The original fragments of the Royal Papyrus of Turin

Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac

1851

English translation of “From the manual table of the kings and dynasties of Egypt or the Royal papyrus of Turin, its original fragments, its manuscripts or printed copies, and its interpretations” published by J. J. Champollion in 1851. Only the first two articles are translated here, as the two remaining articles concerning the contents are outdated and of little interest. A plate with the fragments by J-F Champollion is at the end.

First part, pages 397-402

The onomastic and chronological Egyptian manuscript, known as the Royal Papyrus of Turin, has excited attention of the learned world, for twenty-five uninterrupted years, which recognized its importance from the moment of its discovery. It is one of the oldest and most useful historical documents that came to us from the ruins of the Orient.

I have proposed to summarize the most interesting data concerning this papyrus; its origin, its history, the known manuscript facsimiles, and other copies which are not yet known, and those which have been published. In a word, to explain what has been done with regard to this rare ancient document, and what remains to be done for the advancement of studying the primitive times of the Egyptian annals.

To be brief, I shall not attempt to examine the many passages one by one in the various books where the Royal Turin Papyrus is mentioned,[*] and in the interests of sometimes very opposing views, I do not raise the point, one by one, errors or omissions you notice in some of these works, on some points in the history of this book that I call Tables of the dynasties and kings of Egypt. I will gather the facts and evidence here to present the true history, and science can now save themselves the trouble to look elsewhere for the evidence: I will follow the order of time.

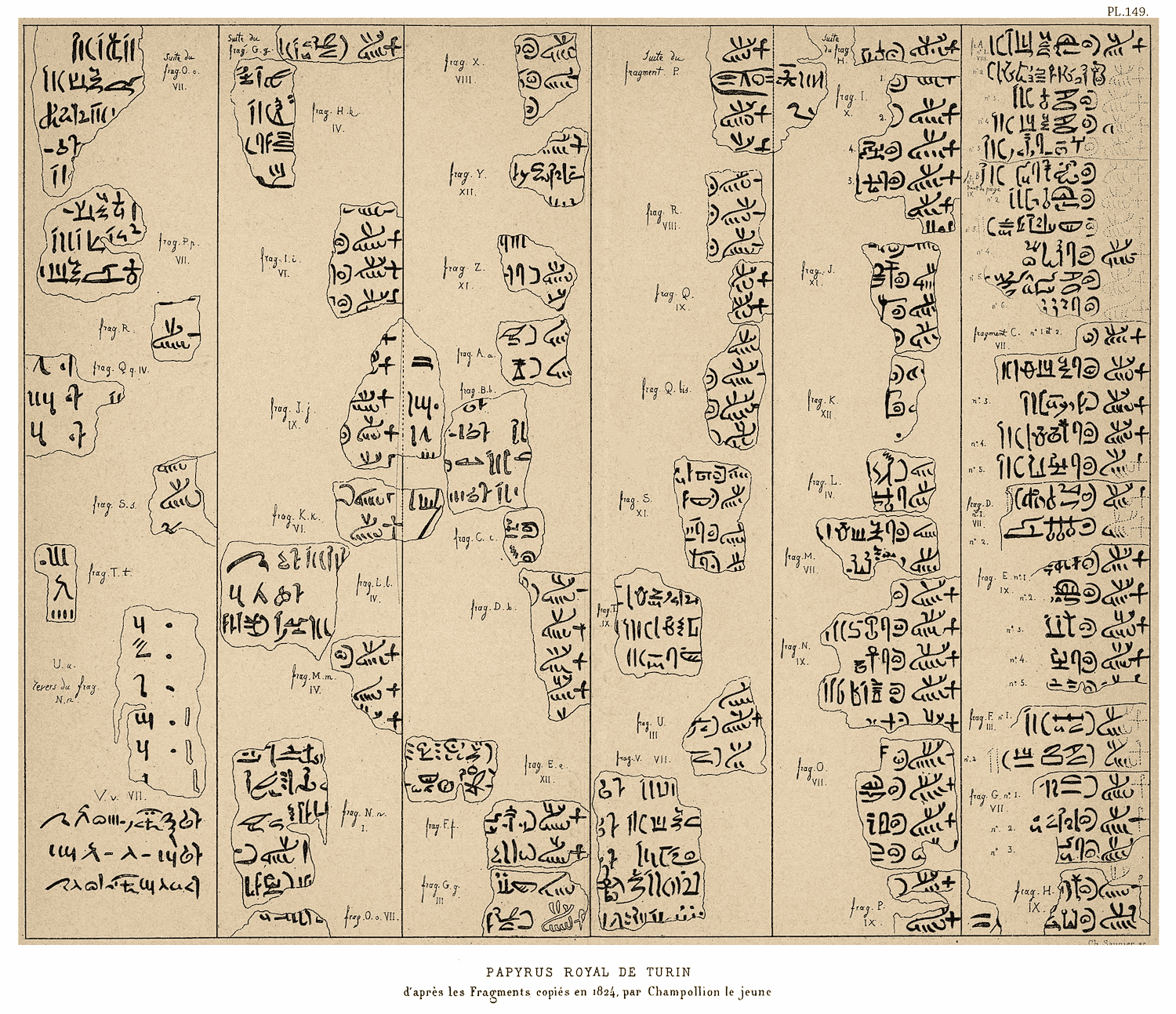

Nothing is better known among archaeologists than the collection of Egyptian monuments, which was gathered by the late Drovetti, Consul General of France in Egypt. A collection offered to the French Government in the year 1818, that was rejected, and soon after acquired by the king of Sardinia. It is the main part of the Royal museum of Turin; The manuscript that we are dealing with comes from this Drovetti collection. (See Plate 149.)

It was in 1824 that Champollion the younger recognized the fragments of this manuscript in a considerable mass of debris from other documents also written on papyrus. The announcement was made public in the Bulletin Universel,[*] in November the same year, 1824, by a short extract of a letter that the French scholar wrote to me from Turin on the sixth of the same month.

I give here the complete and unpublished text of this letter:

“All the manuscripts, of which I have examined the texts, are in hieratic writing, and most of them true models of calligraphy. Not one of the names of kings is after the Nineteenth Dynasty, and the mass of these manuscripts shows that the one who discovered them has found the entire archives of a temple.”

“But the most important papyrus, of which I shall always regret the complete fragmentation, and which was a real treasure for history, is a chronological table, a true royal canon, in hieratic writing, containing four times as many dynasties than the Table of Abydos had originally. I recognized, in the midst of the dust, some twenty fragments of this precious manuscript, only an inch or two at most, containing however, more or less fragmented names of seventy-seven pharaohs. What is most remarkable in all this is that none of the names of these seventy-seven Pharaohs resemble those of the Abydos Table, and I am convinced that they all belong to the earlier dynasties. It also seems certain to me that this historic canon is from the same time as the other manuscripts, among whom I have collected the debris, that is to say, that is not later than the Nineteenth Dynasty.[*] This is another discovery which cause as much regret as pleasure.”

In another letter of the 15th of November, 1824, my brother returned again on this subject in these terms:

“I have finally finished examining the remains of the hieratic manuscripts, and have been fortunate enough to find a number of other fragments of the royal canon. I say royal canon, since several pieces of this invaluable manuscript prove that it was divided into columns of royal names, followed by the number of years of the reigns, expressed in hieratic figures. But unfortunately, there are only fragments of about forty, which are difficult to connect with each other, which proves the extent of this papyrus, of which there remains only the smallest part. An abundance of historical information which might have been obtained, if the barbarians had not torn it to pieces. I found some royal names written in red ink in the midst of the other names traced in black: I presume that these were chiefs of dynasties. In the end, I collected among the remains of this royal canon, which was a veritable Manetho in hieratic writing, about one hundred and sixty to one hundred and eighty royal names. Many are complete, but many are also truncated, either at the beginning or at the end. A number follow each other, which will always be a means of chronological classification. I am sending you a copy of these precious fragments.”

“The most striking result of this exhumation is undoubtedly the acquired proof that the Egyptians, at a very remote period, as this text was found in the midst of fragments which do not belong after the Nineteenth Dynasty, counted nearly two hundred reigns before the Eighteenth Dynasty. In all these fragments of the royal canon there is not a single cartouche similar to those of the kings of the Seventeenth, Eighteenth, or subsequent dynasties. Consequently, an important fact can be drawn from this. Manetho numbered thirty Egyptian dynasties, and this shows that the antiquity of the Egyptian nation was in full force in the twelfth century before the Christian era.”

In his second letter to the Duke of Blacas, relative to the Royal Museum of Turin, and published in 1826, Champollion said (p. 43):

“Despite the almost complete destruction of these hieratic manuscripts, I have put together a number of protocols from public documents, of different reigns and some fifty fragments of a papyrus, the most precious of all no doubt: it is a timeline of Egyptian dynasties which I will speak more of in a future letter.”

These are the first, the oldest, and the most authentic records of the papyrus of Turin. It is still in the same state of degradation, as Mr. Barucchi taught us, “il qual papiro sebbene presentemente è ridotto a moltissimi e minuti frammenti”.[*] There are, in fact, as many as one hundred and sixty-four blank or written fragments, some of several inches, others not even a square inch; and as to the judgment on merit and the period of this manuscript, nothing has been added to what Champollion said in his letters of 1824 and 1826.

It may be noted in passing that Rosellini who, despite the letters Champollion published in 1824 and 1826, said in 1832 that it was a German scholar, Mr. Seyffarth, who managed to discover, “pervenne a scoprire”, that many of these fragments of papyrus belonged to a catalogue of names of kings with the date of their reigns.[*] This is one of the usual testimonies of gratitude of Rosellini to his dearest teacher.

The public, and so unexpected, announcement of Champollion’s discovery of a historical document of this nature, touched the minds very differently; excitement in the learned world, joys and regrets even, it has been said. The existence of this precious document, and it is added, that it was indeed removed for some time from curiosity or public scrutiny. It is certain that immediately after this announcement in 1824, a considerable number of remaining Egyptian manuscripts were concealed from Champollion, and that he could not continue his researches and discoveries, being ignorant about their existence.

Shortly afterwards, in 1826, the learned German gentleman, who was also occupied with the study of Egyptian antiquities, Mr. Seyffarth, went to Turin, saw the fragments of the royal papyrus, applied himself to bring them together, and made a copy of the whole, where he classified each fragment as best he could. He recomposed and restored an uninterrupted series of successive reigns, having the appearance of a whole royal cannon. This Restoration was based solely on natural lineaments, and the joining of those fragments which seemed to be able to be mutually joined. Mr. Seyffarth has at length exposed the elements of this method of restoration of the Egyptian papyri in his prodigious Systema astronomiae aegyptiacae (p. 203), where, although the publishing in 1833, he does not say a word about his restoration of the royal papyrus.

This entirely mechanical process did not prevent the inconvenience of the lacunae, but Mr. Seyffarth had confidence in his own knowledge. With these means alone, he took a second look and rebuilt a roll of twelve columns or pages, each having twenty-six to thirty lines. Reducing the lines to thirty or so, containing the names of the gods or kings, in which we only read numbers. Mr. Seyffarth communicated this work to several scholars, and there are copies of them. Rosellini, who knew him, did not think fit to use it; he publicly gave the reasons for this resolution: he believed that each king’s name was isolated on a fragment of papyrus, and he did not think that the reconstruction of the list, nor the method of the German scholar was sufficiently reliable to be authoritative.

Mr. Dulaurier, a professor at the Special School for Living Oriental Languages, had seen one of the copies of Mr. Seyffarth’s work, and made a duplicate, which he then copied for Mr. Samuel Birch, who hastened to give his copy to the Egyptian collection of the British Museum, of which he is the curator. Soon after, Mr. Birch published a short notice,[*] with the facsimile of the first page or first column of the papyrus thus restored. When Champollion was in Turin in 1824, having recognized and assembled all the original fragments he was allowed to see, numbering forty-six; he did not at first undertake to re-establish them in their original order; he contented himself with making minutely faithful copies of each isolated fragment. He then transcribed them, in part, into a notebook, distinguishing each fragment by a letter of the Latin alphabet; the largest of these fragments bears six names of kings in succession. (These two copies are now in the government’s collection.) We shall soon see how useful they are to science.

Dr. Lepsius, well known for his numerous works on Egyptian archeology, saw the royal papyrus at Turin in 1835. He was told of the zeal and efforts of Mr. Seyffarth, the care with which he had collected the fragments, which Champollion had not seen; and he made a drawing of the whole, but did not find any of the fragments the French scholar had examined and transcribed.

Three years later (in 1838), Mr. Lepsius was in Paris; I disclosed to him the copies of the isolated fragments of the papyrus made by my brother. In London he also saw, shortly afterwards, in the hands of Mr. Birch, the copy made by Mr. Dulaurier of Mr. Seyffarth, and Mr. Lepsius then learned that the first page of the original papyrus had been unknown to him when he made his copy in Turin.[*] Mr. Bunsen, who recalls in the first volume of his learned work (Ägyptens Stelle, p. 83) the communication which I made to Mr. Lepsius and that of Mr. Birch, adding that Mr. Lepsius then observed (in 1838) that the work of Champollion and that of Mr. Seyffarth, on the papyrus of Turin, were very analogous in the essential points, and similar as to the division into twelve pages or columns. This indication given by Mr. Bunsen is accurate; it would be a difficult enigma for me if the name of Salvolini were not the word that will explain it.[*]

Let us recall at first that the work of restoration of the royal papyrus by Mr. Seyffarth includes several fragments unknown to my brother. They had been hidden from him, but were shown to Mr. Seyffarth, whose opinion of the Egyptian writing system differed in fundamental points from those of the French scholar. Thus, an antagonist was favored by wretched malice, an ordinary resource of petty minds, who serve science only in the interest of their implacable vanity!

When, therefore, Mr. Lepsius lived in Paris in 1838, a copy of the whole royal papyrus of Turin, written in the hand of my brother, divided into twelve columns, and analogous to Mr. Seyffarth’s copy, as Mr. Lepsius had only received the isolated fragments from me, copied by my brother at Turin (no one else knew), he could not have seen Salvolini’s copy.

There is, in fact, among the manuscripts in the hand of Champollion, which were found in the estate of the deceased Salvolini, large format manuscript folios written entirely in the hand of my brother, and entitled: Canon des dynasties égyptiennes: manuscrit hiératique de Turin.

It is a book of twelve sheets in folio; all the united fragments of the papyrus are transcribed thereafter on twelve pages. Each page bears from twenty-five to thirty lines; the lines are of unequal length and are written from right to left, according to the rules of hieratic writing. Each line begins with the group where the bee dominates, which usually precedes every royal cartouche; then comes the cartouche more or less outspread, more or less complete. Immediately afterwards is the indication of the duration of the reign of the king whose name occupies the cartouche, and this duration is expressed in years, months, and days, by the signs and by the figures of the hieratic system. The poor condition of the papyrus has left but a very small number of these chronological indications.

The lines without contain twenty-five to thirty signs. There are still more that do not begin with the group of the bee and with a royal cartouche, and many numerical signs, it has been thought that these lines give the totals of successive dynasties or reigns, numerical summaries absolutely similar to those found in the Greek lists of Manetho.

Champollion says in his letters of 1824 that certain groups are written in red on the original manuscript. In his copy, these signs or groups in red are transcribed by a double stroke in pencil. Such is the state of the twelve pages of this copy, written with a very fine hieratic character, large and bold with an order pleasing to the eye, by the exact vertical correspondence of the two principal lines of each line, the initial group, and the year group that shares it in the middle of its length. Some notes in pencil are written on the margins in the hand of the clever copyist; they were readings of cartouches or attempts to divide the dynasties, and he had not confined himself to these names or notes. Seriously occupied with this precious table of the Egyptian dynasties, he had undertaken the entire translation. Of the first two pages, in French, line-by-line, remains; it was attached to the hieratic text, when Salvolini appropriated it.

It was this manuscript, which Salvolini was obliged to show to Mr. Lepsius, but with odious precaution suppressed the two sheets containing the French translation of the first two pages of the papyrus, written in Champollion’s hand, and substitute two other sheets copied with his own hand, in order to appropriate this rendering. The two autographed sheets of Champollion and the two plagiarized sheets of Salvolini were returned after his death, including the hieratic manuscript (everything is today in the collection of the government). I must stress that I do not lightly accuse a man of the design of taking possession of the labors of another. It will suffice to show what use Salvolini made of the autographed manuscript of his master, too confident in the recommendations that introduced this stranger to us.[*] Salvolini had nothing to do with the restored and beautifully written copy of the papyrus; he attached himself by the two translation sheets of the first two columns. He transcribed them in his poor hand, servilely imitating the distribution of the text of the master, even to the erasures, corrections, interlinear crowding and additions of the original, copying the unnecessary or accidental signs found there, either in the margins or on the written page, thus giving his fully concealed copy the appearance of an autograph and thoughtful work.

I may add other traits by continuing the comparison of the four leaves, but it will suffice to say that Salvolini communicated and allowed publishing under his name this French translation of the first two pages of the papyrus of Turin. They contain the reigns of the gods with their duration; the reigns of Menes and Atothis, the first two kings of the First Dynasty of the Pharaohs, as well as the figures of the various divisions of the chronology of the Egyptian dynasties, according to the general system of these dynasties of gods and men.

It is in the work already quoted by Mr. Bunsen that we can see a textual abridgment of these chronological indications, drawn from the French translation, in which the learned German critic does miss honoring Salvolini, who naturally, had not told the public about the origin of his Egyptian science, at least equal to that of the founder.[*] We shall return later to the manuscript of Champollion and its origin.

Let us add that, to follow the order of the times, according to Mr. Bunsen, Mr. Lepsius noticed an important difference between one of the fragments of my brother and the work attributed to Salvolini. In a passage where he thinks he has found the list of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Pharaohs, so he went back to Turin in 1840 to clarify this problem by examining the original fragment. Two years later, in Berlin 1842, he published four lithographed sheets to the satisfaction of science, his own copy of the entire papyrus, reconstructed and also divided into twelve columns.[*] Each fragment, large or small, which bears some signs of writing, names or numbers only, or which remains blank, its contours are drawn, and numbered according to the place assigned to it in this general representation of the precious manuscript.

The first and second columns of the lithograph contain the figures of the great chronological divisions, the names of the gods, and the first two names of the first dynasty. The third column continues the list of kings and opens with a well-known cartouche, that of a Nephercheres. On the following columns, until the end of the twelfth, the names of kings, and, in unequal spaces, the figures of the reigns succeed each other line by line. The seventh, eighth, and ninth columns are very rich in the names of kings and figures; the last three are less so, and the numerous lacunae are irreparable.

Summarizing the indications hitherto recorded in this brief, we see:

- That there existed an Egyptian manuscript on papyrus in hieratic writing, in pages or columns, written at the latest during the 19th dynasty of the pharaohs, around the twelfth century before the Christian era. It contained a list of the kings of Egypt from the beginning of the monarchy, with the duration of the king’s reign expressed in years, months, and days. The duration of several successive reigns form a dynasty, and the duration of several successive dynasties were expressed by their totals at unequal intervals. This list of the reigns of kings was preceded by a list of the reigns of the gods and a numerical indication of the principal divisions of the Egyptian chronological system. This manuscript was a chronological canon of the kings and dynasties of Egypt, and of an ancient sort by its form of writing and its principal divisions, the same as the Greek work of Manetho.

- That considerable number of fragments of this manuscript exist at the Royal Egyptian Museum at Turin.

- That the greater part of these most important fragments were discovered in the year 1824 by Champollion the younger, who made a copy of it piece by piece, and who exactly qualified them by announcing them at once to the learned world as the remains of a chronological canon of the kings of Egypt.

- That Mr. Seyffarth saw and studied these fragments two years later, in 1826, and found fragments that the French scholar had been prevented from seeing. He tried to restore the manuscript by the combination of fragments, and he composed a total of twelve columns or pages of which he made a copy,[*] of which he has made other.

- That Mr. Lepsius again studied these same fragments at Turin in 1835, and he also made a copy of them, realizing that some of the pieces were missing that were copied by Champollion, eleven years earlier.

- That in 1838 Mr. Lepsius being in Paris, I disclosed to him the copy of the fragments made by Champollion; that in 1840 he again studied the fragments at Turin, and in 1842 he published, by lithography, a facsimile of the whole reconstructed papyrus.

Of this precious and unique manuscript, we know thus far:

- The original fragments, at the Museum of Turin.

- A figurative copy of the most important of these fragments and strays, made by Champollion in 1824.

- A copy made by Mr. Seyffarth in 1826, of all the existing fragments, which he related according to his ideas, and distributed in twelve successive columns.

- A copy of the work of Mr. Seyffarth, made by my brother.

- Another copy made of Mr. Seyffarth’s, by Mr. Dulaurier.

- The one given to the British Museum by Mr. Birch.

- The copy made in 1835, and revised in 1840 by Mr. Lepsius, of all the original fragments, less some that existed in 1824.

- The lithograph of the first page by Mr. Birch.

- The lithograph published in 1842 by Mr. Lepsius in Berlin, which represents all the manuscript text, also divided into twelve columns.

In sum three print copies, made by three people at different times, of these same fragments of the original manuscript of Turin, three secondary copies, and two lithographs. This is all that, so far, has been announced to the public, at least to my knowledge,[*] and if I happened to omit some other copy, extract, or actually existing publication, this omission would be involuntary and of no consequence for the rest of this memoir. It matters not; as there are two subjects important for science:

- The manuscript works of Champollion the younger on the royal canon of Turin.

- The comparison, in the sole interest of the progress of Egyptian studies, of these works with other essays on the same subject, known or published from the year 1824 to the present.

J. J. Champollion-Figeac

Second part, pages 461-472

Coming to the manuscripts of Champollion the younger, relative to the royal papyrus of Turin, we shall first stop at his first copy of the isolated fragments. They are forty-six in number, transcribed on thirty-seven sheets, format in-8° and numbered from A to U. Fragment A contains five names of kings; Fragment B, six names; Fragment C, five names; the fragments D, E, F, G, twelve names, and so on; in all more than one hundred names, complete or incomplete. Each of the original fragments is figured on that copy, with the irregularities of its outline, and if the back contained some writing, the transcription is next to that of the signs on the front of the same fragment.[*] On some there are only written numbers; the fragment Nn forms part of the first column which contain the dynastic gods, followed by the name of king Menes. Others belong to two columns at the same time, showing the characters of one to the left, and of a second on the right, with the beginning of the royal cartouches of the second on the left, and such is the fragment Jj.

Finally, when some sign of a group has suffered in its tracing, like when it is partially erased, the union of the remaining parts is indicated by dots or a fine line, their recovery with only a sense of the group. Nothing has been neglected to give these copies the very value of the original, and the value is great, since it is a historical manuscript in the highest degree, at this time, no less than three thousand years of seniority. This copy of these fragments is a proper depiction. This copy is still the only one that has faithfully observed the deplorable state of the original and its dismemberment. This testimony, it is understood, will be of great interest to science. It must be said, that the reconstruction of the papyri in twelve columns, with the aim of reconstructing the continuation of the reigns of the kings and the succession of the dynasties of Ancient Egypt, has been attempted and executed with more or less happiness and by some archaeological data. From which it inevitably follows that in these reconstructions, as we know them by the copies of the work of Mr. Seyffarth, an inevitable doubt preoccupies the person who studies them. Since the author of this reconstruction very often placed a king as the successor or predecessor of another king only by conjecture, whence it follows that there arises a doubt almost every line of this great work of reconstruction.

On the other hand, with the copies of the fragments these faults diminish drastically, for such copies contain, like the original, five or six names of kings, clearly show that these five or six kings succeeded each other on the throne. These isolated and unpublished copies of each fragment will thus be a new element of criticism, a precious element of a binding relation, and equal to the originals. Not only in the study of Egyptian chronology in general, but also in that of the other royal monuments, especially those which preserve more or less extensive lists of kings of Egypt and the order of their succession. Two names of Pharaohs, discovered singly on temples or stelae, also found on one of the fragments of the royal canon, would immediately establish their incontestable order of succession. With a certain number of similar facts, and some points of connection between the fragments, one would very quickly arrive at certainties on the general list of kings Egypt, even of archaic dynasties.

The copies made by Champollion in 1824 will thus be a means of a certain and indispensable control of all the works made later on the Royal Canon of Turin. Especially those of Mr. Seyffarth, whose conjectural reconstruction of the original papyrus has produced a text of three hundred successive lines, but in which it is impossible for anyone to separate in this work the certainty of conjectures, for these have presided over the classification of the fragments, and time may give them to be in another order. Hence, there is certainty only in the order of succession of the kings written on the same fragment. From one of these kings to another, the order of succession is certain. From one fragment to another, this order is only conjectural, as are also the motifs derived from various probabilities, which have served to determine, in these three hundred lines, the place of each of these fragments hitherto isolated.

The copies of Champollion thus contain, like the original fragments, all the certainties which criticism can adopt on a document of the highest historical interest, a monument of the rarest merit both by its antiquity and by its subject. It is therefore on these copies that the scholars who are interested in this study ought to concentrate. These copies will enlighten them on the mode of reconstruction of the ancient text by Mr. Seyffarth, and on the method adopted by Mr. Lepsius in an undertaking quite analogous to the object, and, as may be said beforehand, by the results.

It is evident from the first examination of the four plates published by Mr. Lepsius in 1842, that he has, as expected, foresaw the reflections which we have just described on the subject of the authority of each isolated fragment, as well as the doubts which arose on their conjectural assembly. Mr. Lepsius therefore divided the reconstruction of the royal canon in columns, and numbered each of the fragments that enter into the composition of this column. In the lithographed sheets, each fragment is a faithful copy of the original, and there is, as in the original, certainty for the succession of names written in each fragment, and there are more than guesses, doubt in short, on the order assigned in each column for the isolated fragments.

Unfortunately, we cannot say that these certainties exist in the work of Lepsius, with regard to the succession of names of kings he included in the same fragment. Because, by comparing the copies of these pieces, as published in his lithographs, with the original copies of Champollion, it is clear that the copies of the same fragments, though made from the same originals by the two learned archaeologists, are not exactly alike.

For example, we see on the first plate of Lepsius, that the first column is formed almost entirely by fragment 1. This fragment present thirteen more or less complete successive lines, but without solution of continuity of the content of the fragment; and the copy of Champollion, on this part of the royal papyrus, reproduces only a much smaller fragment where we find only five of the thirteen lines given by Lepsius. The eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth; about the other eight lines on thirteen seven who have preceded and who would have followed the copy of Champollion, they certainly did not exist at the time of these copies, and the original fragment contained only the five names then transcripts. There is therefore in the copy of fragment 1 of Lepsius, two or more fragments brought together and assembled. Here there is certainty as to the succession of names on each fragment, but the reader know that there is only conjecture in the union of these small portions of a single fragment of thirteen successive lines.

In the third column on the first plate of Lepsius, the first six lines are shown as a single component fragment 18, and in the copies of the French scholar, these six lines are on at least two fragments. Fragment 20 of the same column gives eight names on lines 7–16, while in the copies of 1824, that fragment carries only lines 11 and 12 of the same passage. In the fourth column, fragment 34 has 13 successive lines, from the tenth to the twenty-second, apparently written on a single piece of papyrus. While the copies of Champollion note the existence of at least three fragments, the first bearing the lines 10, 11, 12 of the lithography; the second, lines 13, 14 and 15; and the third, the last four, lines 19, 20, 21 and 22. So there is still a question about this unusual series of thirteen lines resulting from several fragments brought together without interruption. At the seventh column, the first eleven lines also appear to be written on a single fragment, Champollion found two which together only account for six of the eleven lines.

Finally, the ninth column of Lepsius contain twenty-six names, is found entirely (except only one name), in copies of Champollion. However, the lithograph indicates at the beginning of these twenty-six lines, three fragments numbered 97, 98 and 101, while the copies of Champollion show at least six fragments for this same column, and the stitching in the lithograph that has reduced the six fragments to three, are in no way indicated, or visible to the reader. What is certain, is that since 1824 the fragments have not changed shape, they could neither shrink nor grow as an effect of time, rather the opposite was to be expected. If it therefore today shows larger fragments than they were in 1824, it is because these large fragments were composed, with varying degrees of certainty, of several small fragments known before. We have already said above how, for the fruitful study of the Royal Turin papyrus, we needed to be informed.

If we had to demonstrate the application of this remark in quite recent research, we caution that in a special essay,[*] a fragment of the Royal Turin Papyrus is quoted, holding the names of the last two kings of 19th dynasty, the duration of these two reigns and the total duration of that same dynasty. This seems to be after the lithography of Lepsius (col. VII, lines 1, 2, 3), but according to the facsimile of Champollion, these smatterings are scattered over at least three fragments. One that bears the names of two kings, another two lines of numbers and added to the first, and a third containing the total years of a dynasty that Champollion did not know. In the same book,[*] another fragment is quoted (col. VI, no. 63) “which includes, say, six kings and in which the second last of the dynasty (the 6th) is occupied by the cartouche of King Ra-neb-tou”, it is still the lithograph of Lepsius it cites as testimony.

We can see that, six lines later, written on a single fragment, which in copies of Champollion shows only remnants of numbers and names that match only two lines. The second and third largest of the fragment where it has gathered six; still with no stitching shown and on which serious criticism of such texts has the right to be informed, to avoid the expose to hazarded conclusions, because some materials fail being authoritative.

Now, it seems safest to caution readers and to publish the fragments of 1824; it is reproduced, after a new and recent audit (in 1848) of the original papyrus, on the enclosed plate. Adding to that, for the ease of comparisons it will bring, the fragments are ordered in the order Champollion put them in his copy, numbered by the letters of the Latin alphabet, adding a Roman numeral to each Latin letter, to designate the column lithographed by Mr. Lepsius, and where to find the fragments of 1824, quoted on plate 149.

If we compare these isolated copies of the entire tableau published by Lepsius, and reproduces the names according to Mr. Seyffarth reconstruction, we will reap several benefits:

- One cannot consider two or more kings of Egypt named in the papyrus as having succeeded to the crown, until their names are found written in succession of one another on the same original fragment or copy from 1824. Whatever precede or follow the content of this fragment, will have been placed there more or less by conjecture.

- The copies made in 1824 of the primitive state of the papyrus fragments retain signs or traits that have since disappeared, and that kind of indication is never useless.

- Original copies of 1824 are the work of a skilled hand and a mind that counted all the lineaments traced by his own hand. The result is that some passages reproduced by lithography with uncertainty in the drawn signs, or with surcharges, are found firmly copied to the old layers, and so remove any uncertainty about the nature and expression of signs.

- In respect of the number of fragments, in the copies of 1824, there are only forty-six, which cannot be compared with the plates of Lepsius, which reproduce a hundred and sixty-four. It is true that nothing has been forgotten, nothing omitted, and this religion of the fragments is a great testimony of zeal and loyalty, but there are at least forty that are blank or that only have a single sign or a sign portion, and they are actually without use.

In the other hundred and twenty fragments, we do not see a full or nearly full name of a Pharaoh who is found on copies of Champollion; and in these copies, there are also eight fragments that are missing in the lithographed plates of Lepsius. These fragments, still unpublished, give us four names of kings in sets of two. Nine groups dominated by the bee beginnings, plus two sets of figures, a four, the other three lines. Finally another series of six numbers superimposed and written at the back of the first column of the papyrus: the unpublished fragments of the royal canon are reproduced on our plate with the letters Aa Bb Cc Dd Rr Ss Tt Uu. Thus, the copies of Champollion although from 1824 will not arrive too late.

I previously said that my brother had started to transcribe all these fragments in 1824, in a notebook. Without attaching an idea of royal succession, he arranged them according to the letters of the Latin alphabet. This notebook has two columns on each page; the right column depict the cartouche from the hieratic papyrus, while in the other column he added the transcription of these cartridges in hieratic with hieroglyphic characters.[*] He did this work on only twenty to twenty-five cartouches, and did not finish on the fragments. Perhaps he reserved it for the entire papyrus, as rebuilt by Mr. Seyffarth.

This brings us to the complete copy of the papyrus in Champollion’s hand, after the work of Mr. Seyffarth was communicated in 1838 to Mr. Lepsius in Paris, through Salvolini; this copy dates back to the year 1827. The initial idea can be seen above. The difference of opinion on some fundamental points of archaeological doctrines established by the French scholar that manifested itself publicly from 1824 between Mr. Seyffarth and Champollion have not been forgotten. These differences of opinion did not affect the character of the two scholars; as they discussed both verbally and in writing, without thereby moving away from each other; they treated the opinions independently, and each other with respect and courtesy. After meeting in Rome, they soon met again in Paris at the end of 1827, and the first care of Champollion, curator of the Egyptian Museum of the Louvre, was to introduce Mr. Seyffarth and provide him free attendance, with the ability to copy everything that could be of interest. If he did not have complete access, he says in one of his books that this was not the fault of the curator.[*]

For his part, Mr. Seyffarth was no less polite, no less liberal. As was said above, he had copied the fragments of the royal papyrus in Turin. He had brought them together and tried this reconstruction of which we have already spoken; he showed it to Champollion and lent it to him with permission to make a copy, asking him at the same time for a list of the kings of the sixteenth and seventeenth dynasties from the monuments. Here is the text of the letter from Mr. Seyffarth:

Since all I have is available to Mr. Champollion, I see no difficulty to send you my copy of the historic Egyptian manuscript of Turin, and to retain it for a couple days, and copy it as it pleases, etc. I would really like to publish this precious manuscript myself; and with this opportunity, I would ask Mr. Champollion if he will allow me to copy his catalog of the kings of the sixteenth and seventeenth dynasty, found in a temple in Egypt, promising not to make any public use of it. I have the honour to salute Mr. Champollion.

Paris, December 25, 1827.

“SEYFFARTH”

There was an excellent exchange between the two scholars, and we note here is that as a souvenir too rare in the history of science. In the manuscript of Mr. Seyffarth, Champollion found his original copies from Turin, and saw for the first time how the German scientist had been favored, and had had the benefit of adding to it. He made the copy he had permission to make, with some changes. More regularity in the trace of the sometimes uncertain signs, which is the origin of the variants that Mr. Dulaurier noticed between the copy of Champollion that I had disclosed to him, and the work of Mr. Seyffarth, of which he gave a copy to Mr. Birch in London. The latter mentioned these variants in Champollion’s manuscript.

On the pages of this manuscript, there are twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-five, twenty-seven or thirty lines; twelve pages correspond to the twelve column lithographs of Lepsius; the pages are placed in the same order on both copies, and comparing the manuscript with lithographs seems to me to be the more intelligible description. In the manuscript, the first column, which could well be the second,[*] is better preerved and the lines are more complete, at the beginning and at the end. The repeated name of Menes is more evident, and the beginning of one Athothis is very visible; the deficit of lithographs bears particularly on the figures which terminate the first and last lines. The same observations can be made with respect to the second page of the lithograph, although they are less important, this second page of the manuscript has suffered much more than the first. The third page in the manuscript is full. The fourth page is almost identical in both copies, except for the first line, which in the manuscript, is more complete. Concerning the fifth page, there is not a constant ratio in the order and composition of royal names, and the manuscript retains a greater number of numerical signs. The sixth page is damaged in both copies; the manuscript is still more complete here, as to the numerical signs. There is no difference on the seventh page; the same observation on the eighth, adding that the cartouche of the second line, very vague in lithographs, is very distinct in the manuscript. The ninth page is the richest of all in the number of names of kings, that for which there is more information in the copy made in 1824; its influence is recognized by a more regular transcription of some cartouches in the manuscript. The tenth page has large gaps in both copies; there are, however, more lines of numbers in the manuscript that, for the names of kings, are also less damaged in general. The same observations can be made for the eleventh and twelfth pages.

Adding as general remarks, it is clear from these comparisons, namely:

- That there is a great analogy between the copy made by Mr. Seyffarth, the copy transcribed by Champollion and Mr. Lepsius lithographs published following a review of the original fragments.

- In the lithographs, the classification of the fragments is the same as in the work of Mr. Seyffarth.

- There are more numerical data of the reigns in this work than in the lithographs, Mr. Seyffarth having seen the originals when they were less damaged.

- That a copy of Champollion has everything you would find in the work of Mr. Seyffarth and the lithographs of Lepsius, and offer greater sharpness in the traces and in the arrangement of the signs.

- Finally, the merit and archaeological value of the three copies of the reconstruction of the ancient royal papyrus are undoubtedly subordinate to the eminent authority of the original copies, and the isolated fragments, made in 1824 by Champollion. The dynastic arrangement of these fragments with names of kings; those who carry numbers, the assigning of numbered fragments of names within the three copies, a purely speculative operation, and consequently an insufficient authority.

In review of the methodology that led to the restoration of the papyrus by its fragments, we discover without mental effort all the elements, and soon, the thought that inspired all, namely, desire to reconstruct a kind of original Egyptian prototype of the Greek lists of Manetho, by arranging in order of these lists, all known fragments of papyrus. One does not realize that by destroying their true merit; the native merit of these fragments, stripping them of their own value, one has first to protect, preserve and purify them of any modern influence, even at the risk of Manetho. It is true that the decay of the ancient book has greatly reduced the risk. However, even the skill of the architect could still obliterate these materials, and create doubts about their nature, whether by their description or by the feature we have, we can gladly see their original state in copies made by Champollion.

The examination of the reconstructed papyrus inevitably leads to the assumption that the learned German (Mr. Seyffarth), in possession of all remaining original fragments, carefully arranged those with names of kings, those with only numbers. He placed them where possible, in the order in which these names and numbers are stored in the lists of Manetho, providing a series of kings to form a dynasty. Separating this dynasty as follows, born of the same principle, using a fragment bearing numbers; also between several sets of kings forming a series of dynasties by other fragments of numbers giving the total years of several dynasties, as seen in the Greek text of Manetho.

But for such a simple operation, that only operated according to the numbers assigned to each of the reigns dynasty by Manetho, without addressing the general lack of synonymous kings of the Egyptian text compared to the reconstructed Greek text. For such an operation, however, there existed a great difficulty which had to be met beforehand, even arbitrarily resolve, and here it is: “Which list of Manetho will be used as a guide? The longest, if materials abound, or the shorter if they do not?”

In fact, there are plenty, and lists of Eusebius for the first dynasties were preferred to those of Julius Africanus. Menes of the Sixth Dynasty was placed in the reconstructed papyrus of seventy-six kings, Africanus only has forty-three, but Eusebius seventy-three. After a fragment bearing two lines of numbers, just six names are said to be those of the kings of the Sixth Dynasty, composed of that number of kings according to Africanus and Eusebius. After the Twelfth, we find ninety-six lines of kings, and we know that both compilers of Manetho give sixty kings to the Thirteenth and seventy kings to the Fourteenth. There are still about sixty lines of kings in several separate series with numerals. Thus ends the reconstructed papyrus, where we meet the last page with the most mangled fragments.

Thus, in this collection of reconstruction, it is not the old state of the papyrus, whatever it was, of the Egyptian text of a papyrus written around the 12th century BCE, which is being forced into concordance with the text of a Greek writer who lived perhaps ten centuries later. It is very probable that the papyrus and the Greek lists had analogies such that their historical authority is mutually reinforced. I agree that some kings named in both the papyrus and the lists, were able, according to Manetho, to be very well or fairly well placed in the recreated papyrus; but these similarities, which Mr. Seyffarth has carefully sought but not always found, are extremely rare, and have not been able to procure for this laborious reconstruction but a very feeble aid. For example, it recognizes two Nephercheres in the first line of the third page, and the ninth line of the fifth page. There are also two Nephercheres in the lists of Manetho, one in the Second, and the other in the Fifth Dynasty. In the restored papyrus, if the first Nephercheres is placed in the Second Dynasty, the other is in the Fifth according to Manetho, is recorded in the Third in the papyrus, after Nitocris which is thus in the Third according to the papyrus, but actually in the Sixth according to Manetho, this arrangement does not make sense.

Through these considerations, I do not mean to deny the importance, although undeniable to everyone, the venerable remains of the ancient papyrus, nor weaken the merit of the work of the two learned Germans whom I have already named. I can only propose to appreciate, for myself at least, the degree of certainty of the facts these remains reveal to us. This certainty appears complete to me, regarding the names, these fragments preserve, and to the dynastic succession, these tell us about. Also for the reconstruction of the same papyrus, which is the result of research by Mr Seyffarth adopted by Lepsius, is the time to bring to light the sagacity and happiness of these two archaeologists.

There is already a great value to report in favor of the work of Mr. Seyffarth, to have furnished Champollion with the occasion of some special research on this matter; because of the copy of his work, he had in fact, added some notes and some translations: let us enter upon this subject in some detail.[*]

J. J. Champollion-Figeac

PLATE 149.

after the fragments copied in 1824 by Champollion the younger.

*Discorsi critici, by Mr. Barucchi ; Turin, 1844, 4. –Ägyptens stelle, etc., by Mr. Bunsen; Hamburg, 1845, 3 vol. in-8°. –Annales de Philosophie chrétienne, article by Mr. de Rougé. – Nouvelle Revue Encyclopédique, published by Firmin Didot, June 1846, p. 222 ; December, p. 615, etc.

*Section 7, Vol. 2, 1824, cahier de novembre, article n° 292. [Champollion. “Papyrus Égyptien”, Bulletin des sciences historiques, antiquités, philologie 2, (Paris 1824), Art. no. 292, pp. 297–303.]

*On the back of the Royal canon are accounts with the name of a Rameses of the 19th dynasty.

*Discorsi, p. 21 and 30 [transl. “the papyrus is at present reduced to many minute fragments”]

*I Monumenti, etc., Vol. 1, p. 146. The duration of the reign is not the date.

*Observations upon the hieratical canon of Egyptian Kings at Turin 6-page pamphlet (undated). [later printed in Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature, Ser. 2, Vol. 1, London 1843, 203–208, facsimile not present.]

*Observations by Mr. Birch, p. 2.

*See my Notice des Manuscrits de Champollion le Jeune perdus en 1832 et retrouvés en 1840. Paris: Didot, 1842, 8-page pamphlet.

*Salvolini came to my brother, by first writing him a long letter of four pages in folio, in which he expressed the intention of engaging in Egyptian archeology, etc., and asks for a job which will make him subsist. He soon presented himself with letters of recommendation from his compatriots and friends Messrs. Orioli, Gazzera, Peyron, Rosellini, maestro Rossini and others.

*We read in the textual quotation made by Mr. Bunsen, after Salvolini, p. 84, the numbers 5613, 23200 and 13420, instead of 5623, 24200 and 14420, found in the original translation and in the copy by Salvolini.

*Die Turiner Königs-annalen, publicieren von R. Lepsius, Berlin, 1842; 4 sheets, lg. folio in-plano. I am indebted to the kindness of Professor Baracchi of Turin for the copy I have of the four plates lithographed by Mr. Lepsius.

*I omit here the deliberate and deplorable part of Salvolini on this account, the death of my brother having taken place in 1832.

*This was written in 1847; an addition to the memorandum of Mr. J. B. G. Lesueur, published later, will be found below.

*It is common to find on the back of a papyrus sheet more recent texts than those on the front, as the scarcity of papyrus in Egypt had commanded this economy.

*Examination of the work of Mr. Bunsen, by M. de Rougé, p. 18. Extract from the Annales de Philosophie chrétienne (Annals of Christian Philosophy.)

*ibid, p. 13.

*This notebook is also in the collection of government.

*Under the pretext of a plan to publish the Egyptian Museum, Mr. Seyffarth was rather sharply, but officially dismissed from the Egyptian rooms of the Louvre.

*This column ends with the first two names of the kings of the first dynasty, Menes and Athothis. The other names of kings follow, and this column, considered as the second, would be perfectly connected with the third, in which the series of kings of the following dynasties is immediately continued. The text of the second and third columns seems to unite them naturally and necessarily. It follows that the column considered by Mr. Seyffarth to be the second, is very irregularly placed between the two which we have just designated. For this second column of Mr. Seyffarth, which gives the reigns of the gods, interrupts the list of the reigns of men, which was immediately upon the two pillars already brought together by their very text. I have often thought that these columns one and two according to Mr. Seyffarth, which also indicate the reigns of the gods, also end with the names of Menes and Athothis, may well be the first page of two different manuscripts on the same subject. Examination of the original fragments may decide, but I have not seen them, and my brother having known only one of the two fragments, could not verify, nor thought to verify the similarity or the dissimilarity of the characters of these two initial pages.

*The two remaining articles dives into the content of the papyrus, which is of little interest, and thus omitted.