Obelisks (from Ancient Greek

One of the most sacred sites in ancient Egypt was Heliopolis (

In Upper Egypt, the corresponding site was Heliopolis of the South, i.e. Thebes, the city of the god Amun. Queen Hatshepsut's obelisk in the Great Temple at Karnak is the largest in Egypt. Only about 30 large obelisks from ancient Egypt with hieroglyphic writing still exist. Some of these are reconstructed from fragments and not entirely complete.

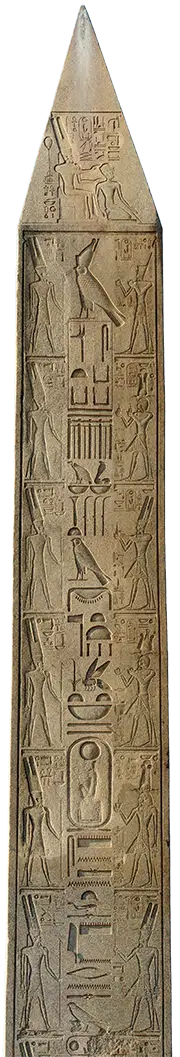

Karnak obelisk D

When renowned traveler Richard Pococke visited Karnak in the late 1730s, both obelisks of Thutmose I were still standing. However, the northern obelisk must have toppled before 1800 and today only the southern of the pair remain standing. It is leaning slightly. Originally created by Thutmose I, it was inscribed with a single column along all four sides of the obelisk. Three centuries later, Ramesses IV had columns added on both sides of the center columns. These added columns were in turn usurped by Ramesses VI only a few years later.

Rosellini 1832. I Monumenti dell’ Egitto e della Nubia, IV, plate XXX

Champollion 1845. Monuments de l'Égypte et Nubie, IV, plates CCCXII-CCCXIII

Lepsius 1849. Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, III, plate 6

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, II, p. 75

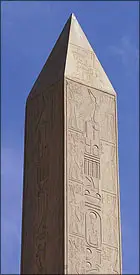

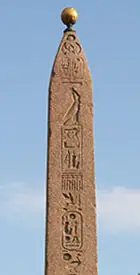

Karnak obelisk E

Of the four obelisks that Hatshepsut erected at the Great Temple complex at Karnak, only one remains in its original location 3,500 years later. It is the tallest obelisk in Egypt; its southern twin toppled and broke apart at an unknown time. Erected for Hatshepsut's jubilee, the pair of red granite obelisks (E and F) were 29.5 metres high. Despite Hatshepsut's successors systematically erasing her name from most of the monuments and temples she had built, these obelisks survived. Due to the almost impossible task of removing two huge obelisks without damaging the surrounding structures, hiding them behind false walls inside the new temple built by Thutmose III was probably an easy solution, rendering the obelisks invisible. The fate of the other pair of her obelisks is unknown; they were probably toppled by one of her successors.

In 2022, the top part of the fallen Obelisk F (11 m., 36 ft tall) was re-erected next to the Sacred Lake at the side of the Great Temple, where it had lain on its side for decades. This is not the obelisk's original position, but at least it is in line with its twin.

Lepsius, Karl Richard. Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, III, plates 22-24

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, II, p. 81-82

Rosellini. 1832. I Monumenti dell’ Egitto e della Nubia, IV, plates XXXI to XXXIV

Breasted, James Henry. 1906. Ancient Records of Egypt, II, §304ff

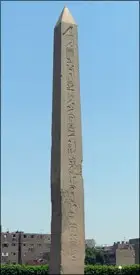

Luxor obelisk A

The Luxor Temple was originally built by Amenhotep III, but about a century later Ramesses II added his own temple–right before it. As was usual, the entrance was dominated by two obelisks at either side of the large entrance to the temple. Both obelisks were given to France as a gift in 1830 by the Egyptian government. The right (western) obelisk was removed and transported to Paris in 1831 at great cost, which deterred removal of the other. The remaining obelisk is still standing in its original location to the left (east) of the first pylon entrance. France formally relinquished ownership of this obelisk in 1981.

Champollion. 1845. Monuments de l'Égypte et Nubie, IV, plates CCCXX-CCCXXI (320-321)

Rosellini. 1832. I Monumenti dell'Egitto e della Nubia, IV.1, plate CXVII B (117 B)

Description de l'Égypte. 1809. Antiquités - Planches, Vol. III, plates 1-12

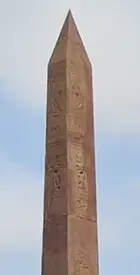

Luxor obelisk B

Originally standing to the right (west) of the entrance pylon to Ramesses II's temple at Luxor. The obelisks were gifted to France in 1830 by the Egyptian government and transport to Paris began the following year. After a long and slow voyage to Paris, it arrived in 1833, and was erected on a large pedestal base in 1836 at the center of Place de la Concorde. The transport was extremely expensive for the time which is probably the reason that its twin still remain at Luxor. The gold-leafed pyramidion was added in 1998.

Champollion 1845. Monuments de l'Égypte et Nubie, IV, plates CCCXVIII-CCCXIX

Rosellini 1832. I Monumenti dell’ Egitto e della Nubia, IV.1, plate CXVII A

Description de l'Égypte. 1809. Antiquités - Planches, Vol. III, plate 12

Lebas 1839. L'obelisque de Luxor: histoire de sa translation à Paris, plate III

Heliopolis obelisk

It's incredible that this obelisk, which was erected by Senusret I over 4000 years ago, is still standing in its original location in Heliopolis. The Romans plundered several obelisks from the site, and probably left the rest in ruins. Today, this obelisk is all that remains of Heliopolis, the medieval expansion of Cairo all but erased the last traces of the once great place. The obelisk was in danger of toppling in the early 1950s due to rising groundwater levels, but was stabilized. A further stabilizing structure was built in the mid-70s, raising the base by 2 meters.

Lepsius, Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, II, plate 118h

Porter & Moss. Topographical Bibliography, IV, p. 60

Crocodilopolis obelisk

Found toppled and broken in two in a field near the ruins of ancient Crocodilopolis by Napoleon's expedition in 1798. The obelisk is erected in the middle of a roundabout in the city of Faiyum. The inscriptions are in very poor shape, only faint traces remain today, and the bottom is cluttered with modern arabic grafitto. It is only thanks to early Egyptologists that the contents of the inscriptions are preserved. Its shape is unique, it is more like a tall slender stela than an obelisk, with no pyramidion but rather a rounded top.

Burton, 1825. Excerpta hieroglyphica, plate XXIX

Rosellini, 1832. I Monumenti dell’ Egitto e della Nubia, IV.1, plate XXV (2)

Lepsius, 1849. Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, II, plate 119, Text II, p. 31

Porter & Moss. Topographical Bibliography, IV, p. 99

Tanis obelisk A

Originally discovered broken at Tanis, it was reconstructed from several fragments and erected on top of a pedestal building at Cairo airport in 1984.

Petrie, Tanis, I, plate VIII (48, North Obelisk)

Tanis obelisk B

Discovered in bad shape at Tanis, it was reconstructed from several blocks in the late 1950s and erected in a small garden on Gezira Island near the Cairo Tower in 1960. It was relocated in 2019 and mounted on a new base in a small square in front the Presidential palace entrance in the new city of El Alamein on the Mediterranean coast.

Petrie, 1883. Tanis, I, plate IX (51, North Obelisk)

Cleopatra's Needle

Erected in Heliopolis by Thutmose III around 1450 BC. Ramesses II had his inscriptions added on either side of the original inscription some 200 years later. It was moved to Alexandria by the Romans in 12 BC together with its twin, where it toppled sometime during the next centuries and slowlyh became partially buried. This helped preserve the hieroglyphs from the effects of weathering. The name Cleopatra's Needle originates from the French nickname it acquired in Alexandria. It was given to Britain as a gift in 1819 but it remained in Alexandria for almost 60 years. Finally, in 1877, it was transported to London and erected in its current position on the Victoria Embankment the following year. The English weather has not been kind to the hieroglyphs which have faded significantly.

Champollion, 1845. Monuments de l'Egypte, IV, plates 445-446

Kitchen, 1979. Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 478-479, §183 A

Cleopatra's Needle

Erected in Heliopolis by Thutmose III around 1450 BC. Ramesses II had his inscriptions added on either side of the original inscription some 200 years later. It was moved to Alexandria by the Romans in 12 BC where it still stood until given as a gift to the US. It was placed in Central Park in New York, and the weather has not been kind to the hieroglyphs. It was erected in its current position in 1881. The name Cleopatra's Needle originates from the French nickname (Les aiguilles de Cléopâtre) it acquired in Alexandria. This obelisk has been standing since antiquity, unlike its (now in London) twin that toppled at an unknown time.

Norden. 1755. Voyage d’Egypte et de Nubie, pls. 7-9

Description de l’Égypte. 1809. Vol. V, plate 32-33

Champollion. 1844. Monuments de l'Egypte, IV, plate 444

Kitchen, 1979. Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 480-481, §183 B

Theodosius obelisk

A pair of obelisks were originally erected south of the Seventh pylon at Karnak celebrating the jubilee of Thutmose III. One of them was brought to Alexandria on orders of the Roman emperor Constantine in the 330s, with plans to bring it to his new capital of Constantinople. The twin was left in place at the temple, where fragments have been found. When Constantine died in 337, the transport was put on hold and the obelisk was abandoned ashore.

Decades later, it is unknown exatly when, it was transported to Constantinople, where emperor Theodosius had a pedestal base with Latin and Greek inscriptions installed. The obelisk was originally about 29 meters tall, but has lost about a third of its lower end. The Latin text alludes to a failed attempt to erect the obelisk, which could account for the obelisk's bottom third being removed. This lower part (now lost) once stood in the Strategium forum complex, according to Byzantine sources, while the upper part was erected in the Hippodrome in 390.

Sepibus, 1678. “Romani Collegii Societas Jesu Musæum Celeberrimum”. Amsterdam.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 400

Durham obelisk

It was discovered in 1838, in the ruins of a village near Thebes, and was presented to Algernon, fourth Duke of Northumberland, in 1838. Only slightly over 2 meters tall, it is on show at the Durham Oriental Museum.

Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature, 1843, I, p. 170.

Philae obelisk

The pair of obelisks, originally from the temple of Isis at Philae, were discovered in 1815 by J. W. Bankes. One is intact, while the other is broken. They arrived at his estate in Dorset in 1821 and remain there today. The sides of the obelisks display a hieroglyphic text, while the base bears a Greek text. While the texts are not identical, they depict the same subject matter.

Budge, E. A. Wallis., 1904. The decrees of Memphis and Canopus, Vol. I, pp. 135-159

Porter & Moss., 1939. Topographical Bibliography, VI, p. 214 (73-74)

Lateranense obelisk

Thutmose III had two obelisks commissioned for the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak, one for himself and another for his father Thutmose II, but before they were completed he died. They were left lying for 35 years, when Thutmose III's grandson Thutmose IV had one erected to the east of the Great Temple. Both obelisks were ordered to be brought to Alexandria on orders of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great in the 330s, with plans to bring them to his new capital of Constantinople. When he died in 337, their transport was indefinitely delayed and the obelisks were abandoned on the beach. In the late 350s, emperor Constantius II ordered the largest of the two obelisks to be brought to Rome in time to celebrate his 20 years on the throne in 357, the other was left on the beach (see Theodosius obelisk above). The obelisk was erected in the Circus Maximus, as companion to the one put there more than 300 years earlier by emperor Augustus. It is the largest and tallest Egyptian obelisk.

Ammianus Marcellinus, Rerum Gestarum, Liber XVII, 4.1-23

Breasted, James Henry. 1906. Ancient Records of Egypt, II, §626-628, §830-838 (translations)

Sepibus, Romani Collegii Societas Jesu Musæum Celeberrimum. Amsterdam 1678.

Habachi. 1977. Obelisks of Egypt. 112-119

Flaminio obelisk

Originally from Heliopolis, it was commissioned by Seti I but only completed and erected by his son, Ramesses II. The hieroglyphs of Merenptah, son of Ramesses II, are also present at the bottom. Emperor Augustus had it brought to Rome together with the Solare obelisk in 10 BC, which is not its mate.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 409 (2)

Kitchen, “Ramesside Inscriptions“, I, 118-120, §58; II, 476-478, §182

Solare obelisk

Originally from Heliopolis, Emperor Augustus had it brought to Rome together with the Flaminian obelisk in 10 BC, where it was erected at Circus Maximus.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 411 (6)

Macuteo obelisk

Originally a pair with Matteiano in Heliopolis. Most of this obelisk remains while its twin has fared much worse.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 409 (3)

Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 481-482, §184 A

Minerveo obelisk

Originally from Sais, it is the mate of the Urbino obelisk. Brought to Rome by Emperor Diocletian, but was buried at an unknown time. Rediscovered in 1665, the pedestal with an elephant was probably added in the late 1660s.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 411 (7)

Agonalis obelisk

Commissioned from Egypt by Domitian and erected in Rome c. 80 AD, the inscriptions are of inferior Roman manufacture. It was moved to Circus Maxentius around 310, where it later toppled into five pieces. It was rediscovered and re-erected in 1651 in its current location — on top of the fountain of the Four rivers.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 411 (8)

Sallustiano obelisk

A smaller copy of the Flaminian obelisk commissioned by Lucius Domitius Aurelianus around 270 AD. It stands at the top of the Spanish steps in Rome.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, VII, p. 412 (10)

Pinciano obelisk

Erected by Roman Emperor Hadrian in Tivoli just east of Rome, supposedly for the tomb of his favorite Antinous around 131 AD. Moved to Rome around 220 AD.

Zoega, De origine et usu obeliscorum, pp.77-79. Rome 1797. Foldout plate in back.

Dogali obelisk

Originally from Heliopolis, it i the mate of the Boboli obelisk. Since 1924 it commemorates the Battle of Dogali.

Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 483, §183 C

Matteiano obelisk

Originally a pair with Macuteo in Heliopolis. This is much shorter, having lost much of its height after a collapse in ancient times.

Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 482, §183 B

Boboli obelisk

Found around 1600 by the Isis temple ruins. A copy was made in the 19th century and was erected at the Villa Medici in Rome.

Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 483-484, §183 D

Benevento obelisk

Erected by the Roman emperor Domitianus at the Temple of Isis in Benevento. The pair are both in the same city.

Erman, A. "Die Obelisken der Kaiserzeit" Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 34 (1896), pp. 149-158, pl. 8

Luxor Museum obelisk

Discovered at the Great Temple of Karnak in 1923, the bottom half has been lost. This small obelisk is on display at the Luxor Museum in Egypt.

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography, II, 184.

Seti II obelisk

The remains of the southern obselisk stand by the row of sphinxes at the quay of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak. Only the pedestal of its (north) mate remains.

Schwaller de Lubicz, The Temples of Karnak, II, plate 7

Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, IV, 250:12-16

Hermopolis obelisk

Fragments that were part of a pair of obelisks, probably originally about 5.5 m high. Now in the British Museum.

Description de l'Égypte, V, plates 22-23

Athribis obelisk

Originally from Athribis in the Nile delta, it was bought and transfered to Berlin in 1895. On loan to Poznan Archeological Museum from 2002.

Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, II, 465-466; IV, 244-245

Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, Inv. # 12800

Urbino obelisk

Originally erected at Sais, it is the mate of Minerveo in Rome. It stands in Urbino, the birth place of Pope Clement XI, who bequeated it to the town.

Abu Simbel obelisks

Originally found in the North Chapel of Ra-Horakhty (Sun chapel) on the right side of the of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel. It is now in the Nubia Museum in Assuan.

Kuentz, "Obélisques", 45-50, plate XIII

Cairo Museum JE 42955 C (CG 17023 & 17024)

Tanis obelisk C

Tahrir Square was redeveloped in 2020 and an obelisk added at its center. This obelisk was reconstructed from several pieces of broken obelisk fragments from Tanis.

Petrie, Tanis, I, plate VII (46, North Obelisk)