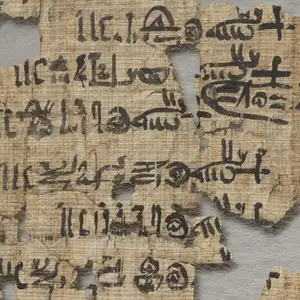

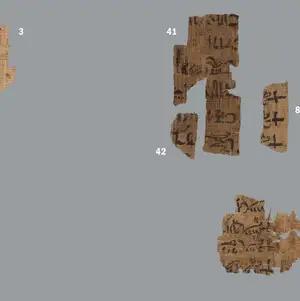

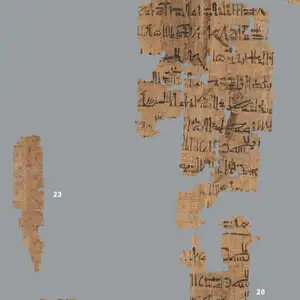

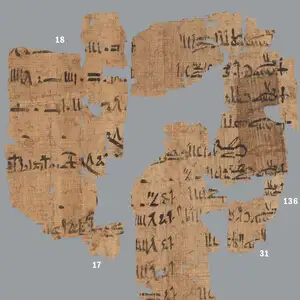

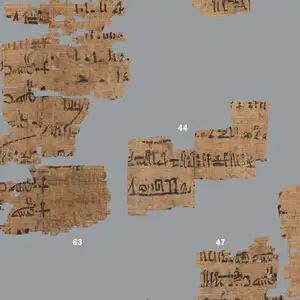

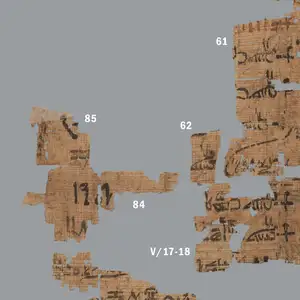

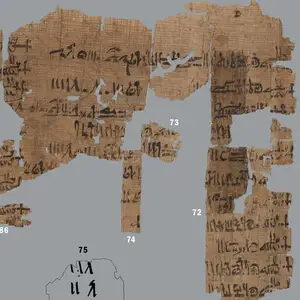

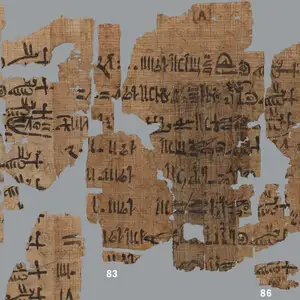

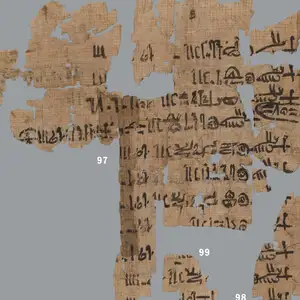

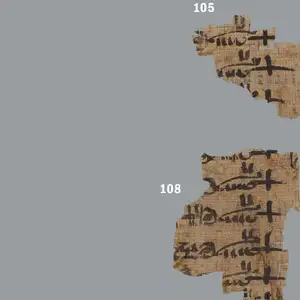

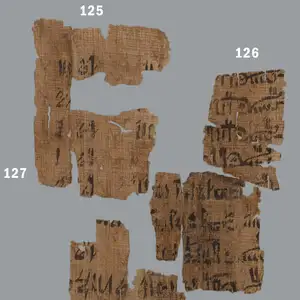

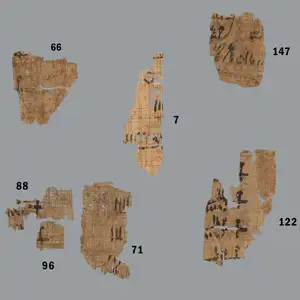

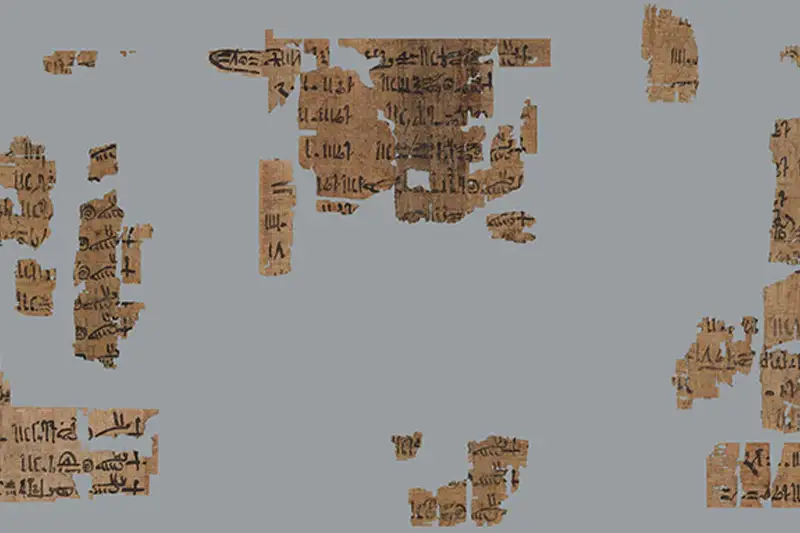

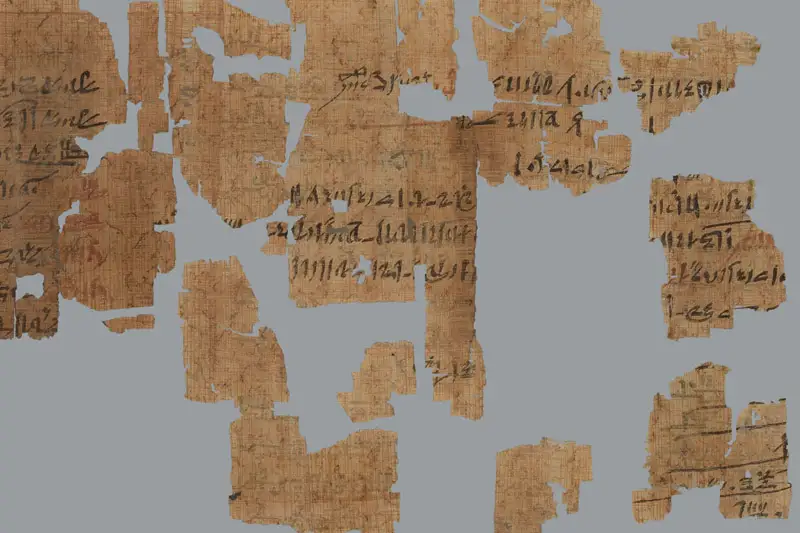

The most comprehensive ancient list of Egyptian pharaohs can be found in the so-called Royal Canon of Turin, a poorly preserved hieratic papyrus roll from the reign of Ramesses II. It is also known as the Turin King List, and is without a doubt the most significant king list of Ancient Egypt and was uncovered in 1824 by Jean-Francois Champollion in the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy. Two-thirds of the papyrus is lost, having been broken into hundreds of tiny pieces during handling and transport to Italy after its discovery around 1820.

The papyrus underwent a modern reconstruction in the summer of 2022, with only minor adjustmentsa and additions made as most of the fragments are already in the correct positions. As of February 2024, no publication of the reconstruction has yet been announced. We have waited for decades, so a few months or years more is nothing...