a naval battle is being waged between the Egyptians and the Fikekero people living to the south. The Egyptian and enemy ships are of the same design and small size; they are equipped with sails, masts, mast baskets and beaks. The enemy are also attacked from the land by archers. The prisoners are carried off in the bottom row. (Thebes. Temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu. Rosellini pl. 131, No. 2)

- A row of prisoners whose heads are so characteristically pronounced that they are probably portraits of captured chieftains. African peoples are depicted on the left, Asian peoples on the right; the two bearded men on the left are Libyans from the north coast of Africa. All have been subjugated by the victories of Rameses III. (Temple of Ramses III in Medinet Habu. LD III, 209)

- A depiction from an ancient Egyptian papyrus has been inserted here, the date of which cannot be precisely determined, but can be placed in the ancient Pharaonic period; it is satyrical and comic in content and shows us a side of the Egyptian character that should not surprise us from other depictions, but which stands out here in a particularly unique way. A musical procession begins at the top right; the donkey plays the harp, the lion plays the lyre, the crocodile the lute and the monkey the double flute. Compare this with the row of four female musicians with the same instruments on sheet 10, no. 17. The donkey then performs a sacrifice before the king of the cats. Below, the cat appears as the guardian of a flock of geese, engages in games with them and is bitten by them. Next to it, the world is shown in reverse, with the hippopotamus sitting on the tree and the eagle climbing up the ladder; then the cats occupy a castle which is besieged by the mice; ladders are put up and the doors smashed down; the mouse king rides up on a chariot drawn by two female dogs. Everything points to a comical imitation of the well-known depictions of war on the temples. Further to the left, the wolf with the sack over his shoulders, blowing the double flute, strides behind the goats as a shepherd, and below him the lion plays checkers with the little goat. The scenes are vividly reminiscent of Homer's Batrachomyomachia and the Adventures of Reineke Fuchs. It is highly probable, as has been demonstrated by others, that the Aesopic and other animal fables originated in Egypt. The papyrus, with hieratic inscriptions and connected to another obscure content, is kept in the Egyptian Museum of Turin. Smaller fragments of another similar one are in the British Museum.

- The inscriptions around the door contain the names and titles of Ramses III, taken from the temple of this king in Medinet Habu.

- 5–7. Three depictions from the front pylon of the temple of Medinet Habu. This building undoubtedly contained the living quarters of King Ramses III, as indicated by all the pictures on the walls. In the two upper depictions, the king caresses his young daughters, receives flowers from them and plays checkers with them. They are characterised as princesses by their side plaits and as immature children by their size and the fact that they are unclothed. The king was wrongly thought to be seen here in his harem. In the lowest field the king appears hunting lions. (LD III, 208)

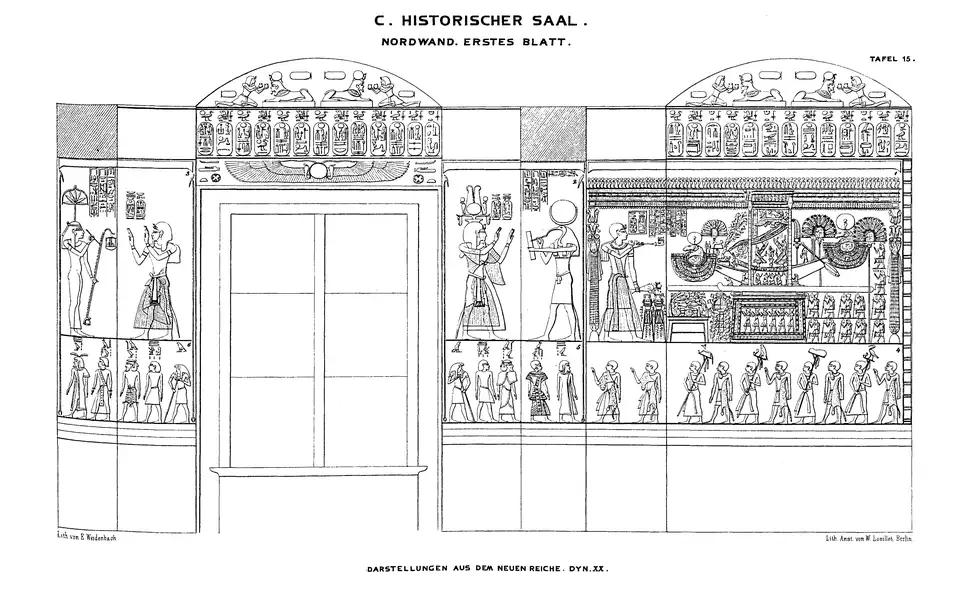

Plate 15

North wall. First sheet.

The cartouches in the frieze lead to Ramses IX of the Twentieth Dynasty.

- Richly decorated sacred barge of Amon Ra, the ‘king of the gods’. The god appears here ram-headed, seated on a lotus flower; the two ends of the ship are decorated with rams’ heads The barque rests on supporting beams, as it was carried around in processions. Below it is a sacred shrine and to the left of it a row of royal statues. Noteworthy are the artificially composed capitals of the columns, which are carved from wood and support the beams. King Ramses IX makes incense offerings and libations in front of the god's barque. (Theban tomb. LD III, 235)

- On the pillar, the ibis-headed Thoth is depicted as the scribe of the gods with a stylus and papyrus, the moon disc on his head. In front of him is Ramses IV in a worshipping position.

- King Ramses XII before Saf, the goddess of history, ‘the mistress of writing, reigning in the hall of books.’

- Procession of priests dressed in animal skins; the sacred jackal, the sparrowhawk, the ibis and a fourth sacred object are carried on poles.

- Representation of the four nations from the tomb of Menephthes. The hawk-headed god Horus strides behind them. First in front of him are the Egyptians, then the Asiatic peoples Aamu, then the Negro Nehesu, finally the Libyans or North Africans Temhu (Rosellini Plates 157-159)

- The same peoples with some changes in dress from the tomb of Sethos I (LD III, 136)

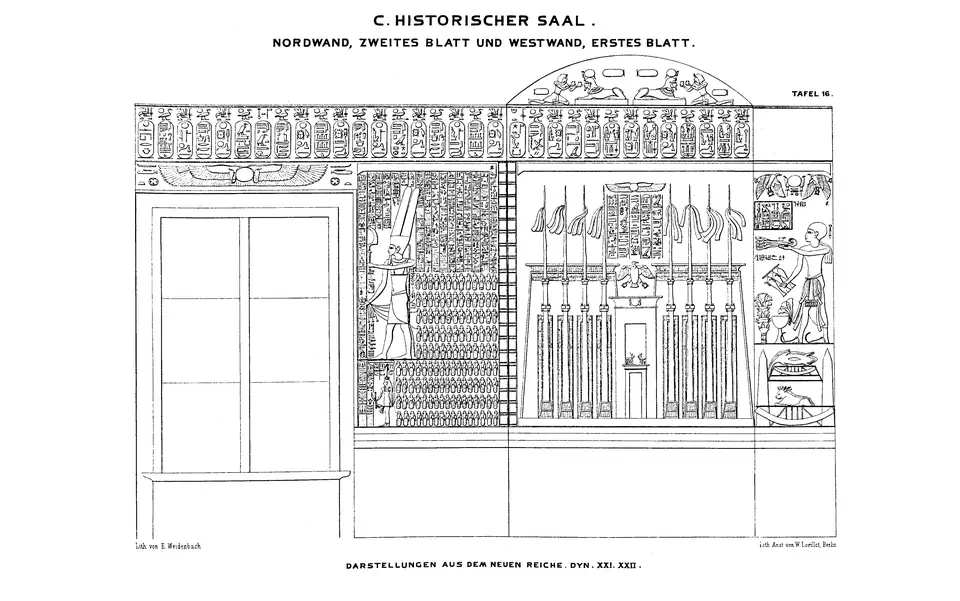

Plate 16

North wall, second sheet and West wall, first sheet.

The cartouches of the frieze lead to Sheshonk (Sesonchis) III of the Twenty-second Dynasty.

- Illustration of a pylon, in the incisions on the front, which can still be seen in most of the surviving pylons, high masts are erected here and decorated with bands at the top. To the right of the pillar, King Herhor of the XXI Dynasty is depicted bringing incense and libations. (Khons temple at Karnak. LD III, 243)

- Amun leads 65 prisoners behind him as representatives of as many landscapes, cities or peoples. Below him, a goddess armed with bow and arrow leads four rows of over 70 prisoners behind her in the same way. The inscription says that Sheshonk I of the Twenty-second Dynasty overcame these peoples. In the third row from the top, the third cartouche reads ‘Juthemalek’, which probably refers to Rehoboam, king of Judah, in whose fifth year of reign Jerusalem was conquered by Sheshonk. (The depiction is found on the southern outer wall of the temple of Karnak. LD III, 252)

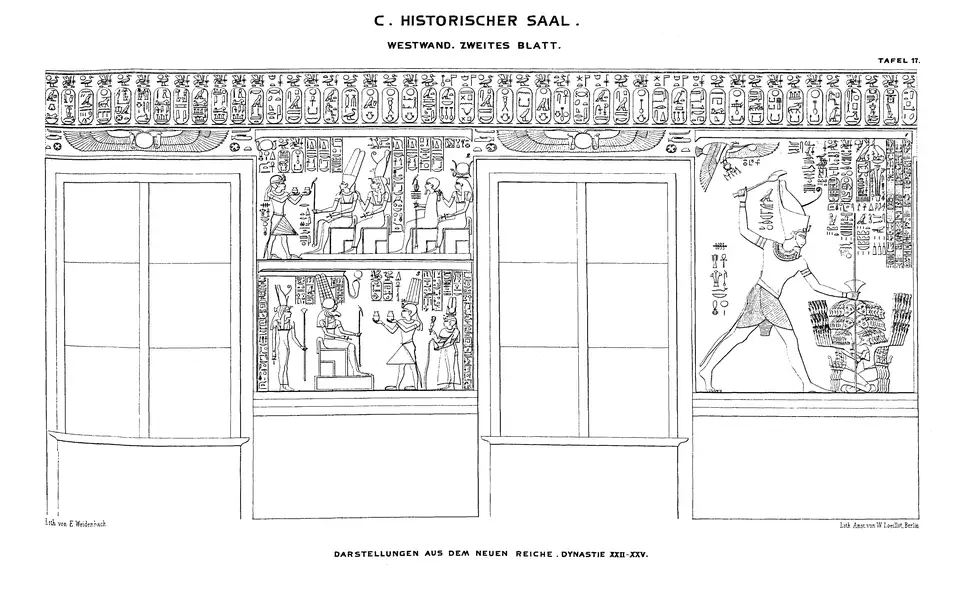

Plate 17

West wall. Second sheet.

Continuation of the cartouches in the frieze up to King Hakor (Akoris) of the Twenty-ninth Dynasty.

- Supplement to the last illustration on the previous page. King Sheshonk I is holding a large number of Asian prisoners by the scruff of the neck in order to kill them. In the original the figure of the king has disappeared or was never there. (LD III, 253.

- King Shabaka offers wine before the Theban gods Amun and Mut, followed by Ptah and Hathor. Shabaka is the Ethiopian Sabacos of Herodotus, who conquered Egypt and ruled it with two of his of his successors. (Karnak. LD V, 1)

- King Tahraka, Thirhaka of the Old Testament, followed by his sister and wife Amuntikhet, sacrifices wine to the ram-headed Amun Ra and his wife Mut. Tahraka was the third and last king of the Aethiopian dynasty, who voluntarily returned to Aethiopia, moved his residence to Mount Barkal and founded a flourishing dynasty there for a number of generations. The ram-headed Ammon remained the chief god of Ethiopia for all time. (Rock temple of Barkal, LD V, 5)

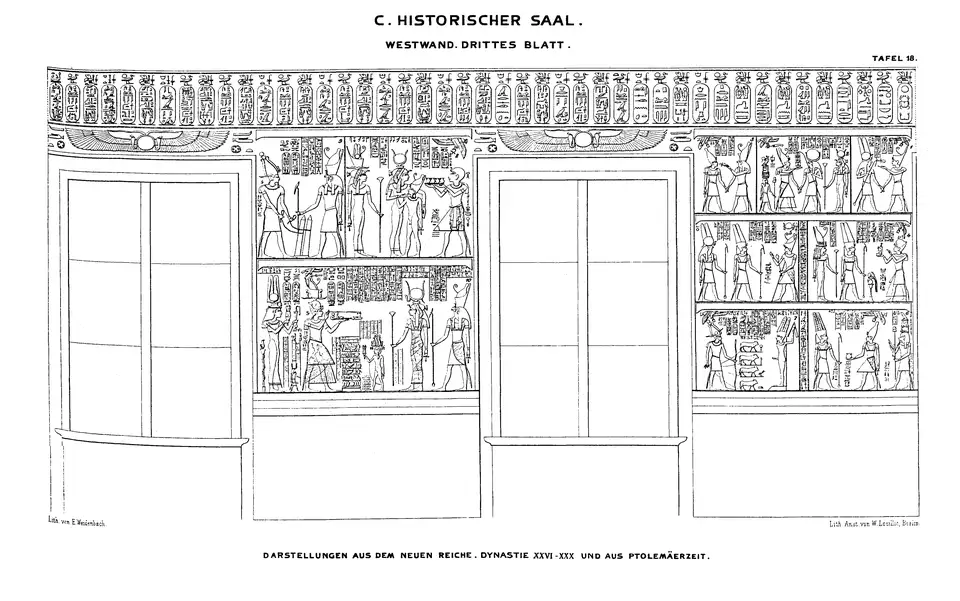

Plate 18

West wall. Third sheet.

The first two cartouches in the frieze belong to Nektanebus (Nekhtnebf), the last king of the native pharaohs. This is followed by three pairs of cartouches from the Macedonian dynasty, Alexander, Philip and Alexander II, followed by the Ptolemies up to Ptolemy XIII Neos Dionysus and his daughter, the famous Cleopatra.

- King Psammetich II of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, worships Montu Ra, the ‘king of the gods’. (Karnak. LD III, 275)

- King Amasis, the penultimate king of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, worshipping the gods Khonsu with a hawk head and a moon disc and Hathor, the Egyptian Aphrodite. (Karnak. LD III, 274)

- Psammetich III receives the symbol of life the hawk-headed Horus , the son of Isis and Osiris. (Karnak. LD III, 275)

- King Nektanebus dedicates a small image to the goddess of justice Ma to Amun Ra and Mut. (Karnak. Bab el Melaha. LD III, 284)

- King Nekhtharheb of the Thirtieth Dynasty worships Amun Ra and Khonsu. (Karnak. LD III, 287)

- King Alexander II, son of Alexander the Great, offers wine to Amun Ra, behind him strides his Genius with the king's standard on his head and on the staff with his torso. (Karnak. LD IV, 3c)

- King Philip (Aridaeus) symbolically leads the four bulls: the coloured, white, red, and black, before the ithyphallic Amun Ra. (Karnak. LD IV, 2b)

- Ptolemaeus Philadelphus sacrifices to Isis, who the young Horus , the divine model of the king, suckles. Behind the goddess stands his sister and second wife Arsinoe II. (Philae. LD IV, 6)

- Ptolemaeus XIII Neos Dionysus dedicates two obelisks to the hawk-headed Horus. ( Edfu. LD IV, 48)

- Ptolemaeus XVI Caesar (Caesarion) offering incense to Isis and her son Horus. Behind him stands his mother, the famous Cleopatra VI. Although still a child, the male offspring takes precedence over his mother, the co-regent. (Great temple of Dendera. LD IV, 54)

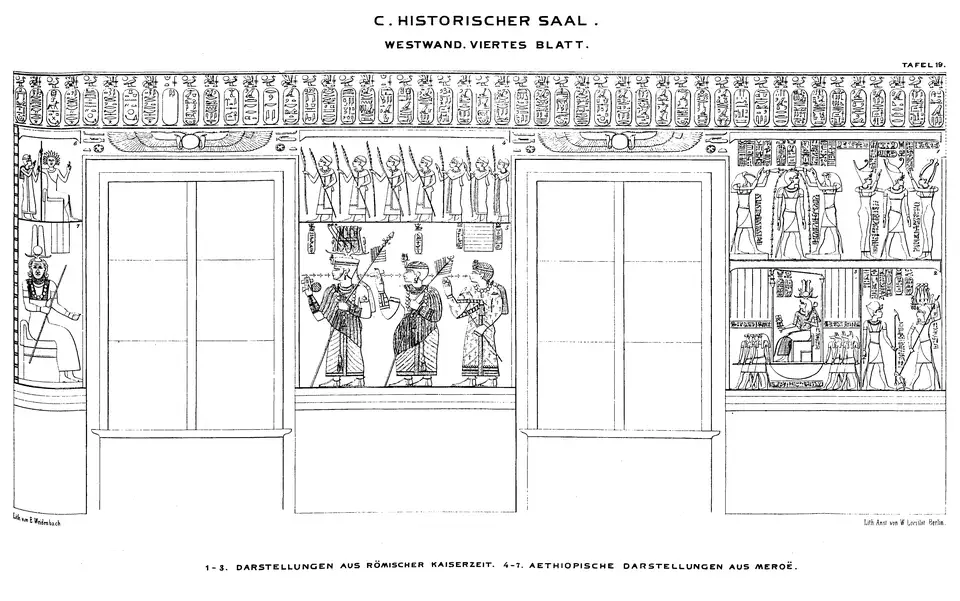

Plate 19

West wall. Fourth sheet.

The series of cartouches begins with Ptolemaeus XVI Caesar and contains the almost uninterrupted succession of Roman emperors up to Decius and Pescennius (?).

- Autocrator Caesar, as the cartouche reads, i.e. Emperor Augustus, stands on the right between the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, who have placed the double royal crown on his head. On the left, the gods Horus (Apollo) and Thoth (Hermes) are depicted above the same emperor. The symbols of life and salvation emanate from the vases above his head. (Great Temple of Philae. LD IV)

- The Emperor Tiberius stands before the god Horus, the symbol of his own rule; he stabs a bound miscreant, symbolising Typhon and all enemies. (Hall of columns of Esneh. LD IV)

-

Emperor Hadrian on a throne under a canopy sitting on a throne under a canopy, is carried in symbolic procession by three hawk-headed

and three jackal-headed gods. (Great Temple of Philae. LD IV)

The following are a number of Ethiopian representations from the late period of this empire, after the kings' headquarters had been moved from Mount Barkal to the island of Meroe, which was surrounded by rivers to the south. While the oldest monuments of the Ethiopian kings under the reign of the successors of the Tahraka show a purely Egyptian style of art, this branch of Egyptian art took on an increasingly wild and barbaric character in the following centuries until the beginning of the Christian era. Thus the sculptures in the pyramids of Meroe and Barkal, and the temples of Naga and Amara, as well as some depictions in the temple of Philae. - Procession of men with palm branches. (Pyramids of Meroe. LD V)

- An Ethiopian king together with his wife and a third royal person, probably the heir to the throne. Remarkable are the fat body shapes, especially of the women, on the Ethiopian monuments. monuments; their clothing and jewellery are rich and their jewellery. The king and queen carry palm sticks scepter, which at the top is wrapped in a simple or the Egyptian cross with a handle, the symbol of life, which ends in a simple or Egyptian cross. Finger rings with cartouches, wider than the whole hand hand, are visible, and the queen carries long, pointed nails pointed nails, like the rich the rich Ethiopian Ethiopian women. (Exterior of a temple at Naga. LD V)

- An Ethiopian god with a crown of rays, a tall staff in his right hand, raising his left hand with two outstretched fingers, his face seen from the front, contrary to Egyptian custom. An Ethiopian king prays and worships him. (Temple of Naga. LD V)

- A god, again the face depicted from the front, with a strong beard and rams' horns on either side of the head, is more reminiscent of a Roman depiction of Jupiter Serapis or similar deities than of Egyptian ones, despite the Egyptian jewellery. (Temple of Naga. LD V)

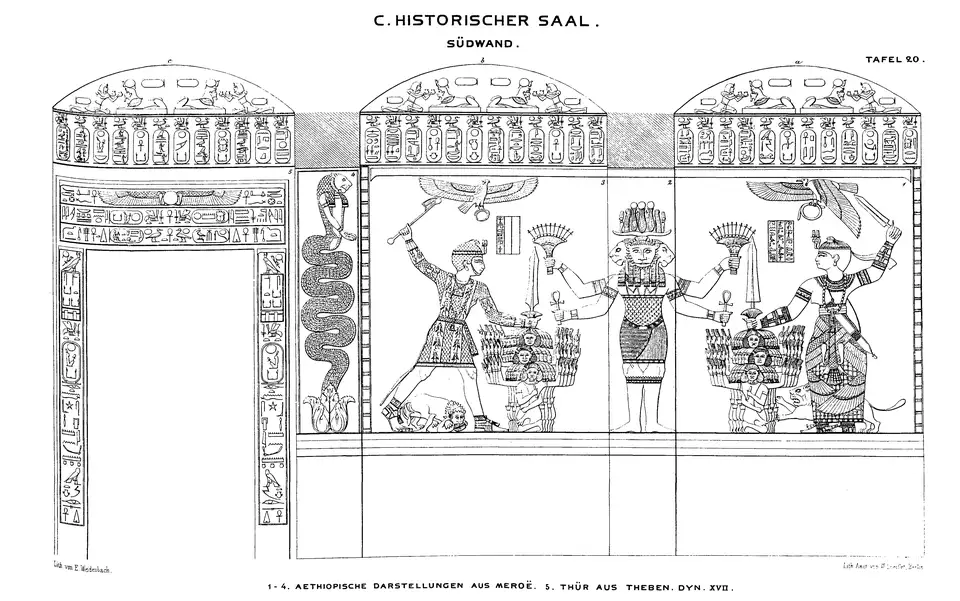

Plate 20

South wall.

The frieze contains the most important cartouches of the Ethiopian monuments.

- An Ethiopian queen in the richest jewellery seizes a group of prisoners by the scruff of the neck according to ancient pharaonic custom and thrusts her sword at them; at the same time they are attacked by a lion accompanying the queen. This queen depicted on the pylon of the temple of Naga appears to be the same as that found on the porch of a pyramid at Meroe, which was largely demolished by the Italian Ferlini, who discovered a treasure trove of massive gold and silver rings and other jewels walled up inside. This treasure of one of the richest and most powerful queens of the Aethiopians, which was exceptionally not attached to the mummy but hidden in the masonry, was largely purchased by the Royal Museum; It contains the only adhesive works of art that have survived preserved from that Ethiopian period. The the strikingly long nails on the hands are noticeable. (Temple of Naga. LD V)

- The pillar depicts a god with four arms and three lion heads, perhaps with a fourth head looking backwards. This deity was foreign to the Egyptians and is more reminiscent of Indian forms, the imitation of which would be nothing marvellous in these times of general religious mixing. (Temple of Naga. LD V.)

- A king beheads prisoners; a lion tears them apart at his feet. The king wears an armoured shirt adorned with figures of the gods. (Temple of Naga. LD V.)

- A royal serpent with a lion's head and arms rises from a leaf ornament. (Temple Naga. Monument. V.)

- The inscriptions around the door contain the cartouches and names of Queen Khnumt Amun; on the right side of the architrave these were later changed to the cartouches of her brother and successor, Tuthmosis III.

Gallery

Photographs of the room

Bibliography

- Brugsch, H., 1855. Reiseberichte aus Aegypten: geschrieben in den Jahren 1853 und 1854. Leipzig.

- Lepsius, C. R., 1849–84. Denkmaeler aus Aegypten. Leipzig. 12 vols. 894 pls.

- Lepsius, C. R., 1855. Königliche museen. Berlin. 21 pp, 37 pls.

- Rosellini, I., 1832-45. Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia. Monumenti storici. 9 vols. 390 pls.

- Stüler, A., 1853. Das Neue Museum in Berlin. Potsdam: F. Riegel. 24 pl.