Before the hieroglyphs were understood, the strange animal-headed gods depicted alongside the mysterious hieroglyphs were thought to be divine messages or magical formulas, rather than the language of a vanished civilization.

The language of ancient Egypt spoken by the pharaohs of ancient Egypt is simply referred to as “Ancient Egyptian.” The language has been extinct for 1500 years and is no longer used for everyday communication. The last vestiges of the language have been preserved in Coptic, but this too has not been spoken for centuries. The modern inhabitants of the Nile Valley speak Arabic — a completely different language.

Ancient Egyptian was based on an alphabet of 24 consonants, not all of which correspond to European alphabets. As in Arabic and Hebrew, the vowels were not written but had to be provided by the reader or speaker. However, there are a number of indications regarding the vowel sounds in Coptic, which is a late form of the Egyptian language that has survived to the present day. When transcribing Egyptian words, the general rule used by Egyptologists was that if there were clues in Coptic, use them, otherwise add an ‘e’ to the words until you get something pronounceable to European ears. The transcriptions were made mostly by English, French and German Egyptologists using their own language, resulting in wide variations of the names of the pharaohs.

Scribes were highly educated individuals who were responsible for record-keeping, drafting legal documents, and maintaining religious texts. For the majority of Egypt's history, three distinct scripts were in use. The most common was Hieratic, used for everyday transactions like inventory, wages and tax records. Artisans also used hieratic to mark their finished products. Cursive Hieroglyphs were reserved for religious texts, while Hieroglyphs were used for inscriptions on monuments erected in honour of kings and other prominent figures. Hieratic writing was mostly done in ink on papyrus, while hieroglyphs were carved onto more durable materials such as stone, metal, wood, and so on.

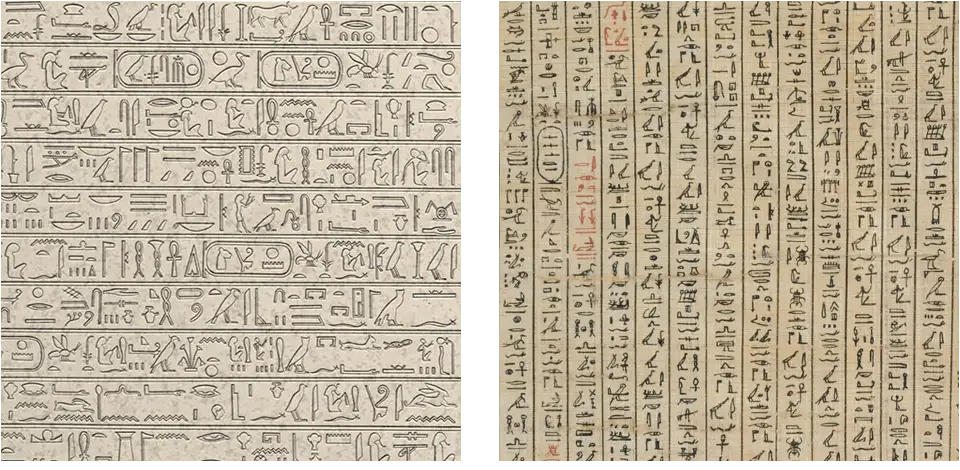

The art style of Ancient Egypt is very distinctive, always depicting humans in profile, except for the torso, which is seen from the front. This art was almost always accompanied by smaller symbols of animals, tools, plants and more. However, these were not just symbols, but a highly formalized script and language: the hieroglyphs.

Hieroglyphs

Thanks to a large collection of preserved writings, the deciphering of the hieroglyphs in the early 19th century revealed that the mysterious hieroglyphs

were actually an extinct language. The Ancient Egyptian language went through several stages of development known as Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, and Demotic. These stages correspond to different historical periods.

Thanks to a large collection of preserved writings, the deciphering of the hieroglyphs in the early 19th century revealed that the mysterious hieroglyphs

were actually an extinct language. The Ancient Egyptian language went through several stages of development known as Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, and Demotic. These stages correspond to different historical periods.

The ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs were primarily used for monumental purposes, carved in stone, and often very ornate and painted in vivid colors. This was not at all suited for everyday purposes as it often required artistic skills and production was both cumbersome and time-consuming.

The word ‘hieroglyph’ comes from the Greek

The texts can be divided into two stages: Earlier Egyptian, basically all written texts from before 1400 BCE, and Later Egyptian, i.e. all later texts, including most surviving papyri. Earlier Egyptian can be subdivided into Old and Middle Egyptian, while Later Egyptian can be subdivided into Late Egyptian, Demotic and ultimately Coptic.

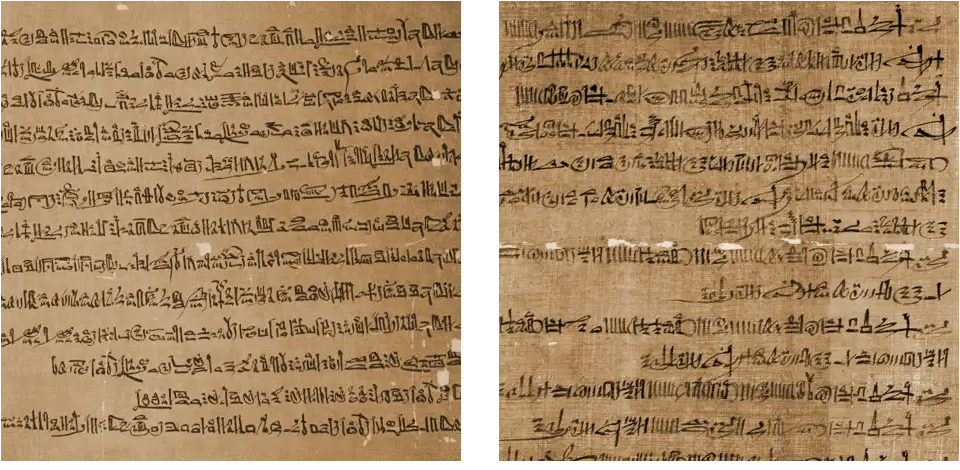

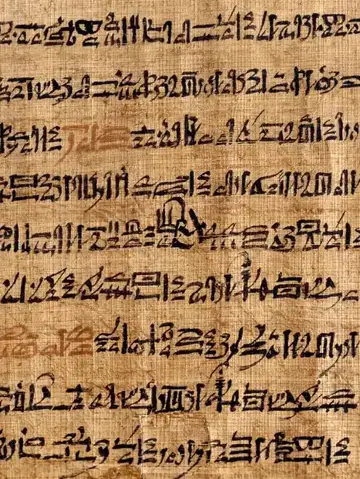

Writing on stone is unforgiving of mistakes and time-consuming in the long run, and a growing government was demanding something a lot easier and faster. The papyrus plant was abundant in the Nile delta, and already used to make baskets, rope and much more. The idea of using papyrus as a writing medium was nothing short of revolutionary. A system was soon devised, using a reed brush dipped in ink to write hieroglyphs on the papyrus. Writing elaborate hieroglyphs in ink is very impractical, and a simplified script that retained the form of the hieroglyphs, but was easier and faster to write soon emerged: Cursive Hieroglyphs. But even this was still slow, and not suited for everyday administrative purposes, so an even faster and more simplified system came into being: Hieratic.

As papyrus and ink were much better suited to the increasing daily volume of documents required by the administration of the kingdom, hieratic writing was undoubtedly one of the most important developments in ancient Egypt. Cursive hieroglyphs continued to be used, but mainly for important religious texts such as the Book of the Dead.

Hieratic was written horizontally, from the right side to the left. Hieroglyphs could be written vertically, facing left or right, or horizontally, from left to right, or from right to left. Hieratic continued to be used throughout Egyptian history, but by the seventh century BC, changes to the Egyptian language demanded and required a script with standardized sign groups, which turned into Demotic. Both were used, Hieratic for religious purposes and Demotic for everyday use, such as letters, legal papers, and invoices.

Throughout the long history of Egypt natural variations appeared in the hieratic signs themselves, but they were still similar and understandable. As time went on, hieratic came to feature more and more insignificant flourishes and ornamental parts used only to fill empty spaces.

Later dynasties revered the language of the Old Kingdom and strived to imitate the monumental texts, resulting in a highly formalized archaic language that saw very little change throughout Egyptian history. After the conquest by Alexander the Great, hieratic and Demotic were slowly supplanted by transcriptions of Greek characters incorporating Demotic signs for Egyptian phonemes. This final version of the Egyptian language is known as Coptic. The Coptic alphabet (ⲁⲃⲅⲇⲉ ⲍⲏⲑⲓⲕⲗⲙ ⲛⲟⲡⲣ ⲥⲧⲩⲫ ⲭⲯⲱϣ ϥϧϩϫϭϯ) remained in use in Egypt until the Muslim conquest of the seventh century, when it was replaced by Arabic as the written language of daily life. The spoken language itself proved somewhat more resilient, surviving for centuries despite the Arabic hegemony.

Deciphering the hieroglyphs

In the fifth century BC, Herodotus wrote in Histories 2.36 that

“The Greeks write and calculate from left to right; the Egyptians do the opposite; yet they say that their way of writing is towards the right, and the Greek way towards the left. They [the Egyptians] use two kinds of writing; one is called sacred (From these Greek words, we derive the terms hieratic and Demotic. At the time, it was not known that Demotic was a simplified form of Hieratic, which was used only from the latter part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty onwards. Four centuries later, Diodorus wrote in Bibliotheka 1.81:ἱρὰ , hira), the other common (δημοτικὰ , demotika)”

“In the education of their sons the priests teach them two kinds of writing, that which is called sacred (ἱερὰ , hiera) and that which is used in the more common (κοινοτέραν , koinoteran) instruction.”

and expanded upon it slightly in Bibliotheka 3.1.5:

“... for of the two kinds of writing which the Egyptians have, that which is known as popular (δημώδη , demodi) is learned by everyone, while that which is called sacred (ἱερὰ , hiera) is understood only by the priests of the Egyptians, who learn it from their fathers as one of the things which are not divulged.”

It is evident that there has been a failure to communicate accurate knowledge of the scripts. The precise cause of this failure is unclear, though it is likely to have resulted from a misunderstanding or misinterpretation:

We must now speak about the Ethiopiansic writing which is called hieroglyphic among the Egyptians, in order that we may omit nothing in our discussion of their antiquities. Now it is found that the forms of their letters take the shape of animals of every kind, and of the members of the human body, and of implements and especially carpenters' tools; for their writing does not express the intended concept by means of syllables joined one to another, but by means of the significance of the objects which have been copied and by its figurative meaning which has been impressed upon the memory by practice. (Bibliotheca Historica 3.4.1)

More than four centuries later, Ammian wrote about the hieroglyphs on obelisks in Res gestae, showing that true knowledge about the hieroglyphs was still available, although it was slowly slipping into obscurity.

Now the infinite carvings of characters called hieroglyphs, which we see cut into it on every side, have been made known by an ancient authority of primeval wisdom. For by engraving many kinds of birds and beasts, even of another world, in order that the memory of their achievements might the more widely reach generations of a subsequent age, they registered the vows of kings, either promised or performed. For not as nowadays, when a fixed and easy series of letters expresses whatever the mind of man may conceive, did the ancient Egyptian also write; but individual characters stood for individual nouns and verbs; and sometimes they meant whole phrases. (Res gestae XVII.4)

By the middle of the fifth century, when the last (mostly inaccurate) vestiges of knowledge were collected in Horapollo's Hieroglyphica, the Egyptian language was no longer understood. This meant that the ability to read and write hieroglyphs, together with hieratic and demotic, was completely lost. Knowledge about the hieroglyphs faded from memory during the Middle Ages, and when interest was revived during the Renaissance, scholars relied on faulty information from Greek and Roman sources. These sources portrayed Egyptian writing systems, particularly hieroglyphs, as mystical symbols rather than a way to record spoken language. This assumption made deciphering any attempts destined for failure. That changed in the mid-1600s, when the German scholar Athanasius Kircher made the first attempt to translate hieroglyphs, assuming that they were phonetic characters.

When the Rosetta Stone was uncovered in Egypt in 1799, it looked like decipherment was only a few steps away, as it contained a trilingual text in hieroglyphs, Demotic and Greek. At the time, it was not understood that hieroglyphs, hieratic, Demotic, and Coptic represented distinct stages of the Egyptian language. Moreover, early 19th century researchers were forced to rely on transcriptions of the ancient scripts that were of an extremely poor quality. Indeed, the majority of reproductions were not accurate representations of the original texts.

Several researchers contributed to the consolidation of information about the ancient Egyptian language and associated scripts throughout the course of the following 25 years. As noted above, according to the historians of antiquity there were two Egyptian scripts, hieratic and Demotic.

In 1821, the French scholar Jean-François Champollion noticed that some of the texts thought to be Demotic were in fact written in a similar but different script. After extensive research he proved that it had to be hieratic, as it was similar to both hieroglyphs and Demotic, but distinct from both. The discovery was a very important step in solving the mystery of hieroglyphs, as hieratic papyri would provide a secondary source for many texts from Egypt.

Champollion published his Summary of the hieroglyphic system in 1824 providing the key to reading hieroglyphs, and establishing beyond doubt that the hieroglyphs themselves were composed of both phonetic and ideographic elements. Over the next few decades scholars verified and improved on Champollion's system, finally revealing the exact nature of the hieroglyphs. The next generation of explorers understood and embraced the importance of accurately reproducing the ancient texts.

Egyptian hieroglyphs consist of three types of glyphs:

- Phonetic signs — including alphabetic characters.

- Logographic signs — representing a word, or part of a word; like how the % sign equals the word 'percent'.

- Determinative signs — placed at the end of logographic or phonetic words, narrowing down the meaning.

The titulary of the pharaohs were almost never reused, but created specifically for each king upon ascension.

Transliteration

In transcription, (a written representation of a spoken language) a, i, and u all represent consonants; for example, the name Ramesses was written in Egyptian as Ra-msi-sw. As a matter of convenience, experts have assigned generic sounds to a, i, and u, which is an artificial pronunciation that should not be confused with how Egyptian was actually pronounced at the time. As the hieroglyphs contain no vowels (as such), an "e" is generally inserted between the consonants to form readable words.

It is not possible to translate hieroglyphs directly; first, the hieroglyphs must be converted into alphabetic writing, a process known as transliteration, which employs numerous letters not typically found on keyboards:

Since there is no easy way to write them, Manuel de Codage (MdC) was developed, which is a standarized system for transliteration of hieroglyphic texts on computers makes this much simpler, by converting the characters above and substituting them with normal alphabetic characters.

| Transliteration | |||||||||

| Manuel de Codage | A | a | H | x | X | S | q | T | D |

Gardiner’s Sign List is a comprehensive list of 763 commonly used hieroglyphic signs ordered into 26 categories for occupations, birds, mammals, trees, furniture etc. It was initially compiled by renowned Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner in 1927, and is still in use today. Manuel de Codage incorporate Gardiner’s list to reference specific hieroglyphs.

The hieroglyph for the sun, ⊙ (Ra) is designated as N5, part of Gardiner category N which relates to the sky, earth and water.

Hieroglyphs, unlike alphabetic scripts, can be placed above each other, or form groups of signs called ligatures. They can be written from left to right, or right to left, or even vertically from the top. The reading direction always follow the direction the signs are facing, left or right. Manuel de Codage also incorporates features to change size, orientation, colour and placement of signs. This is necessary to be able to place the signs exactly in their correct position in relation to each other.

An example.

To translate hieroglyphs there are a couple steps to go through. Consider these hieroglyphs:Firstly we need to separate each of the 13 signs, then we can begin the translation process:

Hieroglyphs →

Transliteration →

Transcription → netjer-nefer za-Ra imn-Htp ankh wedja seneb

Translation → The Good God, Son of Ra, Amenhotep, Life, Prosperity and Health

As Manuel de Codage includes options to add cartouches, grouped signs, 2-dimensional positioning of signs, and much more, the encoded text above becomes:

Manuel de Codage → nTr-nfr-zA&ra-<-i-mn:n-Htp:t*p->-anx-DA-s

Gardiner numbers → R8-F35-G39&N5-<-M17-Y5:N35-R4:X1*Q3->-S34-U28-S29

Amenhotep is transliterated

Software

I recommend JSesh Hieroglyphic Editor by Serge Rosmorduc, which, in my opinion, is the best editor to use for hieroglyphic texts of any kind, and it is not very hard to learn to use. It is available for Windows, Mac and Linux and is completely free! You can even copy and paste the hieroglyphs straight into your Word documents, or, export them as JPG, PNG or SVG files or many other formats.

Manuel de Codage

The first printed version of MdC was published in 1988, basically the Stone Age of computing. A slightly altered version was published online in 1997 at Utrecht University Centre of Computer-aided Egyptological Research (CCER), a project which no longer exists, though the Internet Archive have snapshots of the page from 2001 here. A copy of the page can be found here, and if that vanishes too, it is archived here.

Manuel de Codage is far from perfect however, there are a number of minor annoyances that has been rectified in an updated specification called the Revised Encoding Scheme for hieroglyphic (RES) which has been under (stalled?) development since 2002, but I have found no indication that it has been accepted as the "new" standard. The documentation can be found at The RES-project. There have been several projects over the year, but sadly it always lead nowhere.

How early Egyptologists preserved hieroglyphs

For some reason, the following information is difficult to find described in the academic reference works about hieroglyphs—instead, it is assumed that you already know it.

Scribes used black ink on papyrus, with certain (important) signs written in red ink. When Egyptology was still young (i.e. in the 1800s), books and journals were almost universally printed in black and white, and the early Egyptologists often wrote journals by hand. To differentiate red signs, they came up with an elegant solution: by simply underlining them. They quickly realized that dealing with crumbling monuments or papyri, exact annotation is crucial to preserve the text to minimize any ambiguity. This is extremely important since numerous hieroglyphic texts suffered damage or were lost following their discovery, making older publications crucial to preserving the content.

The special brackets described below were used for copying and transcribing hieroglyphs. This allows us to notice the nuances in texts copied by early pioneers, especially since their work preserves texts that have deteriorated beyond readability or been lost entirely.

When comparing two similar texts, horizontal arrows pointing left and right ←→ in place of hieroglyphs indicate that the missing signs were intentionally omitted.

Hieratic

Hieratic writing was a cursive script of simplified and connected characters used in ancient Egypt. It could be written quickly on papyrus, making it practical and very suitable for everyday use, unlike hieroglyphs, which took a long time to write. It was mainly used for religious, administrative and literary texts.

The scribe would carefully copy the text from the original source onto the prepared papyrus following a predetermined layout and formatting, replicating the organization of the original text. This process required precision and attention to detail to avoid errors and might involve the use of columns, headings, and other structural elements.

In some cases, especially for religious or important texts, the scribe might include decorative elements and illustrations. These could range from simple designs to elaborate scenes. After completing the copy, the scribe might review the text for errors. Corrections could be made directly on the papyrus, and in some cases additional notes. Once the copying and corrections were done, the papyrus sheet could be rolled into a scroll if the text was lengthy.

The production of copies involved manual reproduction by scribes. Each copy was produced individually, and skilled scribes were valued for their ability to create accurate and aesthetically pleasing duplicates. In some cases, workshops specialized in the reproduction of texts. Multiple scribes could collaborate in such workshops to produce copies more efficiently. Copies of texts were distributed to various locations, including temples, libraries, and private collections. This dissemination contributed to the preservation and accessibility of important literary, religious, and administrative texts.

Copying manuscripts by hand is a meticulous task, and scribes could make unintentional mistakes. These errors might include misspelling words, omitting or duplicating lines, or misinterpreting the original text. Over time, papyri deteriorate due to exposure to the elements, pests, or simple aging. This can lead to the loss or distortion of text, making it difficult to accurately interpret the original content. In some cases, individuals may intentionally alter or forge a manuscript to serve a particular agenda or to create a more valuable document. This could involve adding or removing content, changing the wording, or modifying details to suit the forger’s purposes.

Papyri are also vulnerable to damage from water or fire, which can result in the destruction or alteration of the text. Water damage may cause ink to run or pages to stick together, while fire damage can char or consume portions of the manuscript. The quality of ink used can affect its longevity. If the ink fades or bleeds over time, it can make the text illegible or altered.

Insects can damage papyri by feeding on it, leading to the loss of content. Additionally, their excrement can stain or obscure the text. Mold and mildew can grow on papyri, especially if stored in damp conditions. This can result in the decay of the material and make the text difficult to read for example, tearing, folding, or creasing pages can result in the loss of text or make it challenging to decipher.

Learning to read & write hieroglyphs

Manley’s Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Complete Beginners is an excellent place to start to learn to read hieroglyphs. It will give you a peek into hieroglyphics, to see if learning to read hieroglyphs is something you really want to do. It will require a lot of time—the books are listed in order of difficulty, each step becoming more difficult, but also more detailed and illuminating. The last two volumes are purely academic work, and require a good understanding of hieroglyphics.

- Bill Manley. Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Complete Beginners. 2012.

- Mark Collier and Bill Manley. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Step-by-Step Guide to Teach Yourself. 1998.

- Janice Kimrin. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs : A Practical Guide. 2004.

- James P. Allen. Middle Egyptian An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. 2010.

- James A. Hoch. Middle Egyptian Grammar. 1997.

Bibliotheca Alexandrina is recommended for more detailed information, including lessons on reading hieroglyphs.

Even more details and information on all things Egyptology can be found at the

Egyptologists’ Electronic Forum (EEF).